Odisha State Board Plus Two First Year Sanskrit Optional Solutions Chapter 4 ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିକଥା Textbook Exercise Questions and Answers.

Plus Two First Year Sanskrit Optional Chapter 4 ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିକଥା Question Answer

अतिसंक्षेपेण उत्तरं लिखत

(क) बन्धनीमध्यात् शुद्धम् उत्तरं चित्वा लिखत-

Question 1.

कस्मिंश्चिन्नगरे ___________________ नाम भूपतिः प्रतिवसति स्म। (विक्रमः, चन्द्र:, सूर्यः)

Answer:

चन्द्र:

Question 2.

तस्मिन् राजगृहे लघुकुमारवाहनयोग्यं ___________________ अस्ति। (गजयूथम्, हयय्थम्, मेषयुथम्)

Answer:

मेषयुथम्

Question 3.

मेषः ___________________ प्रविशति। (मन्दिरे, गृहे, महानसे)

Answer:

महानसे

Question 4.

मेषसूपकारकलहोऽयं ___________________ क्षयाय भविष्यति। (मेषाणां, वानराणां, नराणां)

Answer:

वानराणां

Question 5.

___________________ प्रचुरः अयं मेषः। (उणी, केशा, दन्ता)

Answer:

उणी

Question 6.

अयं मेषः स्वल्पेनापि ___________________ प्रज्वलिष्यति। (वारिणा वायुना, वह्निना)

Answer:

वह्निना

Question 7.

___________________ अश्वानां बह्रिदाहदोष: प्रशाम्यति। (गजवसया, वानरवसया, मृगवसया)

Answer:

वानरवसया

Question 8.

वानरवसया ___________________ वह्निदाहदोषः प्रशाम्यति। (अश्वानां, मूषिकाणां मृगाणां)

Answer:

अश्वानां

Question 9.

मदोद्धताः वानराः ___________________ गन्तुं न इच्छन्ति। (वृक्षं, वनं, गृहं)

Answer:

वनं

Question 10.

जाज्जन्यमान शरीर: मेष: ___________________ प्रलुठतः। (जले, शय्यायां, क्षितौ)

Answer:

क्षितौ

Question 11.

तस्य अश्रद्धेयं श्रुत्वा मदोद्धता वानराः प्रहस्य प्रोचुः। (वदनम्, रोदनम्, वचनम्)

Answer:

वचनम्

Question 12.

ते धन्याः ये कुलक्षयं न पश्यन्ति। (उरुभनं, देशभङ्गं, केशभनं)

Answer:

देशभङ्गं

Question 13.

वानरयूथपः कुलक्षयं ज्ञात्वा परं उपागतः। (हर्षम्, विषादम्, प्रसादम्)

Answer:

विषादम्

Question 14.

भ्रमता वृद्धवानरेण समासादितम्। (मन्दिर:, समुद्र:, सरः)

Answer:

सरः

Question 15.

नूनमंत्र ___________________ दुष्टग्राह्येण भाव्यम्। (स्थलान्ते, जलान्ते, जनपदान्ते)

Answer:

जलान्ते

Question 16.

वानरः ___________________ जलं पिवति। (पात्रेण, हस्तेन, नालेन)

Answer:

नालेन

Question 17.

जलमध्यात् ___________________ निष्क्रमति। (देव, राक्षसः, मानवः)

Answer:

राक्षसः

Question 18.

अत्र यः सलिले ___________________ करोति स मे भक्ष्यः। (प्रवेशं, निवेशं, स्नानं)

Answer:

प्रवेशं

Question 19.

राक्षस: ___________________ अधारयत्। (कुण्डलम्, मुकुटम्, रत्नमाला)

Answer:

रत्नमाला

Question 20.

बाह्यतः ___________________ मां दूषयति। (सर्प, व्याघ्रः, शृगालः)

Answer:

शृगालः

Question 21.

अस्ति कुत्रचिदरण्ये गुप्ततरं महत्सरो ___________________। (धनदनिर्मितम्, वरदानिर्मितम्, शारदानिर्मितम्)

Answer:

धनदनिर्मितम्

Question 22.

तत्र सूर्येऽर्धेदिते ___________________ य: निमज्जति स रत्नमालाभूषितकण्ठो निःसरति। (चन्द्रवासरे, रविवासरे, शुक्रवासरे)

Answer:

रविवासरे

Question 23.

वानरोऽपि राज्ञा दोलादिरूदेन ___________________ आरोपितः सुखेन आनीयते। (स्वोत्सङ्ग, स्वस्कन्ध, दुरश्वेन)

Answer:

स्वोत्सङ्ग

Question 24.

अस्ति मे भूपतिना सहात्यन्तं ___________________। (मित्रताम्, वैरम्, द्वेषम्)

Answer:

वैरम्

Question 25.

रत्नमालादीप्त्या ___________________ अपि तिरस्करोति। (चन्द्रम्, पृथिवीम्, सूर्यम्)

Answer:

सूर्यम्

Question 26.

वानर: ___________________ समये राजानमुवाच। (प्रभात, प्रत्युष, सायं)

Answer:

प्रत्युष

Question 27.

राज्यस्थ ___________________ ईहते। (धनम्, जनम्, स्वर्गम्)

Answer:

स्वर्गम्

Question 28.

अर्धोदिते सूर्येऽत्र प्रविष्टानां ___________________भवति। (बृद्धि:, सिद्धि:, समृद्धिः)

Answer:

सिद्धि:

Question 29.

कृते ___________________ कुर्यात्। (अनुवृत्तिं, निवृतिं, प्रतिकृतिं)

Answer:

प्रतिकृतिं

Question 30.

दुष्टे ___________________ समाचरेत्। (शिष्टं, दुष्टं, रुष्टं)

Answer:

दुष्टं

Question 31.

राजा शोकाविष्टः ___________________ एकाकी यथायातमार्गेण निष्क्रान्तः। (वसति:, ददाति, पदाति:)

Answer:

पदाति:

Question 32.

नानास्वादितं तोयं साधु भो ___________________। (हटनागर, वटवानर, तटशूकर)

Answer:

वटवानर

(ख) अतिसंक्षेपेण उत्तरं लिखत-

Question 1.

कस्मिंश्चिन्नगरे कः नाम भूपतिः प्रतिवसति स्म?

Answer:

ଚନ୍ଦ୍ର

Question 2.

भूपतेः चन्द्रस्य पुत्राः कीदृशक्रीड़ारता आसन्?

Answer:

ବାନରକ୍ରୀଡ଼ାପ୍ରିୟ

Question 3.

तस्मिन् राजगृहे लघुकुमारबाहनयोग्यं किम् अस्ति?

Answer:

ମେଣ୍ଢାପଲଟିଏ

Question 4.

मेष: निःशङ्कं कुत्र प्रविश्य यत् पश्यति तत्सर्वं भक्षयति?

Answer:

ରୋଷେଇଘରେ

Question 5.

के मेषान् ताड़यन्ति?

Answer:

ରୋଷେୟାମାନେ

Question 6.

मेषसूपकारकलहोऽयं केषां क्षयाय भविष्यति?

Answer:

ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର

Question 7.

यदि वस्तुनोऽभावात् कदाचिदुल्मुकेन ताड़यिष्यन्ति तदेर्णोप्रचुरोऽयं कः स्वल्पेनापि वह्निना प्रज्वलिष्यति?

Answer:

ମେଣ୍ଢାଟି

Question 8.

अश्वकुटी कस्य हेतोः ज्वलिष्यति?

Answer:

ପ୍ରଚୁର ତୃଣହେତୁ

Question 9.

कया अश्वानां वह्निदाहदोषः प्रशाम्यति?

Answer:

ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ଚର୍ବି ବା ମଜ୍ଜାଦ୍ଵାରା

Question 10.

वानरवसया अश्वानां कः प्रशाम्यति?

Answer:

ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହଦୋଷ

Question 11.

एवं निश्चित्य सर्वान् कान् आहूय यूथपतिः रहसि प्रोवाच?

Answer:

ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ

Question 12.

कलहन्तानि कानि?

Answer:

ବଡ଼ ବଡ଼ ଗୃହମାନ

Question 13.

कुवाकयान्तं च किम्?

Answer:

ବନ୍ଧୁତା

Question 14.

भवतो वृद्धभावात् किं संजातम्?

Answer:

ବୁଦ୍ଧି ବିଭ୍ରାଟ

Question 15.

नित्यशः का स्रवति?

Answer:

ଲାଳ

Question 16.

तान् वानरान् परित्यज्य स यूथाधिपः कुत्र गतः?

Answer:

ବନକୁ

Question 17.

राजा तदाकर्ण्य कम् आदिष्टवान्?

Answer:

ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରଙ୍କୁ ବଧ କରିବାକୁ

Question 18.

राजा सविषादः कान् आहूतवान्?

Answer:

ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରନିଦାନ ଜାଣିଥିବା ବୈଦ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କୁ

Question 19.

वानरयूथपः ज्ञातिक्षयं ज्ञात्वा परं कम् उपागतः?

Answer:

ବିଷାଦଭାବକୁ

Question 20.

भ्रमता वृद्धवानरेण कीदृशं सरः समासादितम्?

Answer:

ପଦ୍ମଲତାମଣ୍ଡିତ

Question 21.

केषां पदपङ्क्ति प्रवेशोऽस्ति?

Answer:

ମନୁଷ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କର

Question 22.

मनुष्याणां पदपङ्क्ति प्रवेशोऽस्ति न किम्?

Answer:

ବାହାରି ଆସିବାର

Question 23.

नूनमत्र जलान्ते केन भाव्यम्?

Answer:

ଦୁଷ୍ଟଗ୍ରାହ୍ୟ ବା କୁମ୍ଭୀରଟିଏ

Question 24.

किम् आदाय दूरस्थोऽपि जलं पिवामि?

Answer:

ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ଟିଏ

Question 25.

जलमध्यात् कः निष्क्रान्तः?

Answer:

ରାକ୍ଷସ

Question 26.

कीदृश: राक्षस: जलमध्यात् निष्क्रान्तः?

Answer:

ରତ୍ନମାଳାରେ ବିଭୂଷିତ କଣ୍ଠବିଶିଷ୍ଟ

Question 27.

अत्र सलिले यः प्रवेशं करोति स मे कः?

Answer:

ଖାଦ୍ୟ

Question 28.

अस्ति मे भूपतिना सहात्यन्तं किम्?

Answer:

ଶତ୍ରୁତା

Question 29.

तं भूपतिं केन लोभयित्वात्र सरसि प्रवेशयामि?

Answer:

ବାକ୍ତୁରୀଦ୍ୱାରା

Question 30.

का दीप्त्या सूर्यमपि तिरस्करोति?

Answer:

ରତ୍ନମାଳା

Question 31.

रत्नमाला दीप्त्या कमपि तिरस्करोति?

Answer:

ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟଙ୍କୁ

Question 32.

क्वापि कीदृशं सरोऽस्ति?

Answer:

ରତ୍ନମାଳା ଥିବା

Question 33.

भूपतिना सह रत्नमालालोभेन सर्बे के प्रस्थिता:?

Answer:

ସ୍ତ୍ରୀ ଓ ଚାକରମାନେ

Question 34.

शती किम् इच्छति?

Answer:

ହଜାରେ ମୁଦ୍ରା

Question 35.

कस्य केशाः जीर्यन्ते?

Answer:

ଜରାଗ୍ରସ୍ତ ବ୍ୟକ୍ତିର

Question 36.

एका का तरुणायते?

Answer:

ତୃଷ୍ଣା

Question 37.

तत्सरः समासाद्य वानरः कदा राजानमुवाच?

Answer:

ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୁଷକାଳରେ

Question 38.

अथ प्रविष्टास्ते लोकाः सर्वे केन भक्षिता:?

Answer:

ରାକ୍ଷସଦ୍ବାରା

Question 39.

वानरः सत्वरं कम् आरुह्य राजानमुवाच?

Answer:

ବୃକ୍ଷକୁ

Question 40.

हिंसिते किं कुर्यात्?

Answer:

ପ୍ରତିହିଂସା

(ग) उत्कलभाषया अनुवादं कुरुत-

Question 1.

कस्मिंश्चिन्नगरे चन्द्रो नाम भूपतिः प्रतिवसति स्म।

Answer:

କୌଣସି ଏକ ନଗରରେ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ର ନାମକ ରାଜା ବାସ କରୁଥିଲେ ।

Question 2.

अथ तस्मिन् राजगृहे लघुकुमारवाहनयोग्यं मेषयूथमस्ति।

Answer:

ସେହି ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦରେ ଛୋଟରାଜକୁମାରମାନଙ୍କର ବାହନଯୋଗ୍ୟ ମେଣ୍ଢାପଲଟିଏ ଥିଲା ।

Question 3.

सोऽपि वानरयूथपस्तद् दृष्ट्वा व्यचिन्तयत्।

Answer:

ସେ ବାନର ଦଳପତି ମଧ୍ୟ ତାହା ଦେଖ୍ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା ।

Question 4.

मेषसूपकारकलहोऽयं वानराणां क्षयाय भविष्यति।

Answer:

ମେଣ୍ଢା ଓ ରୋଷେୟାମାନଙ୍କର ଏହି କଳି ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ବିନାଶ ନିମନ୍ତେ କାରଣ ହେବ।

Question 5.

यद्वानरवसया अश्वानां वह्निदाहदोषः प्रशाम्यति।

Answer:

ଯେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ଚର୍ବି ବା ମଜ୍ଜାଦ୍ଵାରା ଅଶୁମାନଙ୍କର ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହ ଦୋଷ ଶାନ୍ତ ହେବ।

Question 6.

एवं निश्चित्य सर्वान् वानररानहूय रहसि प्रोवाच।

Answer:

ଏହିପରି ସ୍ଥିରକରି ସେ ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ଡାକି ଏକାନ୍ତରେ କହିଲା।

Question 7.

भवतो वृद्धभावाद् वुद्धिवैकल्यं संजातं येनैतद्ब्रवीषि।

Answer:

ଯେହେତୁ ଏହା କହୁଛ, ତୁମର ବାର୍ଦ୍ଧକ୍ୟ ହେତୁ ବୁଦ୍ଧି ବିଭ୍ରମ ହେଲାଣି।

Question 8.

एवमभिधाय सर्वांस्तान् परित्यज्य स यूथाधिपोऽटव्यां गतः।

Answer:

ଏହିପରି କହି ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ଛାଡ଼ି ସେ ବାନରଦଳପତି ବନକୁ ଚାଲିଗଲା।

Question 9.

अत्रान्तरे राजा सविषाद: शालिहात्रज्ञान् वैद्यानहूय प्रोवाच।

Answer:

ଏହାପରେ ରାଜା ବିଷାଦର ସହ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରନିଦାନ ଜାଣିଥିବା ବୈଦ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କୁ ଡାକି କହିଲେ।

Question 10.

तेऽपि शास्त्राणि विलोक्य प्रोचुः।

Answer:

ସେମାନେ ବି ଶାସ୍ତ୍ରଗୁଡ଼ିକୁ ଦେଖୁ କହିଲେ।

Question 11.

अथ तेन वृद्धवानरेण कुत्रचित् पिपासाकुलेन भ्रमता पद्मिनीखण्डमण्डितं सरः समासादितम्।

Answer:

ଏହାପରେ ତୃଷାରେ ବ୍ୟାକୁଳ ହୋଇ ସେଇ ବୃଦ୍ଧ ବାନରଟି ବୁଲୁ ବୁଲୁ ପଦ୍ମଲତାବିମଣ୍ଡିତ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀଟିଏ ପାଇଲା।

Question 12.

ततचिन्तितं नूनमत्र जलान्ते दृष्टग्राहेण भाव्यम्।

Answer:

ତାହାପରେ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା ନିଶ୍ଚିତ ଏହି ଜଳ ମଧ୍ଯରେ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ କୁମ୍ଭୀରଟିଏ ଥାଇପାରେ।

Question 13.

तत् पद्मिनीनालमादाय दूरस्थोऽपि जलं पिवामि।

Answer:

ତେଣୁ ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ଟିଏ ଆଣି ଦୂରରୁ ଥାଇ ଜଳ ପାନ କରିବି।

Question 14.

भो अत्र यः सलिले प्रवेशं करोति स मे भक्ष्य इति।

Answer:

ହେ ! ଯିଏ ଏହି ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରେ ସେ ମୋର ଖାଦ୍ୟ।

Question 15.

तन्नास्ति धूर्ततरस्त्वत्समोऽन्यो यत्पानीयमनेन विधिना पिवसि।

Answer:

ଯେହେତୁ ତୁମେ ଜଳ ଏହି ଉପାୟରେ ପିଉଛ ତେଣୁ ତୁମ ପରି ଅତିଚତୁର ଅନ୍ୟ କେହି ନାହିଁ।

Question 16.

वानर आह-अस्ति मे भूपतिना सहात्यन्तं वैरम्।

Answer:

ବାନର କହିଲା – ମୋର ରାଜାଙ୍କ ସହ ଘୋର ଶତ୍ରୁତା ଅଛି।

Question 17.

अस्ति कुत्रचिदरण्ये गुप्ततरं महत्सरो धनदनिर्मितम्।

Answer:

କୌଣସି ଏକ ବନରେ କୁବେରଙ୍କ ନିର୍ମିତ ଅତିଗୁପ୍ତ ବଡ଼ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀଟିଏ ଅଛି।

Question 18.

रत्नमालासनाथं सरोऽस्ति क्वापि?

Answer:

କେଉଁଠି ରତ୍ନମାଳାଥୁବା ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀଟିଏ ଅଛି କି?

Question 19.

तथानुष्ठिते भूपतिना सह रत्नमालालोभेन सर्वे कलत्रभृत्याः प्रस्थिताः।

Answer:

ସେହିପରି କରନ୍ତେ ରାଜାଙ୍କ ସହ ରତ୍ନମାଳା ଲୋଭରେ ସ୍ତ୍ରୀ ଓ ଚାକର ସମସ୍ତେ ପ୍ରସ୍ଥାନ କଲେ ।

Question 20.

देव! अर्धोदिते सूर्येऽत्र प्रविष्टानां सिद्धिर्भवति।

Answer:

ହେ ଦେବ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟ ଅର୍ଥ ଉଦିତ ହେଲେ ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟ ଲୋକର ସିଦ୍ଧି ହୋଇଥାଏ।

Question 21.

अथ प्रविष्टास्ते लोकाः सर्वे भक्षिता राक्षसेन।

Answer:

ଏହାପରେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିଥିବା ସମସ୍ତ ଲୋକଙ୍କୁ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କଲା।

Question 22.

तत्त्वया मम कुलक्षयः कृतो मया पुनस्तवेति।

Answer:

ତେଣୁ ତୁମେ ମୋର ବଂଶନାଶ କଲ, ମୁଁ ବି ତୁମର କୁଳ ବା ବଂଶ ନାଶ କଲି।

संक्षेपेण उत्तरं लिखत-

Question 1.

चन्द्रभूपतेः पुत्राः नित्यं किं कुर्वन्ति?

Answer:

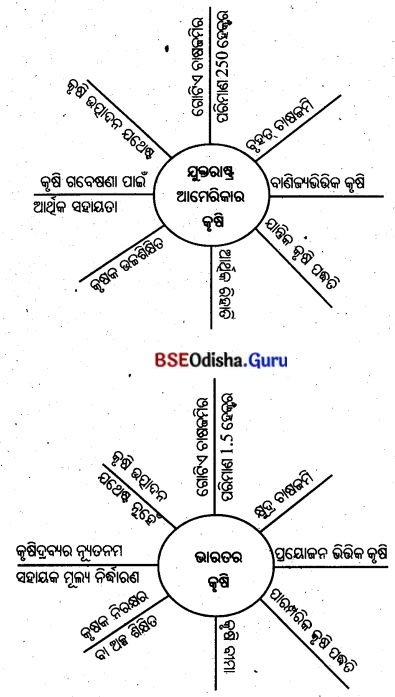

ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିଙ୍କର ପୁତ୍ରମାନେ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦରେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କ ସହିତ କ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରେ ରତ ରହୁଥିଲେ ଓ ସେମାନଙ୍କୁ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ଅନେକ ପ୍ରକାରର ଖାଦ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ଦେଇ ପୋଷଣ କରୁଥିଲେ। ସେହି ରାଜପୁରୀରେ ଛୋଟ ରାଜକୁମାରମାନଙ୍କର ବାହନଯୋଗ୍ୟ ଏକ ମେଷପଲ ମଧ୍ୟ ଥିଲା । ଏମାନଙ୍କ ସହ ପୁତ୍ରମାନେ କ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରତ ଥିଲେ ।

Question 2.

वानरयूथाधिपः वानरान् किमध्यापयति स्म?

Answer:

ବାନରଯୂଥାଧୂପତି ଶୁକ୍ର, ବୃହସ୍ପତି ଓ ଚାଣକ୍ୟଙ୍କର ନୀତିଶାସ୍ତ୍ରମାନ ଜାଣିଥିଲେ ଓ ତଦନୁସାରେ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟ କରୁଥିଲେ। ଏହିସବୁ ନୀତିଶାସ୍ତ୍ରମାନ ସେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଶିକ୍ଷା ଦେଉଥିଲେ।

Question 3.

मेष: महानसे किं करोति?

Answer:

ରାଜଉଆସରେ ଥିବା ମେଣ୍ଢାପଲ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ଏକ ମେଣ୍ଢା ନିଜର ଜିହ୍ବାଲାଳସା ହେତୁରୁ ଦିନରାତି ରନ୍ଧନଶାଳାରେ ପଶି ଯାହାକିଛି ଦେଖୁଥିଲା, ତାହା ଖାଇଯାଉଥିଲା।

Question 4.

मेषसूपकारयोः कलहविषये वानरयूथपस्य का चिन्ता जाता?

Answer:

ମେଣ୍ଢା ଓ ପାଚକମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ହେଉଥିବା କଳହ ବିଷୟରେ ବାନରଯୂଥର ଅଧୂପତି ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା ଯେ– ଅହୋ, ମେଷ ଓ ପାଚକଙ୍କର ଏହି କଳହ ଶେଷରେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ବିନାଶର କାରଣ ହେବ ଏଥିରେ ତିଳେମାତ୍ର ସନ୍ଦେହ ନାହିଁ । ମେଷ ଅନ୍ନଭୋଜନ ପାଇଁ ଲୋଲୁପ ଓ ପାଚକମାନେ ନିତାନ୍ତ କ୍ରୋଧୃତ ହୋଇ ତାଙ୍କୁ ଯାହା ପାଉଛନ୍ତି ସେଥିରେ ପିଟୁଛନ୍ତି । ଯଦି କେବେ ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଠରେ ପିଟିବେ ତେବେ ପ୍ରଚୁର ଲୋମ ଥିବା ମେଷଟି ଜଳିଉଠିବ ଓ ନିକଟସ୍ଥ ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବ ସେଠାରେ ପ୍ରଚୁର ତୃଣ ଥିବାରୁ ତାହା ଜଳିଉଠିବ । ଅଶ୍ଵମାନେ ମଧ୍ୟ ପୋଡ଼ିଯିବେ । ଅଶୁମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଦୋଷ ପ୍ରଶମିତ ପାଇଁ ଶେଷରେ ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନେ ହିଁ ମରାଯିବେ । ଏହିପରି ଚିନ୍ତା ବାନରଯୂଥପତିର ଜାତ ହୋଇଥିଲା ।

Question 5.

मदोद्धता वानराः यूधाधिपं किं प्रोचुः?

Answer:

ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ମେଷ ଓ ସୂପକାର କଳହରୁ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ବିନାଶ ଆଶଙ୍କା କରି ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦ ଛାଡ଼ି ଚାଲିଯିବାକୁ ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ କହିଲା । ତାହାର ଏପରି ଅପ୍ରିୟ ବଚନ ଶୁଣି ମଦୋଦ୍ଧତ ବାନରମାନେ ଉଚ୍ଚହାସ୍ୟ କରି କହିଲେ– ‘‘ଓ ! ବାର୍ଦ୍ଧକ୍ୟ ହେତୁରୁ ତୁମର ବୁଦ୍ଧି ବିଚଳିତ ହେଲାଣି । ସେଥିପାଇଁ ଏପରି କହୁଛ । ଏହି ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦରେ ସ୍ଵର୍ଗ ସମାନ ସୁଖଭୋଗ, ରାଜପୁତ୍ରମାନଙ୍କ ସ୍ୱହସ୍ତରେ ପ୍ରଦତ୍ତ ବିବିଧ ଅମୃତତୁଲ୍ୟ ଭୋଜ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ଆମେମାନେ ବନ ମଧ୍ୟରେ କଷାୟ, କଟୁ, ତିକ୍ତ, କ୍ଷାର, ରୁକ୍ଷ ଫଳ ଖାଇପାରିବୁ ନାହିଁ ।’’

Question 6.

अश्वाः कथं दग्धशरीरः संजाताः?

Answer:

ପାଚକମାନଙ୍କଦ୍ୱାରା ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଷ୍ଠଖଣ୍ଡର ପ୍ରହାର ଖାଇ ମେଷଟି ଜ୍ଵଳନ୍ତ ଶରୀରରେ ଚିତ୍କାର କରି କରି ନିକଟବର୍ତ୍ତୀ ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । ସେଠାରେ ସେ ତୃଣପୂର୍ବ ଭୂମିରେ ଲୋଟିବାରୁ ସର୍ବତ୍ର ଏପରି ଅଗ୍ନିଶିଖା ଉଠିଲା ଯେ କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ଵ ଚକ୍ଷୁ ହରାଇ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ପଡ଼ିଲେ । କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ବ ବନ୍ଧନ ଛିନ୍ନକରି ଅର୍ଦ୍ଧଦଗ୍ଧ ଶରୀରରେ ହେସ୍ରାରାବ କରି ଇତସ୍ତତଃ ଧାଇଁବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲେ । ଏହିପରିଭାବେ ଅଶ୍ଵମାନେ ଦଗ୍ଧଶରୀରଯୁକ୍ତ ହୋଇଥିଲେ।

Question 7.

शालिहात्रेण अश्वदाहोपशमनविषये किमुक्तम्?

Answer:

ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରଶାସ୍ତ୍ରଜ୍ଞ ବୈଦମାନେ ଅଶ୍ୱମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ବ୍ୟଥାର ଉପଶମ ଉପାୟ ବିଷୟ ଶାସ୍ତ୍ର ଦେଖୁ କହିଲେ– ମହାରାଜ ! ଏ ବିଷୟରେ ଭଗବାନ୍ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର କହିଛନ୍ତି ଯେ– ‘‘ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ହେଲେ ଅନ୍ଧକାର ଯେପରି ଦୂର ହୋଇଯାଏ । ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ମେଦଦ୍ଵାରା ଅଶ୍ଵମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ରୋଗ ସେହିପରି ବିନଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇଯାଏ । ତେଣୁ ଅତି ଶୀଘ୍ର ଏହି ଚିକିତ୍ସା କରାଯାଉ, ଯେପରିକି ଅଶୁମାନେ ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହ ଯୋଗୁଁ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ନ ପଡ଼ନ୍ତି।’’

Question 8.

वानरयूथपः कथं चन्द्रभूपतेः अपकृत्यं कर्त्तुम् ऐच्छत्?

Answer:

ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ପୁତ୍ର, ପୌତ୍ର, ଭ୍ରାତୃକ୍ଷୁତ୍ର, ଭାଗିନେୟ ପ୍ରଭୃତିଙ୍କର ମରଣ ଦେଖୁ ଗଭୀର ବିଷାଦରେ ମଗ୍ନ ହୋଇ ଅନାହାରରେ ରହି ବନରୁ ବନାନ୍ତର ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲା । ଏହାପରେ ସେ ଏ ଅଧମ ରାଜାର ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେଇ କିପରି ତା’ର ଏବଂ ତା’ବଂଶର ଅନିଷ୍ଟ ସାଧନ କରିବ ସେ ବିଷୟରେ ଚିନ୍ତା କରିବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲା ।

Question 9.

राक्षसः किमर्थं वानरं धूर्त्ततर इत्युक्तवान्?

Answer:

ବୃଦ୍ଧ ବାନର ବନ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ପିପାସାକୁଳ ହୋଇ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରୁ କରୁ କମଳ ପରିପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଏକ ସରୋବର ଦେଖୁଲା । ସେଠାରେ ସେ ବନବାସୀଜନଙ୍କର ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବାର ପଦଚିହ୍ନ ଦେଖୁଲା ହେଲେ ଫେରିବାର ପଦଚିହ୍ନ ଦେଖୁଲା ନାହିଁ । ଏଥୁରୁ ସେ ଅନୁମାନ କଲା ଯେ କେହି ଦୁଷ୍ଟପ୍ରାଣୀ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ରହିଛି । ତେଣୁ ଏକ ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ଆଣି ଦୂରରେ ରହି ସେହି ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ଜଳପାନ କଲା । ବାନରର ଏତାଦୃଶ କଳକୌଶଳକୁ ଦେଖୁ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଥିବା ରାକ୍ଷସ ତାକୁ ଅତ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଧୂର୍ଜ୍ଜତର ବା ଚତୁର ବୋଲି କହିଥିଲା।

Question 10.

रत्नमालाविषये वानरः नरपतिं किम् अवदत्?

Answer:

ରତ୍ନମାଳା ବିଷୟରେ ବାନର ରାଜାକୁ କହିଲା– ଗୋଟିଏ ଅରଣ୍ୟ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଏକ ଅତି ଗୁପ୍ତ ସରୋବର ଅଛି । ତାହାକୁ ସ୍ବୟଂ କୁବେର ନିର୍ମାଣ କରିଅଛନ୍ତି । ରବିବାର ଦିନ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ସମୟରେ ଯଦି କେହି ଉକ୍ତ ସରୋବରରେ ବୁଡ଼ ପକାଏ ତେବେ ସେ କୁବେରଙ୍କ ପ୍ରସାଦରୁ ଏହିପରି ରତ୍ନମାଳାରେ କଣ୍ଠକୁ ସୁଶୋଭିତ କରି ଜଳରୁ ବାହାରି ଆସିବ ।

Question 11.

सरसि प्रविष्टाः जनाः कुत्र गता:?

Answer:

ଲୋକମାନେ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତେ ସରୋବର ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଥିବା ରାକ୍ଷସ ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କୁ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କଲା । ସେମାନେ ଅନେକବେଳ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଜଳରୁ ନ ବାହାରିବାରୁ ରାଜା ବିଳମ୍ବର କାରଣ ପଚାରନ୍ତେ ବାନର କହିଲା– ଆରେ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ରାଜା ! ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଥିବା ରାକ୍ଷସ ତୋର ପରିଜନକୁ ଖାଇସାରିଛି ।

Question 12.

वानरेण भूपतिः कथं न विनाशित:?

Answer:

ବାନର ନିଜର କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଜନିତ ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେବାପାଇଁ ରାଜାଙ୍କର ସମସ୍ତ ପରିଜନକୁ ରାକ୍ଷସଦ୍ବାରା ମରାଇଥିଲା । ହେଲେ ସ୍ବୟଂ ରାଜା ବାନରର ପ୍ରଭୁ ହୋଇଥିବାରୁ ତାଙ୍କୁ ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରାଇଲା ନାହିଁ, ଅର୍ଥାତ୍ ମାରିଲା ନାହିଁ ।

दीर्घप्रश्नोत्तराणि

Question 1.

चन्द्र भूपतिकथासारं निजभाषया वर्णयत।

Answer:

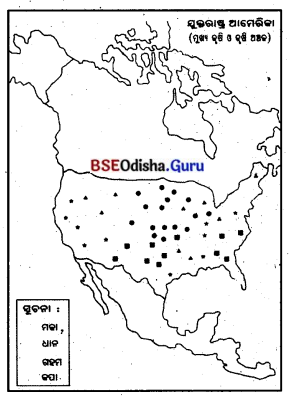

ଗୋଟିଏ ନଗରରେ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ର ନାମକ ଜଣେ ରାଜା ବାସ କରୁଥିଲେ । ତାଙ୍କର ପୁତ୍ରମାନେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କ ସହିତ କ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରେ ରତ ରହୁଥିଲେ ଓ ସେମାନଙ୍କୁ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ଅନେକପ୍ରକାର ଖାଦ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ଦେଇ ପୁଷ୍ଟ କରୁଥିଲେ । ଏହି ବାନରଯୂଥର ଅଧୂତି ଶୁକ୍ର, ବୃହସ୍ପତି ଓ ଚାଣକ୍ୟଙ୍କର ନୀତିଶାସ୍ତ୍ରମାନ ଜାଣିଥୁଲା ଓ ତଦନୁସାରେ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟ କରୁଥିଲା । ସେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଶିକ୍ଷା ଦେଉଥିଲା । ସେହି ରାଜପୁରୀରେ ଛୋଟ ରାଜକୁମାରମାନଙ୍କର ବାହନଯୋଗ୍ୟ ଗୋଟିଏ ମେଷପଲ ଥିଲା । ସେହି ମେଷପଲ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ଗୋଟିଏ ମେଷ ଜିହ୍ବାଲାଳସା ହେତୁରୁ ଦିବାରାତ୍ର ରନ୍ଧନଶାଳାରେ ପଶି ଯାହାକିଛି ଦେଖୁଥିଲା, ତାହା ଖାଇଯାଉଥିଲା । ପାଚକମାନେ କାଷ୍ଠ, ମୃତ୍ତିକାନିର୍ମିତ ପାତ୍ର, କାଂସ୍ୟପାତ୍ର ବା ତାମ୍ରପାତ୍ର ଯାହାକିଛି ପାଉଥିଲେ ସେଥିରେ ତାକୁ ପିଟୁଥିଲେ ।

ବାନରଯୂଥର ଅଧୂପତି ଏହା ଦେଖ୍ ଚିନ୍ତା କରିବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲା – ଅହୋ, ମେଷ ଓ ପାଚକଙ୍କର ଏହି କଳହ ଶେଷରେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ବିନାଶର କାରଣ ହେବ । ଏ ମେଷଟି ଅନ୍ନଭୋଜନ ପାଇଁ ଲୋଲୁପ ଓ ପାଚକମାନେ ନିତାନ୍ତ କ୍ରୁଦ୍ଧ ହୋଇ ଯାହାକିଛି ନିକଟରେ ଦେଖୁଛନ୍ତି ସେଥିରେ ତାକୁ ପିଟୁଛନ୍ତି । ଯଦି କେବେ ପାଖରେ ଅନ୍ୟ କିଛି ନପାଇ ପାଚକମାନେ ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଷ୍ଠଖଣ୍ଡରେ ତାକୁ ପ୍ରହାର କରନ୍ତି ତେବେ ମେଷର ଦେହରେ ଥିବା ପ୍ରଚୁର ଲୋମରେ ସାମାନ୍ୟ ଅଗ୍ନି ଲାଗିଲେ ମଧ୍ୟ ପ୍ରଜ୍ବଳିତ ହୋଇଉଠିବ । ତା’ପରେ ସେ ନିକଟବର୍ତ୍ତୀ ଅଶ୍ମଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବ । ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରଚୁର ତୃଣ ଥିବାରୁ ତାହା ଜଳି ଉଠିବ । ଫଳରେ ଅଶ୍ଵମାନେ ଅଗ୍ନିରେ ପୋଡ଼ିଯିବେ । ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର ଅଶ୍ୱଶାସ୍ତ୍ରରେ କହିଅଛନ୍ତି – ବାନରର ଚର୍ବିଦ୍ଵାରା ଅଶୁମାନଙ୍କର ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହ ପ୍ରଶମିତ ହୁଏ । ଏହିପରି ଦିନେ ଅବଶ୍ୟ ଘଟିବ । ଏକଥା ନିଶ୍ଚିତ ।

ଏହିପରି ବିଚାର କରି ସେ ବାନର ଯୂଥପତି ସବୁ ବାନରଙ୍କୁ ଡାକି ଏକାନ୍ତରେ କହିଲା –

ପାଚକମାନଙ୍କର ମେଷ ସହିତ ଯେଉଁ କଳହ ଚାଲିଛି, ତାହା ପରିଣାମରେ ଆମ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ଯେ କ୍ଷୟସାଧନ କରିବ ଏଥୁରେ ସନ୍ଦେହ ନାହିଁ । ୧ ।

ଯେଉଁ ଗୃହରେ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ଅକାରଣରେ କଳହ ଲାଗିଥାଏ, ପ୍ରାଣ ରଖୁବାକୁ ଇଚ୍ଛା ଥିଲେ, ସେ ଗୃହକୁ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ଚାଲିଯିବା ଉଚିତ । ୨ ।

ଆହୁରି ମଧ୍ୟ କଳହ ହେତୁ ଗୃହର, କୁବାକ୍ୟ ହେତୁ ବନ୍ଧୁତ୍ଵର, ଦୁଷ୍ଟରାଜାଙ୍କ ହେତୁରୁ ରାଜ୍ୟର ଓ କୁକର୍ମ ହେତୁରୁ ମନୁଷ୍ୟର ଯଶର ବିନାଶ ଘଟିଥାଏ । ୩ ।

ଅତଏବ ଆମ ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କର ବିନାଶ ହେବା ପୂର୍ବରୁ ଏ ରାଜନଅରକୁ ଛାଡ଼ି ବନକୁ ପଳାଇଯିବା । ତାହାର ଏହି ଅପ୍ରିୟ ବଚନ ଶୁଣି ମନ୍ଦୋଦ୍ଧତ ବାନରମାନେ ଉଚ୍ଚ ହାସ୍ୟ କରି କହିଲେ, ‘ଓ ! ବାର୍ଦ୍ଧକ୍ୟ ହେତୁରୁ ତୁମର ବୁଦ୍ଧି ବିଚଳିତ ହେଲାଣି । ସେଥିପାଇଁ ଏପରି କହୁଛ । କୁହାଯାଇଅଛି –

ବାଳକ ଓ ବୃଦ୍ଧ ଉଭୟଙ୍କର ମୁଖ ଦନ୍ତହୀନ; ଉଭୟଙ୍କ ମୁଖରୁ ସର୍ବଦା ଲାଳ ଝରୁଥାଏ । କୌଣସି ବିଷୟରେ ଏ ଦୁହିଁଙ୍କର ବିଶେଷତଃ ବୃଦ୍ଧର ବୁଦ୍ଧି ସ୍ତୁରେ ନାହିଁ । ୪ ।

ଏଠାରେ ସ୍ଵର୍ଗ ସମାନ ସୁଖଭୋଗ, ରାଜପୁତ୍ରମାନଙ୍କ ସ୍ୱହସ୍ତପ୍ରଦତ୍ତ ବିବିଧ ଅମୃତତୁଲ୍ୟ ଭୋଜ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ଆମେମାନେ ବନ ମଧ୍ୟରେ କଷାୟ, କଟୁ, ତିକ୍ତ, କ୍ଷାର, ରୁକ୍ଷ ଫଳ ଖାଇପାରିବୁ ନାହିଁ ।’’ ଏହା ଶୁଣି ବାନରପତି ଅଶ୍ରୁପ୍ଲାବିତ ନେତ୍ରରେ କହିଲା – ଆରେ ରେ ମୂର୍ଖ ! ତୁମେମାନେ ଏ ସୁଖର ପରିଣାମ ଜାଣିପାରି ନାହିଁ । ପାପକର୍ମର ରସାସ୍ଵାଦନ ସଦୃଶ ଏ ସୁଖର ପରିଣାମ ବିଷମୟ ହେବ । କୁଳର ବିନାଶ ମୁଁ ନିଜେ ଦେଖୁପାରିବି ନାହିଁ । ମୁଁ ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନ ବନକୁ ଚାଲିଯାଉଛି । କୁହାଯାଇଛି – ମିତ୍ର ବିପଦଗ୍ରସ୍ତ ହେବା, ନିଜର ସ୍ଥାନ ଅନ୍ୟଦ୍ଵାରା ଉପୀଡ଼ିତ ହେବା, ଦେଶଭଙ୍ଗ, କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ – ଏସବୁ ଯେଉଁମାନେ ଦେଖନ୍ତି ନାହିଁ, ସେମାନେ ଧନ୍ୟ । ୫ ।

ପୃଥପତି ଏହା କହି, ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରଙ୍କୁ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ବନକୁ ଚାଲିଗଲା ।

ସେ ଯିବାପରେ ଦିନେ ସେହି ମେଷଟି ରନ୍ଧନଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । ପାଚକ ଅନ୍ୟ କିଛି ନପାଇ ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଷ୍ଠଖଣ୍ଡରେ ତାକୁ ପ୍ରହାର କରିବାରୁ ସେ ଜ୍ଵଳନ୍ତ ଶରୀରରେ ଚିତ୍କାର କରି କରି ନିକଟବର୍ତୀ ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । ସେଠାରେ ସେ ତୃଣପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଭୂମିରେ ଲୋଟିବାରୁ ସର୍ବତ୍ର ଏପରି ବହ୍ନିଶିଖା ଉଠିଲା ଯେ କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ଵ ଚକ୍ଷୁ ହରାଇ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ପଡ଼ିଲେ । କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ୱ ବନ୍ଧନ ଛିନ୍ନକରି ଅର୍ଦ୍ଧଦଗ୍ଧ ଶରୀରରେ ବ୍ରେଷାରାବ କରି ଇତସ୍ତତଃ ଧାଇଁବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲେ । ଏହା ଫଳରେ ଲୋକମାନେ ବ୍ୟାକୁଳ ହୋଇପଡ଼ିଲେ ।

ଏହି ଅବସ୍ଥାରେ ରାଜା ବିଷଣ୍ଣ ହୋଇ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର ଶାସ୍ତ୍ରଜ୍ଞ ବୈଦ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କୁ ଡକାଇ କହିଲେ, ‘‘ଏହି ଅଶ୍ୱମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ବ୍ୟଥାର ଉପଶମ ପାଇଁ କୌଣସି ଉପାୟ କୁହନ୍ତୁ ।’’ ସେମାନେ ଶାସ୍ତ୍ର ଦେଖୁ କହିଲେ, ମହାରାଜ ! ଏ ବିଷୟରେ ଭଗବାନ୍ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର କହିଅଛନ୍ତି –

ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ହେଲେ ଅନ୍ଧକାର ଯେପରି ଦୂର ହୋଇଯାଏ, ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ମେଦଦ୍ବାରା ଅଶ୍ଵମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ରୋଗ ସେହିପରି ବିନଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇଯାଏ । ୬ ।

ତେଣୁ ଅତିଶୀଘ୍ର ଏହି ଚିକିତ୍ସା କରାଯାଉ, ଯେପରିକି ଅଶୁମାନେ ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହ ଯୋଗୁଁ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ନ ପଡ଼ନ୍ତି । ରାଜା ଏହା ଶୁଣି ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରଙ୍କୁ ବଧ କରିବାପାଇଁ ଆଦେଶ ଦେଲେ । ଅଧୂକ କହିବା ନିଷ୍ପ୍ରୟୋଜନ, ଯଷ୍ଟି, ପ୍ରସ୍ତର ପ୍ରଭୃତି ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ସମସ୍ତ ବାନର ନିହତ ହେଲେ ।

ବାନର ଯୂଥପତି ପୁତ୍ର, ପୌତ୍ର, ଭ୍ରାତୁମ୍ପୁତ୍ର, ଭାଗିନେୟ ପ୍ରଭୃତିଙ୍କର ମରଣ ଦେଖୁ ଗଭୀର ବିଷାଦରେ ମଗ୍ନହୋଇ ଅନାହାରରେ ରହି ବନରୁ ବନ୍ୟନ୍ତର ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲା । ସେ ମନେ ମନେ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା, ମୁଁ ଏ ଅଧମ ରାଜାର ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେଇ କିପରି ତା’ର ଅନିଷ୍ଟସାଧନ କରିବି । କୁହାଯାଇଛି –

ଏ ସଂସାରରେ ଯେଉଁ ଲୋକ ଭୟ ହେତୁରୁ ଅଥବା ଲୋଭ ହେତୁରୁ ନିଜ ନିଜ କୁଳ ପ୍ରତି ଶତ୍ରୁର ଅତ୍ୟାଚାରକୁ ସହିଯାଏ, ସେ ପୁରୁଷମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ନିତାନ୍ତ ଅଧମ ଅଟେ । ୭ ।

ଏହାପରେ ସେହି ବୃଦ୍ଧ ବାନର ପିପାସାକୁଳ ହୋଇ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରୁ କରୁ କମଳ ପରିପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଗୋଟିଏ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ନିକଟରେ ପହଞ୍ଚିଲା । ସେ ସୂକ୍ଷ୍ମଭାବରେ ନିରୀକ୍ଷଣ କରି ଦେଖିଲା ଯେ ବନବାସୀ ମନୁଷ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କର ସରୋବରରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବାର ପଦଚିହ୍ନମାନ ଅଛି, କିନ୍ତୁ ଫେରି ଆସିବାର ପଦଚିହ୍ନ ନାହିଁ । ତହୁଁ ସେ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା – ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ନିଶ୍ଚୟ ଗୋଟିଏ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ କୁମ୍ଭୀର ଅଛି । ତେଣୁ ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ଆଣି ଦୂରରେ ରହି ସେହି ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ଜଳପାନ କରିବି । ସେହିପରି ଜଳପାନ କରନ୍ତେ ଗଳାରେ ରନୁମାଳା ପରିଧାନ କରିଥିବା ଗୋଟିଏ ରାକ୍ଷସ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ମଧ୍ଯରୁ ବାହାରି ଆସି କହିଲା, ଯେ କେହି ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀର ଜଳମଧ୍ୟରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରେ, ମୁଁ ତାକୁ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କରେ । କିନ୍ତୁ ଏପରି କୌଣସି ଚତୁର ଲୋକ ନାହିଁ, ଯେ କି ତୁମ ଭଳି ଏ ଉପାୟରେ ଜଳପାନ କରିବ ।

ତେଣୁ ମୁଁ ତୁମ ଉପରେ ସନ୍ତୁଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇଅଛି । ମନର ଅଭିଳାଷ ଅନୁସାରେ ବର ପ୍ରାର୍ଥନା କର । ବାନର କହିଲା, ତୁମର ଭୋଜନ କରିବାର ଶକ୍ତି କେତେ ? ରାକ୍ଷସ ଉତ୍ତର ଦେଲା, ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲେ ଶତ, ସହସ୍ର, ଅୟୁତ, ଲକ୍ଷ ପ୍ରାଣୀଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଭୋଜନ କରିପାରିବି । ମାତ୍ର ବାହାରେ ଥିଲାବେଳେ ମୋତେ ସାମାନ୍ୟ ଶୃଗାଳ ମଧ୍ୟ ଅପମାନିତ କରିପାରେ । ବାନର କହିଲା, ଜଣେ ରାଜା ସହିତ ମୋର ଘୋର ଶତ୍ରୁତା ଅଛି । ଯଦି ତୁମେ ମୋତେ ତୁମର ଏହି ରହାରଟି ଦେବ, ତାହାହେଲେ ମୁଁ ମୋର କଥା ଚାତୁରୀରେ ଲୋଭ ଦେଖାଇ ସେ ରାଜାକୁ ତା’ର ପରିବାର ସହିତ ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରାଇବି । ରାକ୍ଷସ ତାହାର ଏହି ଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟ ବାକ୍ୟ ଶୁଣି ରହାରଟି ଦେଇ କହିଲା, ହେ ମିତ୍ର ! ଯାହା ଉଚିତ ମନେକରୁଛ, ତାହା କର ।

ବାନର ମଧ୍ଯ ରହାରରେ ନିଜର କଣ୍ଠଦେଶକୁ ସୁଶୋଭିତ କରି ବୃକ୍ଷ ଓ ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦମାନଙ୍କ ଉପରେ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିବାରୁ ଲୋକେ ତାହାକୁ ଦେଖୁ ପଚାରିଲେ, ହେ ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ! ତୁମେ ଏତେ କାଳ ହେଲା କେଉଁଠାରେ ଥିଲ ? ଏଡ଼େ ସୁନ୍ଦର ରମାଳା କାହୁଁ ପାଇଲ ? ଏହାର ତେଜ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟକିରଣକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ତିରସ୍କାର କରୁଛି । ବାନର କହିଲା, ଗୋଟିଏ ଅରଣ୍ୟ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଏକ ଅତି ଗୁପ୍ତ ସରୋବର ଅଛି । ତାହାକୁ ସ୍ଵୟଂ କୁବେର ନିର୍ମାଣ କରିଅଛନ୍ତି । ରବିବାର ଦିନ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ସମୟରେ ଯଦି କେହି ଉକ୍ତ ସରୋବରରେ ବୁଡ଼ପକାଏ ତେବେ ସେ କୁବେରଙ୍କ ପ୍ରସାଦରୁ ଏହିପରି ରନ୍ମାଳାରେ କଣ୍ଠକୁ ସୁଶୋଭିତ କରି ଜଳରୁ ବାହାରିଆସେ ।

ଏହାପରେ ରାଜା ଏହା ଶୁଣିପାରି ସେହି ବାନରକୁ ଡାକି ପଚାରିଲେ, ହେ ପୃଥାଧୂପ ! ଏ କଥା କ’ଣ ସତ୍ୟ ? ରନ୍ମାଳାରେ ପରିପୂର୍ଣ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ କେଉଁଠାରେ ଅଛି ? ବାନର କହିଲା, ହେ ପ୍ରଭୁ ! ପ୍ରତ୍ୟକ୍ଷରେ ମୋ ଗଳାରେ ପଡ଼ିଥିବା ଏହି ରନ୍ମାଳା ଦେଖୁ ଆପଣଙ୍କର ବିଶ୍ଵାସ ହେବ । ତେଣୁ ଯଦି ଆପଣଙ୍କର ରନ୍ଧମାଳାର ପ୍ରୟୋଜନ ଥାଏ, ତାହାହେଲେ କାହାରିକୁ ମୋ ସଙ୍ଗେ ପଠାନ୍ତୁ ଯେ ଦେଖାଇଦେବି । ଏହା ଶୁଣି ରାଜା କହିଲେ, ସେପରି ହେଲେ ମୁଁ ନିଜେ ମୋର ସମସ୍ତ ପରିବାର ସହିତ ଯିବି । ତେବେ ଅନେକ ରନ୍ମାଳା ପାଇପାରିବୁ । ବାନର କହିଲା, ତାହାହିଁ କରନ୍ତୁ । ସେହିପରି କରାଯିବାରୁ ରନ୍ଥମାଳା ପାଇବା ଲୋଭରେ ରାଜାଙ୍କ ସହିତ ସବୁ ପନ୍ଥୀ ଓ ଭୃତ୍ୟ ପ୍ରଭୃତି ଚାଲିଲେ । ରାଜା ଦୋଳାରେ ବସି ଗଲେ । ବାନରକୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ରାଜାଙ୍କ କ୍ରୋଡ଼ରେ ବସାଇ ଅତି ସୁଖରେ ପ୍ରୀତିପୂର୍ବକ ନିଆଗଲା । ତେଣୁ ଯଥାର୍ଥରେ କୁହାଯାଇଛି –

‘‘ହେ ତୃଷ୍ଣାଦେବି ! ତୁମକୁ ନମସ୍କାର । ତୁମେ ଧନବନ୍ତ ଲୋକକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ଅକରଣୀୟ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟରେ ନିୟୋଜିତ କରୁଛ; ଦୁର୍ଗମ ସ୍ଥାନରେ ମଧ୍ୟ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରାଉଅଛି’’ | ୮ |

ପୁଣି ମଧ୍ଯ – ଯେ ଶତମୁଦ୍ରାର ଅଧିକାରୀ, ସେ ସହସ୍ର ପାଇବାକୁ ଲାଳାୟିତ । ଯାହାର ସହସ୍ରମୁଦ୍ରା ଅଛି ସେ ଲକ୍ଷମୁଦ୍ରା କାମନା କରୁଅଛି । ଯେ ଲକ୍ଷାଧୂପତି ସେ ରାଜ୍ୟ ଅଭିଳାଷ କରୁଅଛି ଓ ଯେ ରାଜପଦରେ ପ୍ରତିଷ୍ଠିତ ହୋଇଅଛି ସେ ସ୍ୱର୍ଗକାମନା କରୁଅଛି । ୯ ।

ଜରାକ୍ରାନ୍ତ ବ୍ୟକ୍ତିର କେଶ ଶୁକ୍ଳ ହୋଇଯାଏ, ଦନ୍ତଗୁଡ଼ିକ ଝଡ଼ିପଡ଼ନ୍ତି, ଚକ୍ଷୁ ଦୃଷ୍ଟିଶକ୍ତି ହରାଏ, କର୍ମ ଶୁଣିପାରେ ନାହିଁ । କିନ୍ତୁ କେବଳ ତୃଷ୍ଣା ହିଁ ତରୁଣ ହେଉଥାଏ । ୧୦ ।

ଏହାପରେ ସେହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ନିକଟରେ ଉପସ୍ଥିତ ହୁଅନ୍ତେ ବାନର ପ୍ରଭାତ କାଳରେ ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ କହିଲା, ଏଠାରେ ଅଧେ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ହେଲାବେଳକୁ ଯେଉଁମାନେ ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତି, ସେମାନେ ସିଦ୍ଧିଲାଭ କରନ୍ତି । ତେଣୁ ସମସ୍ତେ ଏକ ସଙ୍ଗରେ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତୁ । ଆପଣ ପରେ ମୋ ସହିତ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବେ । ତାହାହେଲେ ମୁଁ ଆପଣଙ୍କୁ ପୂର୍ବଦୃଷ୍ଟ ସ୍ଥାନକୁ ନେଇ ପ୍ରଚୁର ରନ୍ଧମାଳା ଦେଖାଇଦେବି ।

ଏହାପରେ ଲୋକମାନେ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ସେ ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କୁ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କଲା । ସେମାନେ ଅନେକବେଳ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଜଳରୁ ନ ବାହାରିବାରୁ ରାଜା ବାନରକୁ କହିଲେ, ହେ ପୃଥପତି ! ମୋର ଲୋକମାନେ ଏତେ ବିଳମ୍ବ କରୁଛନ୍ତି କାହିଁକି? ଏହା ଶୁଣିଲାମାତ୍ରେ ବାନର ତତ୍କ୍ଷଣାତ୍ ଏକ ବୃକ୍ଷକୁ ଆରୋହଣ କରି ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ କହିଲା, ଆରେ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ରାଜା ! ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଥିବା ରାକ୍ଷସ ତୋର ପରିଜନମାନଙ୍କୁ ଖାଇସାରିଛି । ମୁଁ କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଜନିତ ବୈରସାଧନ କରିଛି । ଏବେ ଯାଆ । ତୁ ମୋର ପ୍ରଭୁ ଥୁଲୁ ବୋଲି ତୋତେ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରାଇଲି ନାହିଁ । କଥ୍ତ ଅଛି –

କେହି ଉପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ଯୁପକାର ଓ ଅପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ୟପକାର କରିବ; କେହି ହିଂସା କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତିହିଂସା କରିବ; ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ସହିତ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଆଚରଣ କରିବ । ଏଥିରେ ମୁଁ କୌଣସି ଦୋଷ ଦେଖ୍ପାରୁନାହିଁ । ୧୧।

ତୁ ମୋର କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ କରିଥୁଲୁ; ମୁଁ ସେହିପରି ତୋର କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ କଲି । ଏହା ଶୁଣି ରାଜା କୋପାବିଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇ ପାଦରେ ଚାଲି ଚାଲି ଯେଉଁ ମାର୍ଗରେ ଆସିଥିଲେ ସେହି ମାର୍ଗରେ ଫେରିଗଲେ । ରାଜା ଚାଲିଯିବା ପରେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ତୃପ୍ତ ହୋଇ ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ବାହାରି ଆନନ୍ଦରେ କହିଲା–

ହେ ବାନର ତୁମେ ଧନ୍ୟ ! ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ଜଳ ପିଇ ତୁମ ଶତ୍ରୁକୁ ବିନାଶ କରିଅଛ; ମୋତେ ମିତ୍ର କରିପାରିଛ ଓ ରନ୍ଥମାଳାକୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ହରାଇ ନାହଁ । ୧୨ ।

Question 2.

चन्द्रभूपतिकथातः का शिक्षा लभ्यते?

Answer:

‘ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିକଥା’ରୁ ମୁଖ୍ୟତଃ ଯେଉଁ ନୀତିଶିକ୍ଷା ମିଳେ ତାହା ହେଇଛି –

‘‘ଯୋ ଲୌଲ୍ୟାତ୍ କୁରୁତେ କର୍ମ ନୈବୋଦର୍କମବେକ୍ଷତେ ।

ବିଡ଼ମ୍ବନାମବାପ୍ଲୋତି ସ ଯଥା ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିଃ ।।’’

ଅର୍ଥାତ୍, ଯେଉଁ ଲୋକ ଲୋଭପରବଶ ହୋଇ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟ କରେ ଓ ତା’ର ପରିଣାମ ବିଷୟରେ ଚିନ୍ତାକରେ ନାହିଁ, ସେ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତି ପରି ବିଡ଼ମ୍ବନା ପ୍ରାପ୍ତ ହୁଏ । ରତ୍ନମାଳା ଲୋଭରେ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତି ନିଜର ପରିବାର ସୃଜନମାନଙ୍କୁ ହରାଇଥିଲା । ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ସ୍ବବଂଶକ୍ଷକ୍ଷର ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେଇଥିଲା । ପୁନଶ୍ଚ ଏହି ବିଷୟରୁ ଯେଉଁ ଅନ୍ୟାନ୍ୟ ଶିକ୍ଷାମାନ ମିଳେ ତାହା ହେଉଛି –

- ଦୁଇଜଣଙ୍କର କଳହ ତୃତୀୟ ବ୍ୟକ୍ତିର ହାନି ବା କ୍ଷତି ଘଟାଇଥାଏ । ଯେପରିକି ପାଚକ ଓ ମେଷମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ କଳହର ପରିଣାମସ୍ଵରୂପ ଶେଷରେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର କ୍ଷୟସାଧନ ହୋଇଥିଲା।

- ଅକାରଣରେ ଯେଉଁ ଗୃହରେ କଳହ ହୁଏ, ପ୍ରାଣ ରକ୍ଷଣ ନିମନ୍ତେ ସେ ଗୃହକୁ ତ୍ୟାଗ କରିବା ଉଚିତ ।

- ବାର୍ଦ୍ଧକ୍ୟ ହେତୁରୁ ବୃଦ୍ଧର ବୁଦ୍ଧିସ୍ଫୁରଣ ହୁଏ ନାହିଁ ବୋଲି ଯେଉଁ ଧାରଣା ରହିଛି ତାହା ଅମୂଳକ ।

- ପାପକର୍ମର ରସାସ୍ଵାଦନ ସଦୃଶ ସୁଖର ପରିଣାମ ବିଷମୟ ହୁଏ ।

- ମିତ୍ରର ବିପଦ, ସ୍ବସ୍ଥାନ ଅନ୍ୟଦ୍ୱାରା ଉପୀଡ଼ିତ ହେବା, ଦେଶଭଙ୍ଗ କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ– ଏସବୁ ନ ଦେଖୁଥିବା ବ୍ୟକ୍ତି ଧନ୍ୟ ଅଟେ।

- ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ମେଦଦ୍ୱାରା ଅଶ୍ଵମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ଦୋଷ ଦୂରହେବା କଥା ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରଙ୍କଦ୍ୱାରା କୁହାଯାଇଛି ।

- ଏ ସଂସାରରେ ଯେଉଁ ଲୋକ ଭୟ ହେତୁରୁ ଅଥବା ଲୋଭ ହେତୁରୁ ନିଜ ନିଜ କୁଳ ପ୍ରତି ଶତ୍ରୁର ଅତ୍ୟାଚାରକୁ ସହିଯାଏ, ସେ ପୁରୁଷମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ନିତାନ୍ତ ଅଧମ ଅଟେ ।

- ତୃଷ୍ଣା ବା ଲୋଭ ଧନବନ୍ତକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ଅକରଣୀୟ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟରେ ନିୟୋଜିତ କରେ ଓ ଦୁର୍ଗମ ସ୍ଥାନରେ ମଧ୍ୟ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରାଇଥାଏ । ତୃଷ୍ଣା ମନ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଅଧିକ ପାଇବାର ଆଶା ବଢ଼ାଏ । ସବୁକିଛି ବୃଦ୍ଧତ୍ଵକୁ ପ୍ରାପ୍ତ ହୁଏ ହେଲେ ତୃଷ୍ଣା ହିଁ ତରୁଣ ହେଉଥାଏ ।

- କେହି ଉପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ଯୁପକାର ଓ ଅପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ୟପକାର କରିବ, କେହି ହିଂସା କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତିହିଂସା କରିବ; ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ସହିତ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଆଚରଣ କରିବ । ଏଥିରେ କିଛି ଦୋଷ ନଥାଏ ।

ଏହିଭଳି ବିବିଧ ପ୍ରକାର ଶିକ୍ଷଣୀୟ ପ୍ରସଙ୍ଗମାନ ଉକ୍ତ ବିଷୟରେ ଉଲ୍ଲେଖ ହୋଇଛି।

Question 3.

वानरयूथपतेः वैशिष्ट्यं प्रतिपाद्यताम्।

Answer:

ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ଶୁକ୍ର, ବୃହସ୍ପତି ଓ ଚାଣକ୍ୟଙ୍କର ନୀତିଶାସ୍ତ୍ରମାନ ଜାଣିଥିଲା ଓ ତଦନୁସାରେ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟ ମଧ୍ୟ କରୁଥିଲା । ସେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଶିକ୍ଷା ଦେଉଥିଲା । ମେଷ ଓ ସୂପକାରଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ହେଉଥିବା କଳହକୁ ଦେଖୁ ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ଏହା ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର କ୍ଷୟସାଧନ କରିବ ବୋଲି ଅନୁମାନ କରିଛି । ଏଥିପାଇଁ ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ରାଜଭବନ ପରିତ୍ୟାଗ କରି ଚାଲିଯିବା ପାଇଁ ନିର୍ଦ୍ଦେଶ ଦେଇଛି । ହେଲେ କେହି ତା’ କଥା ନ ଶୁଣିବାରୁ ସେ ଏକାକୀ ନିଜ କୁଳର କ୍ଷୟ ଦେଖୁବାକୁ ଇଚ୍ଛାନକରି ଦୁଃଖ୍ତମନା ହୋଇ ବନ ମଧ୍ଯକୁ ଚାଲିଯାଇଛି । ସେ ଯିବାପରେ ତା’ର ଅନୁମାନ ସତ୍ୟରେ ପରିଣତ ହୋଇଛି ଓ ବାନରକୁଳର ବିନାଶ ଘଟିଛି । ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ସ୍ବବଂଶର ବିନାଶ ଦେଖୁ ଗଭୀର ବିଷାଦମନା ହୋଇ ଅନାହାରରେ ବନକୁ ବନାନ୍ତର ଭ୍ରମଣ କରି ଅଧମ ରାଜାର ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେବାପାଇଁ ଚିନ୍ତାକରିଛି ।

ଏଥିରୁ ପ୍ରତୀୟମାନ ହୁଏ ଯେ ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ଅତ୍ୟନ୍ତ ବୁଦ୍ଧିମାନ୍ ଥିଲା । ବନ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ସେ ଏକ ସରୋବର ନିକଟରେ ପହଞ୍ଚିଛି । ସେଠାରେ ସେ ମନୁଷ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କର ଯିବାର ପାଦଚିହ୍ନ ଦେଖୁଛି ମାତ୍ର ଫେରିବାର ପାଦଚିହ୍ନ ଦେଖୁ ନପାରି ସେଠାରେ ଏକ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ କୁମ୍ଭୀର ଥିବାର ଅନୁମାନ କରି ଏକ ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ରେ ଜଳପାନ କରିଛି । ଏହା ଦେଖୁ ସରୋବରସ୍ଥ ରାକ୍ଷସ ରତ୍ନମାଳା ଧାରଣ କରି ପ୍ରତ୍ୟକ୍ଷ ହୋଇ ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ପ୍ରତି ସନ୍ତୋଷହୋଇ ବର ପ୍ରାର୍ଥନା କରିବାକୁ କହିଛି । ରାକ୍ଷସଠାରୁ ରତ୍ନମାଳା ନେଇ ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ ଲୋଭଦେଖାଇ ସପରିବାରେ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀକୁ ଅଣାଇଛି ଓ ଶେଷରେ ରାକ୍ଷସଦ୍ବାରା ଭକ୍ଷଣ କରାଇଛି । ଏହିପରିଭାବେ ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ନିଜର କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଜନିତ ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେଇଛି । ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ସହ ସେ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଆଚରଣ ହିଁ କରିଛି ।

ଶେଷରେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ବାନରଯୂଥପତିର ପ୍ରଶଂସା କରି କହିଛି –

“ ହତଃ ଶତଃ କୃତଂ ମିତ୍ର ରତ୍ନମାଳା ନ ହାରିତା ।

ନାଳେନାସ୍ୱାଦିତଂ ତୋୟଂ ସାଧୁ ଭୋ ବଟବାନର! ॥’’

ଅର୍ଥାତ୍ ହେ ବାନର ତୁମେ ଧନ୍ୟ ! ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ଜଳ ପିଇ ତୁମ ଶତ୍ରୁକୁ ବିନାଶ କରିଅଛ, ମୋତେ ମିତ୍ର କରିପାରିଛ ଓ ରତ୍ନମାଳାକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ହରାଇ ନାହିଁ । ବାନରଯୂଥପତିର ଏତାଦୃଶ ବୈଶିଷ୍ଟ୍ୟ ଅତ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଶିକ୍ଷଣୀୟ ହୋଇପାରିଛି ।

+2 1st Year Sanskrit Optional Chapter 4 ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିକଥା Summary

ଲେଖକ ପରିଚୟ – କଥାସାହିତ୍ୟର ଅମୂଲ୍ୟ ଗ୍ରନ୍ଥ ହେଉଛି ‘ପଞ୍ଚତନ୍ତ୍ର’ । ଏହାର ଲେଖକ ହେଉଛନ୍ତି ଉତ୍କଳୀୟ ବିଦ୍ୱାନ୍ ବିଷ୍ଣୁଶର୍ମା । ସେ ବ୍ରାହ୍ମଣ କୁଳରେ ଜନ୍ମିଥିଲେ । ରାଜା ଅମରଶକ୍ତିଙ୍କର ତିନୋଟି ପୁତ୍ରଙ୍କୁ ଛଅମାସ ମଧ୍ଯରେ ନୀତିଶାସ୍ତ୍ରରେ ଅଭିଜ୍ଞ କରିବାପାଇଁ ପ୍ରତିଶ୍ରୁତି ଦେଇଥିଲେ, ତଥା ପଶ୍ଚିତ କରାଇ ଦେଇଥିଲେ । ଏଥୁରୁ ତାଙ୍କର ଗଭୀର ପାଣ୍ଡିତ୍ୟର ପରିଚୟ ମିଳୁଛି । ତାଙ୍କର ସମୟ ପଞ୍ଚମ ବା ଷଷ୍ଠ ଶତାବ୍ଦୀ ବୋଲି ସମାଲୋଚକମାନେ ମତ ଦିଅନ୍ତି ଏବଂ ସେ ଓଡ଼ିଶାର ବିଦ୍ବାନ୍ ବୋଲି କହିଥା’ନ୍ତି । ସ୍ଵରଚିତ ଗ୍ରନ୍ଥରେ ଛାତ୍ରମାନଙ୍କୁ ଶିକ୍ଷାଦେବାର ଉପଯୁକ୍ତ କୌଶଳ ତାଙ୍କୁ ଜଣାଥିବାରୁ ସେ ଉତ୍ତମ ଶିକ୍ଷକରୂପେ ତଦାନୀନ୍ତନ ସମାଜରେ ସୁପରିଚିତ ଥିଲେ ।

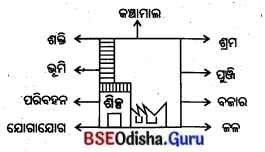

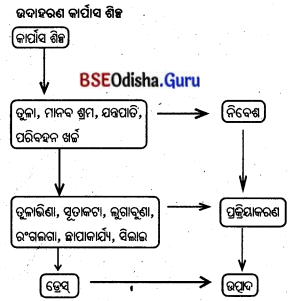

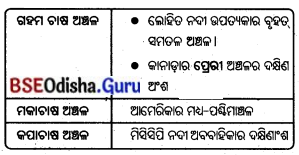

ବିଷୟ ପ୍ରବେଶ – ଆଲୋଚିତ ଗଳ୍ପଟି କଥାସାହିତ୍ୟ ‘ପଞ୍ଚତନ୍ତ୍ର’ର ଅଂଶବିଶେଷ । ୫ଟି ତନ୍ତ୍ର ବା ବିଭାଗକୁ ନେଇ ‘ପଞ୍ଚତନ୍ତ୍ର’ର ରଚନା କରାଯାଇଛି । ଏହି ପାଞ୍ଚଗୋଟି ବିଭାଗ ହେଲା –

- ମିତ୍ରଭେଦ

- ମିତ୍ରସଂପ୍ରାପ୍ତି

- କାକୋଲ୍ହ କୀୟ

- ଲବ୍ଧପ୍ରଣାଶ ଓ

- ଅପରୀକ୍ଷିତକାରକ।

‘ମିତ୍ରଭେଦ’ରେ ୨୨ ଗୋଟି, ‘ମିତ୍ରସଂପ୍ରାପ୍ତି’ରେ ୮ ଗୋଟି, ‘କାକୋଲ୍ କୀୟ’ରେ ୧୭ ଗୋଟି, ‘ଲବ୍ଧପ୍ରଣାଶ’ରେ ୧୪ ଗୋଟି ଓ ‘ଅପରୀକ୍ଷିତକାରକ’ରେ ୧୫ ଗୋଟି କାହାଣୀ ବିଦ୍ୟମାନ । ଏହି ଗ୍ରନ୍ଥରେ ଅତ୍ୟନ୍ତ ସରଳ ଭାଷାରେ ବିଭିନ୍ନ ପଶୁପକ୍ଷୀଙ୍କର କାହାଣୀ ମାଧ୍ୟମରେ ନୀତିଶିକ୍ଷା ପ୍ରଦାନ କରାଯାଇଅଛି । ଆଲୋଚିତ ‘ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିକଥା’ ‘ପଞ୍ଚତନ୍ତ୍ର’ର ପଞ୍ଚମ ତନ୍ତ୍ର ‘ଅପରୀକ୍ଷିତକାରକ’ର କାହାଣୀ ଯାହାର ପ୍ରାରମ୍ଭ ଏହିପ୍ରକାର କରାଯାଇଛି; ଯଥା – ଲୋକେ ଲୋଭଗ୍ରସ୍ତ ହେଲେ ବିଡ଼ମ୍ବିତ ହୋଇ କଷ୍ଟଭୋଗ କରିଥା’ନ୍ତି । କଥ୍ତ ଅଛି –

‘‘ଯୋ ଲୌଲ୍ୟାତ୍ କୁରୁତେ କର୍ମ ନୈବୋଦର୍କମବେକ୍ଷତେ ।

ବିଡ଼ମ୍ବନାମବାସ୍ତୋତି ସ ଯଥା ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତିଃ ।’’

ଅର୍ଥାତ୍ ଯେଉଁ ଲୋକ ଲୋଭପରବଶ ହୋଇ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟ କରେ ଓ ତା’ର ପରିଣାମ ବିଷୟରେ ଚିନ୍ତା କରେ ନାହିଁ, ସେ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ରଭୂପତି ପରି ବିଡ଼ମ୍ବନା ପ୍ରାପ୍ତ ହୁଏ ।

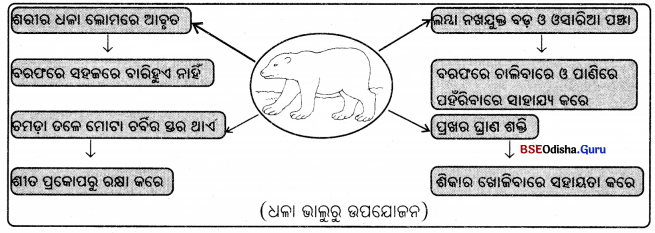

ସାରକଥା – ଗୋଟିଏ ନଗରରେ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ର ନାମକ ଜଣେ ରାଜା ବାସ କରୁଥିଲେ । ତାଙ୍କର ପୁତ୍ରମାନେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କ ସହିତ କ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରେ ରତ ରହୁଥିଲେ ଓ ସେମାନଙ୍କୁ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ଅନେକପ୍ରକାର ଖାଦ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ଦେଇ ପୁଷ୍ଟ କରୁଥିଲେ । ଏହି ବାନରୟୂଥର ଅଧୂପତି ଶୁକ୍ର, ବୃହସ୍ପତି ଓ ଚାଣକ୍ୟଙ୍କର ନୀତିଶାସ୍ତ୍ରମାନ ଜାଣିଥୁଲା ଓ ତଦନୁସାରେ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟ କରୁଥିଲା । ସେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଶିକ୍ଷା ଦେଉଥିଲା । ସେହି ରାଜପୁରୀରେ ଛୋଟ ରାଜକୁମାରମାନଙ୍କର ବାହନଯୋଗ୍ୟ ଗୋଟିଏ ମେଷପଲ ଥିଲା । ସେହି ମେଷପଲ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ଗୋଟିଏ ମେଷ ଜିହ୍ବାଲାଳସା ହେତୁରୁ ଦିବାରାତ୍ର ରନ୍ଧନଶାଳାରେ ପଶି ଯାହାକିଛି ଦେଖୁଥିଲା, ତାହା ଖାଇଯାଉଥିଲା । ପାଚକମାନେ କାଷ୍ଠ, ମୃତ୍ତିକାନିର୍ମିତ ପାତ୍ର, କାଂସ୍ୟପାତ୍ର ବା ତାମ୍ରପାତ୍ର ଯାହାକିଛି ପାଉଥିଲେ ସେଥିରେ ତାକୁ ପିଟୁଥିଲେ ।

ବାନରଯୂଥର ଅଧୂପତି ଏହା ଦେଖୁ ଚିନ୍ତା କରିବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲା – ଅହୋ, ମେଷ ଓ ପାଚକଙ୍କର ଏହି କଳହ ଶେଷରେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ବିନାଶର କାରଣ ହେବ । ଏ ମେଷଟି ଅନ୍ନଭୋଜନ ପାଇଁ ଲୋଲୁପ ଓ ପାଚକମାନେ ନିତାନ୍ତ କ୍ରୁଦ୍ଧ ହୋଇ ଯାହାକିଛି ନିକଟରେ ଦେଖୁଛନ୍ତି ସେଥୁରେ ତାକୁ ପିଟୁଛନ୍ତି । ଯଦି କେବେ ପାଖରେ ଅନ୍ୟ କିଛି ନପାଇ ପାଚକମାନେ ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଷ୍ଠଖଣ୍ଡରେ ତାକୁ ପ୍ରହାର କରନ୍ତି ତେବେ ମେଷର ଦେହରେ ଥିବା ପ୍ରଚୁର ଲୋମରେ ସାମାନ୍ୟ ଅଗ୍ନି ଲାଗିଲେ ମଧ୍ୟ ପ୍ରଜ୍ଜ୍ୱଳିତ ହୋଇଉଠିବ । ତା’ପରେ ସେ ନିକଟବର୍ତ୍ତୀ ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବ । ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରଚୁର ତୃଣ ଥିବାରୁ ତାହା ଜଳି ଉଠିବ । ଫଳରେ ଅଶ୍ଵମାନେ ଅଗ୍ନିରେ ପୋଡ଼ିଯିବେ । ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର ଅଶ୍ମଶାସ୍ତ୍ରରେ କହିଅଛନ୍ତି – ବାନରର ଚର୍ବିଦ୍ଵାରା ଅଶୁମାନଙ୍କର ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହ ପ୍ରଶମିତ ହୁଏ । ଏହିପରି ଦିନେ ଅବଶ୍ୟ ଘଟିବ । ଏକଥା ନିଶ୍ଚିତ ।

ଏହିପରି ବିଚାର କରି ସେ ବାନର ଯୂଥପତି ସବୁ ବାନରଙ୍କୁ ଡାକି ଏକାନ୍ତରେ କହିଲା –

ପାଚକମାନଙ୍କର ମେଷ ସହିତ ଯେଉଁ କଳହ ଚାଲିଛି, ତାହା ପରିଣାମରେ ଆମ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ଯେ କ୍ଷୟସାଧନ କରିବ ଏଥିରେ ସନ୍ଦେହ ନାହିଁ । ୧ ।

ଯେଉଁ ଗୃହରେ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ଅକାରଣରେ କଳହ ଲାଗିଥାଏ, ପ୍ରାଣ ରଖୁବାକୁ ଇଚ୍ଛା ଥିଲେ, ସେ ଗୃହକୁ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ଚାଲିଯିବା ଉଚିତ । ୨ ।

ଆହୁରି ମଧ୍ୟ – କଳହ ହେତୁ ଗୃହର, କୁବାକ୍ୟ ହେତୁ ବନ୍ଧୁତ୍ଵର, ଦୁଷ୍ଟରାଜାଙ୍କ ହେତୁରୁ ରାଜ୍ୟର ଓ କୁକର୍ମ ହେତୁରୁ ମନୁଷ୍ୟର ଯଶର ବିନାଶ ଘଟିଥାଏ । ୩ ।

ଅତଏବ ଆମ ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କର ବିନାଶ ହେବା ପୂର୍ବରୁ ଏ ରାଜନଅରକୁ ଛାଡ଼ି ବନକୁ ପଳାଇଯିବା । ତାହାର ଏହି ଅପ୍ରିୟ ବଚନ ଶୁଣି ମନ୍ଦୋଦ୍ଧତ ବାନରମାନେ ଉଚ୍ଚ ହାସ୍ୟ କରି କହିଲେ, ‘‘ଓ ! ବାର୍ଦ୍ଧକ୍ୟ ହେତୁରୁ ତୁମର ବୁଦ୍ଧି ବିଚଳିତ ହେଲାଣି । ସେଥିପାଇଁ ଏପରି କହୁଛ । କୁହାଯାଇଅଛି –

ବାଳକ ଓ ବୃଦ୍ଧ ଉଭୟଙ୍କର ମୁଖ ଦନ୍ତହୀନ; ଉଭୟଙ୍କ ମୁଖରୁ ସର୍ବଦା ଲାଳ ଝରୁଥାଏ । କୌଣସି ବିଷୟରେ ଏ ଦୁହିଁଙ୍କର ବିଶେଷତଃ ବୃଦ୍ଧର ବୁଦ୍ଧି ସ୍ତୁରେ ନାହିଁ । ୪ ।

ଏଠାରେ ସ୍ଵର୍ଗ ସମାନ ସୁଖଭୋଗ, ରାଜପୁତ୍ରମାନଙ୍କ ସ୍ୱହସ୍ତପ୍ରଦତ୍ତ ବିବିଧ ଅମୃତତୁଲ୍ୟ ଭୋଜ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ଆମେମାନେ ବନ ମଧ୍ୟରେ କଷାୟ, କଟୁ, ତିକ୍ତ, କ୍ଷାର, ରୁକ୍ଷ ଫଳ ଖାଇପାରିବୁ ନାହିଁ ।’’ ଏହାଶୁଣି ବାନରପତି ଅଶ୍ରୁପ୍ଲାବିତ ନେତ୍ରରେ କହିଲା – ଆରେ ରେ ମୂର୍ଖ ! ତୁମେମାନେ ଏ ସୁଖର ପରିଣାମ ଜାଣିପାରି ନାହଁ । ପାପକର୍ମର ରସାସ୍ଵାଦନ ସଦୃଶ ଏ ସୁଖର ପରିଣାମ ବିଷମୟ ହେବ । କୂଳର ବିନାଶ ମୁଁ ନିଜେ ଦେଖିପାରିବି ନାହିଁ । ମୁଁ ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନ ବନକୁ ଚାଲିଯାଉଛି । କୁହାଯାଇଛି – ମିତ୍ର ବିପଦଗ୍ରସ୍ତ ହେବା, ନିଜର ସ୍ଥାନ ଅନ୍ୟଦ୍ୱାରା ଉପୀଡ଼ିତ ହେବା, ଦେଶଭଙ୍ଗ, କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ – ଏସବୁ ଯେଉଁମାନେ ଦେଖନ୍ତି ନାହିଁ, ସେମାନେ ଧନ୍ୟ । ୫ ।

ଯୂଥପତି ଏହା କହି, ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରଙ୍କୁ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ବନକୁ ଚାଲିଗଲା ।

ସେ ଯିବାପରେ ଦିନେ ସେହି ମେଷଟି ରନ୍ଧନଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । ପାଚକ ଅନ୍ୟ କିଛି ନପାଇ ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଷ୍ଠଖଣ୍ଡରେ ତାକୁ ପ୍ରହାର କରିବାରୁ ସେ ଜ୍ଵଳନ୍ତ ଶରୀରରେ ଚିତ୍କାର କରି କରି ନିକଟବର୍ତ୍ତୀ ଅଶ୍ଵଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । ସେଠାରେ ସେ ତୃଣପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଭୂମିରେ ଲୋଟିବାରୁ ସର୍ବତ୍ର ଏପରି ବହ୍ନିଶିଖା ଉଠିଲା ଯେ କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ବ ଚକ୍ଷୁ ହରାଇ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ପଡ଼ିଲେ । କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ୱ ବନ୍ଧନ ଛିନ୍ନକରି ଅର୍ଦ୍ଧଦଗ୍ଧ ଶରୀରରେ ଫ୍ରେଷାରାବ କରି ଇତସ୍ତତଃ ଧାଇଁବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲେ । ଏହା ଫଳରେ ଲୋକମାନେ ବ୍ୟାକୁଳ ହୋଇପଡ଼ିଲେ ।

ଏହି ଅବସ୍ଥାରେ ରାଜା ବିଷଣ୍ଣ ହୋଇ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର ଶାସ୍ତ୍ରଜ୍ଞ ବୈଦ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କୁ ଡକାଇ କହିଲେ, ‘‘ଏହି ଅଶ୍ୱମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ବ୍ୟଥାର ଉପଶମ ପାଇଁ କୌଣସି ଉପାୟ କୁହନ୍ତୁ ।’’ ସେମାନେ ଶାସ୍ତ୍ର ଦେଖୁ କହିଲେ, ମହାରାଜ ! ଏ ବିଷୟରେ ଭଗବାନ୍ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର କହିଅଛନ୍ତି –

ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ହେଲେ ଅନ୍ଧକାର ଯେପରି ଦୂର ହୋଇଯାଏ, ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ମେଦଦ୍ବାରା ଅଶୁମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ରୋଗ ସେହିପରି ବିନଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇଯାଏ । ୬ ।

ତେଣୁ ଅତିଶୀଘ୍ର ଏହି ଚିକିତ୍ସା କରାଯାଉ, ଯେପରିକି ଅଶୁମାନେ ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହ ଯୋଗୁଁ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ନ ପଡ଼ନ୍ତି । ରାଜା ଏହା ଶୁଣି ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରଙ୍କୁ ବଧ କରିବାପାଇଁ ଆଦେଶ ଦେଲେ । ଅଧୂକ କହିବା ନିଷ୍ପ୍ରୟୋଜନ । ଯଷ୍ଟି, ପ୍ରସ୍ତର ପ୍ରଭୃତି ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ସମସ୍ତ ବାନର ନିହତ ହେଲେ ।

ବାନର ଯୂଥପତି ପୁତ୍ର, ପୌତ୍ର, ଭ୍ରାତୁଷ୍ଟୁତ୍ର, ଭାଗିନେୟ ପ୍ରଭୃତିଙ୍କର ମରଣ ବିଷୟ ଜାଣି ଗଭୀର ବିଷାଦରେ ମଗ୍ନହୋଇ ଅନାହାରରେ ରହି ବନରୁ ବନାନ୍ତର ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲା । ସେ ମନେ ମନେ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା, ମୁଁ ଏ ଅଧମ ରାଜାର ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେଇ କିପରି ତା’ର ଅନିଷ୍ଟସାଧନ କରିବି । କୁହାଯାଇଛି –

ଏ ସଂସାରରେ ଯେଉଁ ଲୋକ ଭୟ ହେତୁରୁ ଅଥବା ଲୋଭ ହେତୁରୁ ନିଜ ନିଜ କୁଳ ପ୍ରତି ଶତ୍ରୁର ଅତ୍ୟାଚାରକୁ ସହିଯାଏ, ସେ ପୁରୁଷମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ନିତାନ୍ତ ଅଧମ ଅଟେ । ୭ |

ଏହାପରେ ସେହି ବୃଦ୍ଧ ବାନର ପିପାସାକୁଳ ହୋଇ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରୁ କରୁ କମଳ ପରିପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଗୋଟିଏ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ନିକଟରେ ପହଞ୍ଚିଲା । ସେ ସୂକ୍ଷ୍ମଭାବରେ ନିରୀକ୍ଷଣ କରି ଦେଖୁଲା ଯେ ବନବାସୀ ମନୁଷ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କର ସରୋବରରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବାର ପଦଚିହ୍ନମାନ ଅଛି, କିନ୍ତୁ ଫେରି ଆସିବାର ପଦଚିହ୍ନ ନାହିଁ । ତହୁଁ ସେ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା – ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ନିଶ୍ଚୟ ଗୋଟିଏ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ କୁମ୍ଭୀର ଅଛି । ତେଣୁ ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ଆଣି ଦୂରରେ ରହି ସେହି ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ଜଳପାନ କରିବି । ସେହିପରି ଜଳପାନ କରନ୍ତେ ଗଳାରେ ରନ୍ଧମାଳା ପରିଧାନ କରିଥିବା ଗୋଟିଏ ରାକ୍ଷସ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ବାହାରି ଆସି କହିଲା, ଯେ କେହି ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀର ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରେ, ମୁଁ ତାକୁ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କରେ । କ

ିନ୍ତୁ ଏପରି କୌଣସି ଚତୁର ଲୋକ ନାହିଁ, ଯେ କି ତୁମ ଭଳି ଏ ଉପାୟରେ ଜଳପାନ କରିବ । ତେଣୁ ମୁଁ ତୁମ ଉପରେ ସନ୍ତୁଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇଅଛି । ମନର ଅଭିଳାଷ ଅନୁସାରେ ବର ପ୍ରାର୍ଥନା କର । ବାନର କହିଲା, ତୁମର ଭୋଜନ କରିବାର ଶକ୍ତି କେତେ ? ରାକ୍ଷସ ଉତ୍ତର ଦେଲା, ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲେ ଶତ, ସହସ୍ର, ଅୟୁତ, ଲକ୍ଷ ପ୍ରାଣୀଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଭୋଜନ କରିପାରିବି । ମାତ୍ର ବାହାରେ ଥିଲାବେଳେ ମୋତେ ସାମାନ୍ୟ ଶୃଗାଳ ମଧ୍ୟ ଅପମାନିତ କରିପାରେ । ବାନର କହିଲା, ଜଣେ ରାଜା ସହିତ ମୋର ଘୋର ଶତ୍ରୁତା ଅଛି । ଯଦି ତୁମେ ମୋତେ ତୁମର ଏହି ରହାରଟି ଦେବ, ତାହାହେଲେ ମୁଁ ମୋର କଥାଚାତୁରୀରେ ଲୋଭ ଦେଖାଇ ସେ ରାଜାକୁ ତା’ର ପରିବାର ସହିତ ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରାଇବି । ରାକ୍ଷସ ତାହାର ଏହି ଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟ ବାକ୍ୟ ଶୁଣି ରହାରଟି ଦେଇ କହିଲା, ହେ ମିତ୍ର ! ଯାହା ଉଚିତ ମନେକରୁଛ, ତାହା କର ।

ବାନର ମଧ୍ଯ ରହାରରେ ନିଜର କଣ୍ଠଦେଶକୁ ସୁଶୋଭିତ କରି ବୃକ୍ଷ ଓ ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦମାନଙ୍କ ଉପରେ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିବାରୁ ଲୋକେ ତାହାକୁ ଦେଖୁ ପଚାରିଲେ, ହେ ବାନର ଯୂଥପତି ! ତୁମେ ଏତେ କାଳ ହେଲା କେଉଁଠାରେ ଥିଲ ? ଏଡ଼େ ସୁନ୍ଦର ରନ୍ଥମାଳା କାହୁଁ ପାଇଲ ? ଏହାର ତେଜ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟକିରଣକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ତିରସ୍କାର କରୁଛି । ବାନର କହିଲା, ଗୋଟିଏ ଅରଣ୍ୟ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଏକ ଅତି ଗୁପ୍ତ ସରୋବର ଅଛି । ତାହାକୁ ସ୍ଵୟଂ କୁବେର ନିର୍ମାଣ କରିଅଛନ୍ତି । ରବିବାର ଦିନ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ସମୟରେ ଯଦି କେହି ଉକ୍ତ ସରୋବରରେ ବୁଡ଼ ପକାଏ ତେବେ ସେ କୁବେରଙ୍କ ପ୍ରସାଦରୁ ଏହିପରି ରମାଳାରେ କଣ୍ଠକୁ ସୁଶୋଭିତ କରି ଜଳରୁ ବାହାରିଆସେ ।

ଏହାପରେ ରାଜା ଏହା ଶୁଣିପାରି ସେହି ବାନରକୁ ଡାକି ପଚାରିଲେ, ହେ ଯୂଥାଧୂପ ! ଏ କଥା କ’ଣ ସତ୍ୟ ? ରନ୍ମାଳାରେ ପରିପୂର୍ଣ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ କେଉଁଠାରେ ଅଛି ? ବାନର କହିଲା, ହେ ପ୍ରଭୁ ! ପ୍ରତ୍ୟକ୍ଷରେ ମୋ ଗଳାରେ ପଡ଼ିଥିବା ଏହି ରନ୍ଥମାଳା ଦେଖୁ ଆପଣଙ୍କର ବିଶ୍ୱାସ ହେବ । ତେଣୁ ଯଦି ଆପଣଙ୍କର ରମାଳାର ପ୍ରୟୋଜନ ଥାଏ, ତାହାହେଲେ କାହାରିକୁ ମୋ ସଙ୍ଗେ ପଠାନ୍ତୁ ଯେ ଦେଖାଇଦେବି । ଏହା ଶୁଣି ରାଜା କହିଲେ, ସେପରି ହେଲେ ମୁଁ ନିଜେ ମୋର ସମସ୍ତ ପରିବାର ସହିତ ଯିବି । ତେବେ ଅନେକ ରନ୍ଧମାଳା ପାଇପାରିବୁ । ବାନର କହିଲା, ତାହାହିଁ କରନ୍ତୁ । ସେହିପରି କରାଯିବାରୁ ରନ୍ମାଳା ପାଇବା ଲୋଭରେ ରାଜାଙ୍କ ସହିତ ସବୁ ପତ୍ନୀ ଓ ଭୃତ୍ୟ ପ୍ରଭୃତି ଚାଲିଲେ । ରାଜା ଦୋଳାରେ ବସି ଗଲେ । ବାନରକୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ରାଜାଙ୍କ କ୍ରୋଡ଼ରେ ବସାଇ ଅତି ସୁଖରେ ପ୍ରୀତିପୂର୍ବକ ନିଆଗଲା । ତେଣୁ ଯଥାର୍ଥରେ କହ୍ଲାଯାଇଛି –

‘‘ହେ ତୃଷ୍ଣାଦେବି ! ତୁମକୁ ନମସ୍କାର । ତୁମେ ଧନବନ୍ତ ଲୋକକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ଅକରଣୀୟ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟରେ ନିୟୋଜିତ କରୁଛ; ଦୁର୍ଗମ ସ୍ଥାନରେ ମଧ୍ୟ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରାଉଅଛି’’ || ୮ ||

ପୁଣି ମଧ୍ୟ – ଯେ ଶତମୁଦ୍ରାର ଅଧିକାରୀ, ସେ ସହସ୍ର ପାଇବାକୁ ଲାଳାୟିତ । ଯାହାର ସହସ୍ରମୁଦ୍ରା ଅଛି ସେ ଲକ୍ଷମୁଦ୍ରା କାମନା କରୁଅଛି । ଯେ ଲକ୍ଷାଧୂପତି ସେ ରାଜ୍ୟ ଅଭିଳାଷ କରୁଅଛି ଓ ଯେ ରାଜପଦରେ ପ୍ରତିଷ୍ଠିତ ହୋଇଅଛି ସେ ସ୍ୱର୍ଗକାମନା କରୁଅଛି । ୯ ।

ଜରାକ୍ରାନ୍ତ ବ୍ୟକ୍ତିର କେଶ ଶୁକ୍ଳ ହୋଇଯାଏ, ଦନ୍ତଗୁଡ଼ିକ ଝଡ଼ିପଡ଼ନ୍ତି, ଚକ୍ଷୁ ଦୃଷ୍ଟିଶକ୍ତି ହରାଏ, କର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଶୁଣିପାରେ ନାହିଁ; କିନ୍ତୁ କେବଳ ତୃଷ୍ଣା ହିଁ ତରୁଣ ହେଉଥାଏ । ୧୦ ।

ଏହାପରେ ସେହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ନିକଟରେ ଉପସ୍ଥିତ ହୁଅନ୍ତେ ବାନର ପ୍ରଭାତ କାଳରେ ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ କହିଲା, ଏଠାରେ ଅଧେ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ହେଲାବେଳକୁ ଯେଉଁମାନେ ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତି, ସେମାନେ ସିଦ୍ଧିଲାଭ କରନ୍ତି । ତେଣୁ ସମସ୍ତେ ଏକ ସଙ୍ଗରେ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତୁ । ଆପଣ ପରେ ମୋ ସହିତ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବେ । ତାହାହେଲେ ମୁଁ ଆପଣଙ୍କୁ ପୂର୍ବଦୃଷ୍ଟ ସ୍ଥାନକୁ ନେଇ ପ୍ରଚୁର ରନ୍ଧମାଳା ଦେଖାଇଦେବି ।

ଏହାପରେ ଲୋକମାନେ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ସେ ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କୁ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କଲା । ସେମାନେ ଅନେକବେଳ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଜଳରୁ ନ ବାହାରିବାରୁ ରାଜା ବାନରକୁ କହିଲେ, ହେ ଯୂଥପତି ! ମୋର ଲୋକମାନେ ଏତେ ବିଳମ୍ବ କରୁଛନ୍ତି କାହିଁକି ? ଏହା ଶୁଣିଲାମାତ୍ରେ ବାନର ତତ୍କ୍ଷଣାତ୍ ଏକ ବୃକ୍ଷକୁ ଆରୋହଣ କରି ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ କହିଲା, ଆରେ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ରାଜା ! ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଥିବା ରାକ୍ଷସ ତୋର ପରିଜନମାନଙ୍କୁ ଖାଇସାରିଛି । ମୁଁ କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଜନିତ ବୈରସାଧନ କରିଛି । ଏବେ ଯାଆ । ତୁ ମୋର ପ୍ରଭୁ ଥୁଲୁ ବୋଲି ତୋତେ ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରାଇଲି ନାହିଁ । କଥାତ ଅଛି –

କେହି ଉପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ଯୁପକାର ଓ ଅପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ଯୁପକାର କରିବ; କେହି ହିଂସା କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତିହିଂସା କରିବ; ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ସହିତ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଆଚରଣ କରିବ । ଏଥିରେ ମୁଁ କୌଣସି ଦୋଷ ଦେଖିପାରୁ ନାହିଁ । ୧୧ ।

ତୁ ମୋର କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ କରିଥିଲୁ; ମୁଁ ସେହିପରି ତୋର କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ କଲି । ଏହା ଶୁଣି ରାଜା କୋପାବିଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇ ପାଦରେ ଚାଲି ଚାଲି ଯେଉଁ ମାର୍ଗରେ ଆସିଥିଲେ ସେହି ମାର୍ଗରେ ଫେରିଗଲେ। ରାଜା ଚାଲିଯିବା ପରେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ତୃପ୍ତ ହୋଇ ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ବାହାରି ଆନନ୍ଦରେ କହିଲା –

ହେ ବାନର ତୁମେ ଧନ୍ୟ ! ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ଜଳ ପିଇ ତୁମ ଶତ୍ରୁକୁ ବିନାଶ କରିଅଛ; ମୋତେ ମିତ୍ର କରିପାରିଛ ଓ ରନ୍ଥମାଳାକୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ହରାଇ ନାହଁ । ୧୨ ।

Text – 1

कस्मिंश्चिन्नगरे ……………………………….. तेनाशु ताड़यन्ति।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – କବିଂଶ୍ଚିନ୍ନଗରେ = କୌଣସି ଏକ ନଅରରେ । ଭୂପତିଃ = ରାଜା । ବାନରକ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରତା = ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କ ସହ କ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରତ । ବାନରଯୂଥମ୍ = ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ପଲକୁ । ନିତ୍ୟମ୍ = ପ୍ରତିଦିନ । ପୁଷ୍ଟିମ୍ = ପୋଷଣ । ଅଥ = ଏହାପରେ । ବାନରଯୂଥାଧୂପ = ବାନରଦଳପତି । ଔଶନସମ୍ = ଶୁକ୍ର । ବାର୍ହସ୍ପତ୍ୟମ୍ = ବୃହସ୍ପତିପ୍ରଣୀତ ଧର୍ମଶାସ୍ତ୍ର । ଅଧ୍ୟାପୟତି ସ୍ମ = ପଢ଼ାଉଥିଲେ । ରାଜଗୃହେ = ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦରେ । ଲଘୁ = ହ୍ରସ୍ଵ ବା ଛୋଟ । ମେଷଯୂଥମ୍ = ମେଣ୍ଢାପଲ । ଜିହ୍ବାଲୌଲ୍ୟାତ୍ = ଭୋଜନ ଲୋଭରୁ । ଅହର୍ନିଶମ୍ = ଦିନରାତି । ନିଃଶଙ୍କମ୍ = ବିନା ଭୟରେ ବା ନିର୍ଭୟରେ । ମହାନସେ = ରୋଷଶାଳାରେ । ଯତ୍ = ଯାହା । ସୂପକାରା ରୋଷେଇଆମାନେ । ମୃଣ୍ମୟମ୍ = ମାଟିର । ଭାଜନମ୍ = ପାତ୍ର । ଆଶୁ = ଶୀଘ୍ର । ତାଡ଼ୟନ୍ତି = ମାରନ୍ତି ବା ପିଟନ୍ତି ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – କୌଣସି ଏକ ନଗରରେ ଚନ୍ଦ୍ର ନାମକ ଜଣେ ରାଜା ବାସ କରୁଥିଲେ । ତାଙ୍କର ପୁତ୍ରମାନେ ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କ ସହ କ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରତ ରହୁଥିଲେ ଓ ସେମାନଙ୍କୁ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ଅନେକପ୍ରକାରର ଖାଦ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ଦେଇ ପରିପୁଷ୍ଟ କରୁଥିଲେ । ଏହାପରେ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ଦଳପତି ଯିଏକି ଶୁକ୍ର, ବୃହସ୍ପତି ଓ ଚାଣକ୍ୟଙ୍କର ନୀତିଶାସ୍ତ୍ରମାନ ଜାଣିଥିଲା ଓ ତାକୁ ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଶିଖାଉଥିଲା । ଏହାପରେ ସେହି ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦରେ ଛୋଟ ରାଜକୁମାରମାନଙ୍କର ବାହନଯୋଗ୍ୟ ଏକ ମେଣ୍ଢାପଲ ଥିଲା । ସେମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ଏକ ମେଣ୍ଢା ଜିହ୍ବାଲାଳସା ହେତୁରୁ ଦିନରାତି ରନ୍ଧନଶାଳାରେ ପଶି ଯାହା ଦେଖୁଥିଲା ତାହାସବୁ ଖାଇଯାଉଥିଲା । ସେହି ରୋଷେଇଆମାନେ କାଷ୍ଠ, ମାଟିପାତ୍ର, କଂସାପାତ୍ର ବା ତମ୍ବାପାତ୍ର ଯାହାକିଛି ପାଉଥିଲେ ସେଥିରେ ତାକୁ ଶୀଘ୍ର ପିଟୁଥିଲେ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – କଟିଂଷ୍ଟିନ୍ନଗରେ = କସ୍ମିନ୍ + ଚିତ୍ + ନଗରେ । ନିତ୍ୟମେବାନେକଭୋଜନଭର୍ଯ୍ୟାଦିର୍ଭି = ନିତ୍ୟମ୍ + ଏବ + ଅନେକଭୋଜନଭକ୍ଷ୍ୟ + ଆଦିଭିଂ । ବାନରଯୂଥାଧୂପଃ = ବାନରଯୂଥ + ଅଧ୍ୟାପଃ । ମତବିତ୍ତଦନୁଷ୍ଠାତା = ମତବିତ୍ + ତତ୍ + ଅନୁଷ୍ଠାତା । ସର୍ବାନପ୍ୟଧ୍ୟାପୟତି = ସର୍ବାନ୍ + ଅପି + ଅଧ୍ୟାପୟତି । ମେଷଯୂଥମସ୍ତି = ମେଷଯୂଥମ୍ + ଅସ୍ତି । ତନ୍ମଧାଦେକ = ତତ୍ + ମଧ୍ୟାତ୍ + ଏକଃ । ଜିହ୍ବାଲୌଲ୍ୟାଦହର୍ନିଶମ୍ = ଜିହ୍ବାଲୌଲ୍ୟାତ୍ + ଅହର୍ନିଶମ୍ । ତେନାଶୁ = ତେନ + ଆଶୁ ।

ସମାସ – ଭୂପତିଃ = ଭୁନଃ ପତିଃ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ବାନରକ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରତଃ = ବାନରଃ କ୍ରୀଡ଼ାରତା (୩ୟା ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ବାନରଯୂଥମ୍ = ବାନରାମାଂ ଯୂଥମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ବାନରଯୂଥାଧୂପଃ = ବାନରାଣା ଯୂଥମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ତସ୍ୟ ଅଧୂପ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ରାଜଗୃହେ = ରାଜ୍ଞ ଗୃହମ୍, ତସ୍ମିନ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ଜିହ୍ଵାଲୌଲ୍ୟାତ୍ = ଜିହ୍ବାୟା ଲୌଲ୍ୟମ୍, ତସ୍ମାତ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ଅହର୍ନିଶମ୍ = ଅହଃ ଚ ନିଶା ଚ (ଇତରେତର ବୃଦଃ) । ସୂପକାରା = ସୂପଂ କରୋତି ଇତି, ତେ (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । କାଂସ୍ୟପାତ୍ରମ୍ = କାଂସ୍ୟ ନିର୍ମିତଂ ପାତ୍ରମ୍ (ମଧ୍ୟପଦଲୋପୀ କର୍ମଧାରୟ) । ତାମ୍ରପାତ୍ରମ୍ = ତାମ୍ର ନିର୍ମିତଂ ପାତ୍ରମ୍ (ମଧ୍ୟପଦଲୋପୀ କର୍ମଧାରୟ)।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ଚନ୍ଦ୍ର = ନାମ ଅବ୍ୟୟ ଯୋଗେ ୧ମା । ଭୂପତିଃ, ପୁତ୍ରା, ଯଃ, ସ, ମେଷଯୂଥମ୍, ଏକଃ, ତେ, ସୂପକାରା = କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ପୁଷ୍ଟି, ତାନ୍, ସର୍ବାନ୍, ସର୍ବଂ, କାଷ୍ଠ, ମୃଣ୍ମୟଭାଜନଂ, କାଂସ୍ୟପାତ୍ର, ତାମ୍ରପାତ୍ରମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଅନେକଭୋଜନଭର୍ଯ୍ୟାଦିଭି, ତେନ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ତନ୍ମଧ୍ୟାତ୍ = ଅପାଦାନେ ୫ମୀ । ଜିହ୍ବାଲୌଲ୍ୟାତ୍ = ହେତୌ ୫ମୀ। ତସ୍ୟ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ନଗରେ, ତସ୍ମିନ୍, ରାଜଗୃହେ, ମହାନସେ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ପୁଷ୍ଟିମ୍ = ପୂଷ୍ + ଭିନ୍ । ପ୍ରବିଶ୍ୟ = ପ୍ର + ବିଶ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍।

Text – 2

सोऽपि वानरयूथपस्तद् ………………………….. रहसि प्रोवाच।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଅପି = ମଧ୍ୟ । ବାନରଯୂଥପ = ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ଦଳପତି । ଦୃଷ୍ଟା = ଦେଖୁ । ବ୍ୟଚିନ୍ତୟତ୍ = ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା । କ୍ଷୟାୟ = ନାଶ ନିମନ୍ତେ । ଲମ୍ପଟ = ଆସକ୍ତ । ମେଷ = ମେଣ୍ଢା । ମହାକୋପା = ମହାରାଗୀ । ପ୍ରହରନ୍ତି = ପିଟନ୍ତି । ଆସନ୍ତ = ସମୀପବର୍ତୀ । ଉଲ୍ଲେ କେନ = ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଠଖଣ୍ଡଦ୍ବାରା । ଭଣ୍ଡା = ଲୋମ । ବହ୍ନିନା = ଅଗ୍ନିଦ୍ଵାରା । ଦସ୍ୟମାନଃ = ଜଳୁଥିବା। କୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ = କୁଟୀରକୁ । ତତଃ = ତାହାପରେ । ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରେଣ = ଅଶ୍ଵଚିକିତ୍ସକଦ୍ବାରା । ପୁନଃ = ପୁଣି । ବସୟା = ମାଂସଜାତ ଦେହସ୍ଥ ଧାତୁ ବିଶେଷଦ୍ଵାରା । ପ୍ରଶାମ୍ୟତି = ଶାନ୍ତ ହେବ । ନୂନମ୍ = ନିଶ୍ଚୟ । ଏବମ୍ = ଏହିପରି । ସର୍ବାନ୍ = ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କୁ । ଆହୂୟ = ଡାକି । ରହସି = ଏକାନ୍ତରେ । ପ୍ରୋବାଚ = କହିଲା ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ସେହି ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କର ଦଳପତି ମଧ୍ୟ ତାହା ଦେଖୁ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା, ଆହେ ! ମେଣ୍ଢା ଓ ପାଚକମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ଏହି କଳହ ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କର ବିନାଶର ନିମିତ୍ତ ହେବ, ଯେହେତୁ ଏହି ମେଣ୍ଟାଟି ଅନ୍ନାସ୍ବାଦ ନିମନ୍ତେ ଆସକ୍ତ ଏବଂ ପାଚକମାନେ ଅତ୍ୟନ୍ତ କ୍ରୂର ବା କ୍ରୋଧୀ, ଯେକୌଣସି ବସ୍ତୁଦ୍ବାରା ପିଟିପାରନ୍ତି । ଯଦି କେବେ କୌଣସି ବସ୍ତୁ ଅଭାବରୁ ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଠଖଣ୍ଡଦ୍ୱାରା ବାଡ଼େଇବେ ତେବେ ପ୍ରଚୁର ଲୋମଯୁକ୍ତ ଏହି ମେଣ୍ଟାଟି ଅତିଅଳ୍ପ ଅଗ୍ନିଦ୍ଵାରା ମଧ୍ୟ ପ୍ରଜ୍ଜ୍ୱଳିତ ହୋଇଉଠିବ । ତାହା ଜ୍ବଳମାନ ହୋଇ ପୁନଶ୍ଚ ଘୋଡ଼ାଶାଳା ନିକଟରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବ । ଘୋଡ଼ାଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରଚୁର ଘାସ ଥିବାରୁ ତାହା ଜଳିଉଠିବ । ଫଳରେ ଘୋଡ଼ାମାନେ ନିଆଁରେ ପୋଡ଼ିଯିବେ । ଅଶୁମାନଙ୍କର ଚିକିତ୍ସକ (ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର)ଙ୍କଦ୍ୱାରା ପୁଣି ଏହା କୁହାଯାଇଛି ଯେ, ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କର ବସାଦ୍ୱାରା (ମାଂସାଶ୍ରିତ ଦେହସ୍ଥ ଧାତୁବିଶେଷ) ଘୋଡ଼ାମାନଙ୍କର ଅଗ୍ନିଜନିତ ଜ୍ଵଳନଦୋଷ ଶାନ୍ତ ହେବ ବା ପ୍ରଶମିତ ହେବ । ତେଣୁ ଏହିପରି ଦିନେ ଅବଶ୍ୟ ଘଟିବ । ଏହିପରି ନିଶ୍ଚିତ କରି (ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କର ଦଳପତି) ସମସ୍ତ ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କୁ ଡାକି ଏକାନ୍ତରେ କହିଲା।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ସୋଽପି = ନଃ + ଅପି । ବାନରଯୂଥପସ୍ତଦ୍ = ବାନରଯୂଥପଃ + ତଦ୍ । ବ୍ୟଚିନ୍ତୟତ୍ = ବି + ଅଚିନ୍ତୟତ୍ । ମେଷସୂପକାରକଳହୋଽୟମ୍ = ମେଷସୂପକାରକଳହଃ + ଅୟମ୍ । ଯତୋଽସ୍ବାଦଲମ୍ପଟୋଽୟମ୍ = ଯତଃ + ଅନ୍ନ + ଆସ୍ବାଦଲମ୍ପରଃ + ଅୟମ୍ । ମହାକୋପାଣ୍ଡ = ମହାକୋପଃ + ଚ । ଯଥାସନ୍ନବସ୍ତୁନା = ଯଥା + ଆସନ୍ନବସ୍ତୁନା । ବସ୍ତୁନୋଽଭାବାତ୍ = ବସ୍ତୁନଃ + ଅଭାବାତ୍ । କଦାଚିଦୁଲୁ କେନ = କଦାଚିତ୍ + ଉଲ୍ଲେ କେନ । ତଦୋଣ୍ଡାପ୍ରଚୁରୋଽୟମ୍ = ତଦା + ଭଣ୍ଡାପ୍ରଚୁରଃ + ଅୟମ୍ । ସ୍ଵଜେନାପି = ସ୍ଵନ + ଅପି । ତଦ୍ଦନ୍ଦ୍ୟମାନଃ = ତତ୍ + ଦସ୍ୟୁମାନଃ । ପୁନରଶୁକୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ = ପୁନଃ + ଅଶ୍ଵକୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ । ସାପି = ସା + ଅପି । ତୃଣପ୍ରାଚୁର୍ଯ୍ୟାଜ୍ବଳିଷ୍ୟତି = ତୃଣପ୍ରାଚୁର୍ଯ୍ୟାତ୍ + ଜ୍ଜ୍ବଳିଷ୍ୟତି । ତତୋଽଶ୍ୱ = ତତଃ + ଅଶ୍ୱା । ବହ୍ନିଦାହମବାପ୍ସ୍ୟନ୍ତି = ବହ୍ନିଦାହମ୍ + ଅବାପ୍ସ୍ୟନ୍ତ । ପୁନରେତଦୁକ୍ତମ୍ = ପୁନଃ + ଏତତ୍ + ଉକ୍ତମ୍ । ଯଦ୍ମାନରବସୟା = ଯତ୍ + ବାନରବସୟା । ତନ୍ତୁନମେତନ = ତତ୍ + ନୂନମ୍ + ଏତେନ । ଭାବ୍ୟମିତ୍ର = ଭାବ୍ୟମ୍ + ଅତ୍ର । ନିଶ୍ଚୟ = ନିଃ + ଚୟ । ବାନରାନାହ୍ୟ = ବାନରାନ୍ + ଆହୂୟ । ପ୍ରୋବାଚ = ପ୍ର + ଉବାଚ।

ସମାସ – ମେଷସୂପକାରକଳହଃ = ମେଷ ଚ ସୂପକାରଃ ଚ (ଦ୍ବଦୁଃ) ତ କଳହଃ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ମହୋକୋପା = ମହାନ୍ କୋପଃ, ତେ (କର୍ମଧାରୟ) । ଅଶ୍ଵକୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ = ଅଶ୍ୱିନାଂ କୁଟୀ, ତସ୍ୟାମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ବହ୍ନିଦାହମ୍ = ବହ୍ନିନା ଦାହମ୍ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ବାନରବସୟା = ବାନରାମାଂ ବସା, ତୟା (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ)।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ବାନରଯୂଥପଃ, ଅୟଂ, ମେଷ, ସୂପକାରାଃ, ମହାକୋପା, ଉଶ୍ୱପ୍ରଚୁରଃ, ଦସ୍ୟମାନଃ, ଅଶ୍ୱ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ଏତତ୍, ବହ୍ନିଦାହଦୋଷ = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧ ମା । ସା = ଅପି ଅବ୍ୟୟ ଯୋଗେ ୧ମା । ଅହୋ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମ । ବହ୍ନିଦାହମ୍, ସର୍ବାନ୍, ବାନରାନ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଆସନ୍ନବସ୍ତୁନା, ଉଲୁ କେନ, ସ୍ଵନ, ବହ୍ନିନା, ଏତେନ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରେଣ, ବାନରବସୟା = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । କ୍ଷୟାୟ = ନିମିତ୍ତାର୍ଥେ ୪ର୍ଥୀ । ଅଭାବାତ୍, ତୃଣପ୍ରାଚୁର୍ଯ୍ୟାତ୍ = ହେତେ ୫ମୀ । ବାନରାଣା, ବସ୍ତୁନଃ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ଅଶ୍ଵକୁଟିଂ, ସମୀପବର୍ଜିନ୍ୟାମ୍ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଦୃଷ୍ଟି = ଦୃଶ୍ + ଷ୍ଟ୍ରାଚ୍ । ଆସନ୍ନ = ଆ + ସଦ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଦଶ୍ୟମାନଃ = ଦହ୍ + ଶାନବ । ଉକ୍ତମ୍ = ବଚ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଦୋଷ = ଦୁଷ୍ + ଘଞ୍ଚ୍ ନିଶ୍ଚିତ୍ୟ = ନିଃ + ଚି + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍।

Text – 3

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

यत्-

मेषेण सूपकाराणां कलहो यत्र जायते।

स भविष्यत्यसंदिग्धं वानराणां क्षयावहः ॥ १ ॥

ଯତ୍ –

ମେଷେଣ ସୂପକାରାଣା କଳହୋ ଯତ୍ର ଜାୟତେ ।

ସ ଭବିଷ୍ୟତ୍ୟସଂଦିଗ୍ଧ ବାନରାମାଂ କ୍ଷୟାବହିଃ ॥ ୧ ||

ଅନ୍ବୟ – ସୂପକାରାମାଂ ମେଷେଣ କଳତଃ ଯତ୍ର ଜାୟତେ, ସ୍ୱ ବାନରାଣା କ୍ଷୟାବହିଃ ଭବିଷ୍ୟତି (ଅତ୍ର) ଅସଂଦିଗ୍ମ୍ । ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ସୂପକାରାଣାମ୍ = ପାଚକମାନଙ୍କର । ମେଷେଣ ମେଷ ସହିତ । କଳତଃ = କଳି । ଯତ୍ର = ଯେଉଁଠି । ଜାୟତେ = ଜାତ ହୋଇଛି ବା ଚାଲିଛି । ବାନରାଣାମ୍ = ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର । କ୍ଷୟାବହିଃ = କ୍ଷୟସାଧନ । ଅସଂଦିଗ୍ଧର୍ମ = ଏଥିରେ ସନ୍ଦେହ ନାହିଁ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଯେଣୁ ପାଚକମାନଙ୍କର ମେଷ ସହିତ ଯେଉଁ କଳହ ଚାଲିଛି, ତାହା ପରିଣାମରେ ଆମ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ଯେ କ୍ଷୟସାଧନ କରିବ ଏଥିରେ ସନ୍ଦେହ ନାହିଁ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – କଳହୋ ଯତ୍ର = କଳହଃ + ଯତ୍ର । ଭବିଷ୍ୟତ୍ୟସଂଦିଗ୍ଧମ୍ = ଭବିଷ୍ୟତି + ଅସଂଦିଗ ଧମ୍ । କ୍ଷୟାବହିଃ = କ୍ଷୟ + ଆବହିଃ ।

ସମାସ – ଅସଂଦିଗ୍ଧମ୍ = ନ ସଂଦିଗ୍ଧମ୍ (ନତ୍ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । କ୍ଷୟାବହିଃ = କ୍ଷୟମ୍ ଆବହତି ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣ ବିଭକ୍ତି – ସ୍ୱ, କଳତଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ସୂପକାରାଣା, ବାନରାଣାମ୍ = ଶେଷ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ମେଷେଣ = ସହାର୍ଥେ ୩ୟା ।

Text – 4

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

तस्मात्स्यात् कलहो यत्र गृहे नित्यमकारणः।

तद्गृहं जीवितं वाञ्छन् दूरतः परिवर्जयेत् ॥ २ ॥

ତସ୍ମାସ୍ୟାତ୍ କଳହୋ ଯତ୍ର ଗୃହେ ନିତ୍ୟମକାରଣ ।

ତଦ୍ଗୃହଂ ଜୀବିତଂ ବାଞ୍ଛନ୍ ଦୂରତଃ ପରିବର୍ଜୟେତ୍ ॥ ୨ ||

ଅନ୍ବୟ – ତସ୍ମାତ୍ ଯତ୍ର ଗୃହେ ନିତ୍ୟମ୍ ଅକାରଣଂ କଳତଃ ସ୍ୟାତ୍ । ଜୀବିତଂ ବାଞ୍ଛନ୍ (ନରଃ) ତଦ୍ଗୃହଂ ଦୂରତଃ ପରିବର୍ଜୟେତ୍ । ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ତସ୍ମାତ୍ = ସେହି ହେତୁରୁ । ଯତ୍ର = ଯେଉଁଠାରେ । ଗୃହେ = ଘରେ । ନିତ୍ୟମ୍ = ପ୍ରତିଦିନ । ଅକାରଣ = ବିନା କାରଣରେ । ସ୍ୟାତ୍ = ହୋଇପାରେ । ଜୀବିତମ୍ = ଜୀବନ । ବାଞ୍ଛନ୍ = ଇଚ୍ଛା ଥିଲେ । ତଦ୍ଗୃହମ୍ = ସେହି ଘରକୁ । ଦୂରତଃ = ଦୂରରୁ । ପରିବର୍ଜୟେତ୍ = ପରିତ୍ୟାଗ କରିବା ଉଚିତ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ସେହେତୁ ଯେଉଁ ଗୃହରେ ପ୍ରତିଦିନ ଅକାରଣରେ କଳହ ଲାଗିଥାଏ, ପ୍ରାଣ ରଖୁବାକୁ ଇଚ୍ଛା ଥିଲେ, ସେ ଗୃହକୁ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ଚାଲିଯିବା ଉଚିତ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ତସ୍ମାସ୍ୟାତ୍ = ତସ୍ମାତ୍ + ସ୍ୟାତ୍ । କଳହୋ ଯତ୍ର = କଳହଃ + ଯତ୍ର । ନିତ୍ୟମକାରଣ = ନିତ୍ୟମ୍ + ଅକାରଣ । ତଦ୍ଗୃହମ୍ = ତତ୍ + ଗୃହମ୍ ।

ସମାସ – ଅକାରନଃ = ନ କାରଣ (ନଵ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ତଦ୍ଗୃହମ୍ = ତସ୍ୟ ଗୃହମ୍, ତତ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ତସ୍ମାତ୍ = ହେତୌ ୫ମୀ । ଗୃହେ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ । ଅକାରନଃ, କଳହଃ କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ଜୀବିତଂ, ବାଞ୍ଛନ୍ = କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ତଦ୍ଗୃହମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଦୂରତଃ = ଅପାଦାନେ ୫ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଜୀବିତମ୍ = ଜୀବ୍ + ଶତ୍ରୁ । ବାଞ୍ଛନ୍ = ବାଞ୍ଚ୍ + ଶତୃ ।

Text – 5

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

तथा च-

कलहान्तानि हर्म्याणि कुवाक्यान्तं च सौहृदम्।

कुराजान्तानि राष्ट्राणि कुकर्मान्तं यशो नृणाम् ॥ ३॥

ତଥା ଚ-

କଳହାନ୍ତାନି ହର୍ମାଣି କୁବାକ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଚ ସୌହୃଦମ୍ ।

କୁରାଜାନ୍ତାନି ରାଷ୍ଟ୍ରାଣି କୁକର୍ମାନ୍ତ ଯଶୋ ନୃଣାମ୍ ॥ ୩ ॥

ଅନ୍ବୟ – କଳହାନ୍ତାନି ହର୍ମାଣି କୁବାକ୍ୟାନ୍ତ ସୌହୃଦଂ କୁରାଜାନ୍ତାନି ରାଷ୍ଟ୍ରାଣି, କୁକର୍ମାନ୍ତ ନୃଣା ଯଶଃ ଚ (ବିନଶ୍ୟତି) । ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ହର୍ମାଣି = ଗୃହମାନ । ସୌହୃଦମ୍ = ବନ୍ଧୁତ୍ଵ । ରାଷ୍ଟ୍ରାଣି = ରାଜ୍ୟମାନ । ନୃଣାମ୍ = ମନୁଷ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କର । ଯଶଃ = କୀର୍ତି ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – କଳହ ହେତୁ ଗୃହର, କୁବାକ୍ୟ ହେତୁ ବନ୍ଧୁତ୍ଵର, ଦୁଷ୍ଟରାଜାଙ୍କ ହେତୁରୁ ରାଜ୍ୟର ଓ କୁକର୍ମ ହେତୁରୁ ମନୁଷ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କ ଯଶର ବିନାଶ ଘଟିଥାଏ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – କଳହାନ୍ତାନି = କଳହ + ଅନ୍ତାନି । କୁବାକ୍ୟାନ୍ତମ୍ = କୁବାକ୍ୟ + ଅନ୍ତମ୍ଭ । କୁରାଜାନ୍ତାନି = କୁରାଜ + ଅନ୍ତାନି । କୁକର୍ମାନ୍ତମ୍ = କୁକର୍ମ + ଅନ୍ତମ୍ । ଯଶୋନ୍ଧଣାମ୍ = ଯଶଃ + ନୃଣାମ୍ ।

ସମାସ – କୁବାକ୍ୟମ୍ = କୁତ୍ସିତଂ ବାକ୍ୟମ୍ (କର୍ମଧାରୟ) । କୁକର୍ମ = କୁତ୍ସିତ କର୍ମ (କର୍ମଧାରୟ) । କୁରାଜା କୁତ୍ସିତ ରାଜା (କର୍ମଧାରୟ ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – କଳହାନ୍ତାନି, ହର୍ମାଣି, କୁରାଜାନ୍ତାନି, ରାଷ୍ଟ୍ରାଣି = କର୍ଭରି ୧ମା । ସୌହୃଦମ୍, ଯଶଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ନୃଣାମ୍ = ଶେଷ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ ।

Text – 6

तन्न यावत् सर्वेषां …………………………….. ये नैतद्ब्रवीषि।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଯାବତ୍ = ଯେ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ । ସର୍ବେଷାମ୍ = ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କର । ସଂକ୍ଷୟ = ବିନାଶ । ତାବତ୍ = ସେ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ । ସଂତ୍ୟଜ୍ୟ = ସଂପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ତ୍ୟାଗକରି । ବନମ୍ = ବଣକୁ । ଅଥ = ଏହାପରେ । ବଚନମ୍ = କଥାକୁ । ଅଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟମ୍ = ଅପ୍ରିୟ । ଶୁଦ୍ୱା = ଶୁଣି । ମଦୋଦ୍ଧତା = ଦୁଷ୍ଟପ୍ରବୃତ୍ତିଯୁକ୍ତ । ପ୍ରହସ୍ୟ = ହସି ହସି । ପ୍ରୋଚୁ = କହିଲା । ବୁଦ୍ଧିବୈକଲ୍ୟାମ୍ = ବୁଦ୍ଧି ବିଚଳିତ । ସଂଜାତମ୍ = ହୋଇଅଛି ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ତେଣୁ ଯେପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ସମସ୍ତଙ୍କର ବିନାଶ ନ ହୋଇଛି ସେ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଏହି ରାଜଗୃହକୁ ପରିତ୍ୟାଗ କରି ବଣକୁ ଚାଲିଯିବା । ଏହାପରେ ତାହାର ଏହି ଅପ୍ରିୟ ବଚନ ଶୁଣି ମନ୍ଦୋଦ୍ଧତ ବାନରମାନେ ଉଚ୍ଚସ୍ୱରରେ ହସି କହିଲେ – ଆହେ ! ତୁମର ବୃଦ୍ଧତ୍ଵ ହେତୁ ବୁଦ୍ଧି ବିଚଳିତ ହୋଇଅଛି ଯଦ୍ବାରା ଏପରି କହୁଅଛି ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ତନ୍ତ୍ର = ତତ୍ + ନ । ତାବଦେତଦ୍ରାଜଗୃହମ୍ = ତାବତ୍ + ଏତତ୍ + ରାଜଗୃହମ୍ । ତତ୍ତସ୍ୟ = ତତ୍ + ତସ୍ୟ । ବଚନମଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟମ୍ = ବଚନମ୍ + ଅଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟମ୍ । ପ୍ରୋତୁଃ = ପ୍ର + ଉ । ଯେନୈତଦ୍ବ୍ରବୀର୍ଷି = ଯେନ + ଏତତ୍ + ବ୍ରବୀଷି ।

ସମାସ – ସଂକ୍ଷୟ = ସମ୍ୟକ୍ କ୍ଷୟ (ପ୍ରାଦି ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ରାଜଗୃହମ୍ = ରାଜ୍ଞ ଗୃହଂ, ତମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ଅଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟମ୍ = ନ ଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟମ୍ (ନୡ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ମନ୍ଦୋଦ୍ଧତା = ମଦେନ ଉଦ୍ଧତଃ, ତେ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ବୃଦ୍ଧଭାବାତ୍ = ବୃଦ୍ଧସ୍ୟ ଭାବ, ତସ୍ମାତ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ବୁଦ୍ଧିବୈକଲ୍ୟାମ୍ = ବୁଦ୍ଧେ ବୈକଲ୍ୟମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ସଂକ୍ଷୟ, ମଦୋଦ୍ଧତା, ବାନରା = କର୍ଭରି ୧ ମା । ଭୋ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ରାଜଗୃହଂ, ବନଂ, ବଚନଂ, ଅଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଯେନ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ବୃଦ୍ଧଭାବାତ୍ = ହେତୌ ୫ମୀ । ସର୍ବେଷା, ତସ୍ୟ, ଭବତଃ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତି ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ସଂତ୍ୟଜ୍ୟ = ସମ୍ + ତ୍ୟଜ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ବଚନମ୍ = ବଚ୍ + ଲ୍ୟୁଟ୍ । ଶୁଡ଼ା = ଶୁ + ସ୍କାଚ୍ । ପ୍ରହସ୍ୟ = ପ୍ର + ହସ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ସଂଜାତମ୍ = ସମ୍ + ଜନ୍ + କ୍ତ ।

Text – 7

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

उक्तं च-

वदनं दशनैर्हीनं लाला स्रवति नित्यशः ।

न मतिः स्फुरति क्वापि वाले वृद्धे विशेषतः ॥ ४ ॥

ଉଲଂ ଚ –

ବଦନଂ ଦଶନୈହୀନଂ ଲାଳା ସୁବତି ନିତ୍ୟଶଃ ।

ନ ମତିଃ ସ୍ଫୁରତି କ୍ୱାପି ବାଳେ ବୃଦ୍ଧ ବିଶେଷତଃ ॥ ୪ ॥

ଅନ୍ୱୟ – (ବାଳବୃଦ୍ଧ) ବଦନଂ ଦଶନିଃ ହୀନଂ, ନିତ୍ୟଶଃ ଲାଳା ସୁବତି । କ୍ବାପି (ବିଷୟ) ବିଶେଷତଃ ବାଳେ ବୃଦ୍ଧ (ଚ) ମତିଃ ନ ସ୍ଫୁରତି ।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ବଦନମ୍ = ମୁଖ । ଦର୍ଶନଃ = ଦାନ୍ତଦ୍ବାରା । ନିତ୍ୟଶଃ = ସର୍ବଦା । ସୁବତି = ଝରିଥାଏ । ମତିଃ = ବୁଦ୍ଧି । ସ୍ଫୁରତି = ସ୍ଫୁରଣ ହୁଏ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – କୁହାଯାଇଛି – (ବାଳକ ଓ ବୃଦ୍ଧ ଉଭୟଙ୍କର ) ମୁଖ ଦନ୍ତହୀନ, ଉଭୟଙ୍କର ମୁଖରୁ ସର୍ବଦା ଲାଳ ଝରୁଥାଏ । କୌଣସି ବିଷୟରେ ମଧ୍ୟ ଏ ଦୁହିଁଙ୍କର ବିଶେଷତଃ ବାଳକଠାରେ ଓ ବୃଦ୍ଧଠାରେ ବୁଦ୍ଧି ସ୍ତୁରେ ନାହିଁ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ଦଶନୈହୀନମ୍ = ଦଶନିଃ + ହୀନମ୍ । କ୍ଵାପି = କୃ + ଅପି ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ବଦନଂ, ଲାଳା, ମଶଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ମ । ଦଶତିଃ = ହୀନ ଯୋଗେ ୩ୟା । ବାଳେ, ବୃଦ୍ଧି = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ମତିଃ = ମନ୍ + ସ୍କ୍ରିନ୍ ।

Text – 8

न वयं स्वर्गसमानो ……………… वनं यास्यामि।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ବୟଂ = ଆମ୍ଭେମାନେ । ନାନାବିଧାନ୍ = ଅନେକ ପ୍ରକାରର । ରାଜପୁତ୍ରୈ = ରାଜପୁତ୍ରଙ୍କଦ୍ବାରା । ପରିତ୍ୟଜ୍ୟ = ପରିତ୍ୟାଗ କରି । ଅଟବ୍ୟାମ୍ = ଅରଣ୍ୟରେ । କ୍ଷାରମ୍ = ଲବଣଯୁକ୍ତ । ତିକ୍ତମ୍ = ରାଗ । ରୂକ୍ଷ = କର୍କଶ ବା ଚିକ୍କଣ – ରହିତ । ଶ୍ରୁତ୍ଵା = ଶୁଣି । ପରିଣାମମ୍ = ଫଳାଫଳକୁ । କୁଳକ୍ଷୟମ୍ = ବଂଶନାଶ । ସ୍ଵୟମ୍ = ନିଜେ । ସାଂପ୍ରତମ = ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନ । ଯାସ୍ୟାମି = ଚାଲିଯିବି ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏଠାରେ ସ୍ବର୍ଗ ସମାନ ସୁଖଭୋଗକୁ, ରାଜପୁତ୍ରମାନଙ୍କ ସ୍ୱହସ୍ତରେ ପ୍ରଦତ୍ତ ବିବିଧ ଅମୃତତୁଲ୍ୟ ଭୋଜ୍ୟଦ୍ରବ୍ୟ ତ୍ୟାଗ କରି ଆମେମାନେ ବନ ମଧ୍ୟରେ କଷାୟ, କଟୁ, ତିକ୍ତ, କ୍ଷାର, ରୂକ୍ଷ ଫଳମାନ ଖାଇପାରିବୁ ନାହିଁ । ତାହା ଶୁଣି ଅଶ୍ରୁପ୍ଲାବିତ ଦୃଷ୍ଟିରେ ସେ ( ବାନର ଅଧୂପତି) କହିଲା – ଆରେ ରେ ମୂର୍ଖ ! ତୁମେମାନେ ଏ ସୁଖର ପରିଣାମ ଜାଣିନାହଁ ? ପାପକର୍ମର ରସାସ୍ଵାଦନ ସଦୃଶ ଏ ସୁଖର ପରିଣାମ ବିଷମୟ ହେବ । ତେଣୁ କୁଳର ବିନାଶ ମୁଁ ନିଜେ ଦେଖିପାରିବି ନାହିଁ, ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନ ବଣକୁ ଚାଲିଯାଉଛି ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ତମ୍ରାଟବ୍ୟାମ୍ = ତତ୍ର + ଅଟବ୍ୟାମ୍ । ତତ୍ତ୍ଵତ୍ୱାଶୁକଳୁଷାମ୍ = ତତ୍ + ଶୁକ୍ଳା + ଅଶୁକଳୁଷାମ୍ । ୟୂୟମେତସ୍ୟ ୟୂୟମ୍ + ଏତସ୍ୟ । ପାପର ସାସ୍ଵାଦନ ପ୍ରାୟମେତ ସୁଖମ୍ = ପାପର ସ + ଆସ୍ବାଦନ ପ୍ରାୟମ୍ + ଏତତ୍ + ସୁଖମ୍ । ବିଷବଦ୍ଭବିଷ୍ୟତି = ବିଷବତ୍ + ଭବିଷ୍ୟତି । ତଦହମ୍ = ତତ୍ + ଅହମ୍ । ନାବଲୋକୟିଷ୍ୟାମି = ନ + ଅବଲୋକୟିଷ୍ୟାମି ।

ସମାସ – ରାଜପୁ : = ରାଜ୍ଞ ପୁନଃ, ତୈ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ସ୍ଵହସ୍ତଦଭାନ୍ = ସ୍ୱସ୍ୟ ହସ୍ତୀ ( ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ), ତାଭ୍ୟ ଦତ୍ତମ୍, ତାନ୍ (୩ୟା ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ଅଶୁକଳୁଷାମ୍ = ଅଶ୍ରୁଭି କଳୁଷ, ତାମ୍ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । କୁଳକ୍ଷୟମ୍ = କୁଳସ୍ୟ କ୍ଷୟମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ବୟଂ, ସ୍ୱ, ସୂୟଂ, ଅହମ୍ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ରେ ରେ ମୂର୍ଖ =ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ସ୍ୱର୍ଗସମାଦୋପଭୋଗାନ୍, ନାନାବିଧାନ୍, ଭକ୍ଷବିଶେମାନ୍, ସ୍ଵହସ୍ତଦତ୍ତାନ୍, ଅମୃତକଳ୍ପାନ୍, ଫଳାନି, ଦୃଷ୍ଟି, ପରିଣାମଂ, କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଂ, ବନମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ରାଜପୁତ୍ରୈ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ଏତସ୍ୟ, ସୁଖସ୍ୟ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ଅଟବ୍ୟା, ପରିଣାମେ ଅଧ୍ଵରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଭୋଗ = ଭୁଞ୍ଜ୍ + ଘଣ୍ଟ୍ । ବିଶେଷ = ବି + ଶିଷ୍ + ଘଞ୍ଚେ । ପରିତ୍ୟଜ୍ୟ = ପରି + ତ୍ୟଜ୍ + ଲ୍ୟପ୍ । ଶ୍ରୁତ୍ଵା = ଶୁ + ସ୍କାଚ୍ । ଦୃଷ୍ଟିମ୍ = ଦୃଶ୍ + ଭିନ୍ । କୃତ୍ୱା = କୃ + କ୍ଲାବ୍।

Text – 9

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

उक्तं च- मित्रं व्यसनसंप्राप्तं स्वस्थानं परपीडितम्।

धन्यास्ते ये न पश्यन्ति देशभङ्ग कुलक्षयम् ॥ ५ ॥

ଉକ୍ତ ଚ – ମିତ୍ର ବ୍ୟସନସଂପ୍ରାପ୍ତ ସ୍ଵସ୍ଥାନଂ ପରପୀଡ଼ିତମ୍ ।

ଧନ୍ୟାସ୍ତେ ଯେ ନ ପଶ୍ୟନ୍ତି ଦେଶଭଙ୍ଗ କୁଳକ୍ଷୟମ୍ ॥ ୫ ॥

एवमभिधाय सर्वांस्तान् परित्यज्य स यूथाधिपोऽटव्यां गतः।

ଅନ୍ବୟ – ମିତ୍ର ବ୍ୟସନସଂପ୍ରାଫ୍ର ସ୍ଵସ୍ଥାନଂ ପରପୀଡ଼ିତଂ କୁଳକ୍ଷୟମ୍ – ଯେ ନ ପଶ୍ୟନ୍ତ ତେ ଧନ୍ୟା।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ମିତ୍ରମ୍ = ବନ୍ଧୁ । ବ୍ୟସନ = ଦୁଃଖ ବା ବିପଦ । ପର = ଅନ୍ୟ ବା ଶତ୍ରୁ । କୁଳକ୍ଷୟମ୍ = ବଂଶନଷ୍ଟ । ଯେ = ଯେଉଁମାନେ । ତେ = ସେମାନେ । ଏବମ୍ = ଏହିପରି । ଅଭିଧାୟ = କହି । ପୃଥାଧୂପ = ଦଳପତି ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ବନ୍ଧୁ ବିପଦରେ ପଡ଼ିବା, ନିଜର ସ୍ଥାନ ଅନ୍ୟଦ୍ଵାରା ଉପୀଡ଼ିତ ହେବା, ଦେଶଭଙ୍ଗ, କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ – ଏସବୁ ଯେଉଁମାନେ ଦେଖନ୍ତି ନାହିଁ, ସେମାନେ ଧନ୍ୟ । ଏହିପରି କହି ସେହି ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ପରିତ୍ୟାଗ କରି ସେ ଦଳପତି ଅରଣ୍ୟକୁ ଚାଲିଗଲା ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ଧନ୍ୟାସ୍ତେ = ଧନ୍ୟା + ତେ । ଏବମଭିଧାୟ = ଏବମ୍ + ଅଭିଧାୟ । ଯୂଥାଧୂପୋଽଟବ୍ୟାମ୍ = ପୃଥ + ଅଧୂପଃ + ଅଟବ୍ୟାମ୍ ।

ସମାସ – ସ୍ୱସ୍ଥାନମ୍ = ସ୍ଵସ୍ୟ ସ୍ଥାନମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ପରପୀଡ଼ିତମ୍ = ପରେଣ ପୀଡ଼ିତମ୍ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ଦେଶଭଙ୍ଗମ୍ = ଦେଶସ୍ୟ ଭଙ୍ଗମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । କୁଳକ୍ଷୟମ୍ = କୁଳସ୍ୟ କ୍ଷୟମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ଯୂଥାଧୂପଃ = ଯୂଥସ୍ୟ ଅଧୂପ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ଯେ, ତେ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ମିତ୍ର, ବ୍ୟସନସଂପ୍ରାପ୍ତ, ସ୍ଵସ୍ଥାନଂ, ପରପୀଡ଼ିତ୍ୟ, ଦେଶଭଙ୍ଗ, କୁଳକ୍ଷୟମ୍ : କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଅଟବ୍ୟାମ୍ = ଅଧୂକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ପ୍ରାପ୍ତମ୍ = ପ୍ର + ଆପ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଗତଃ = ଗମ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଅଭିଧାୟ = ଅଭି + ଧା + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ପରିତ୍ୟଜ୍ୟ = ପରି + ତ୍ୟଜ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ ।

Text – 10

अथ तस्मिन् गते ……………………………… जनसमूहमाकुलीचक्रुः।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଅଥ = ଏହାପରେ । ଅହନି = ଦିନରେ । ମେଷ = ମେଣ୍ଢା । ମହାନସେ = ରୋଷେଇଶାଳରେ । ସୂପକାରେଣ = ପାଚକଦ୍ବାରା । କିଂଚିତ୍ କିଛି । ସମାସାଦିତମ୍ = ପାଇବା । ତାଲ୍ୟମାନମ୍ = ବାଡ଼େଇ । ଅଶ୍ଵକୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ = ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାକୁ । ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟ = ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । କ୍ଷିତୌ = ଭୂମିରେ । ପ୍ରଭୁପତଃ = ଲୋଟିବାରୁ । ପଞ୍ଚତ୍ୱମ୍ = ମୃତ୍ୟୁକୁ । ତ୍ରୋଟୟିତ୍ୱ = ଫିଟାଇ ବା ଛିଡ଼ାଇ । ଇତଶ୍ଚେତଶ୍ଚ = ଏଣେତେଣେ । ତ୍ରେଷାୟମାଣା = ଘୋଡ଼ାଦ୍ଵାରା କରାଯାଉଥିବା ଶବ୍ଦ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏହାପରେ ସେ ଚାଲିଯା’ନ୍ତେ ଦିନେ ସେହି ମେଣ୍ଟାଟି ରନ୍ଧନଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । ପାଚକ ଅନ୍ୟ କିଛି ନପାଇ ଜଳନ୍ତା କାଷ୍ଠଖଣ୍ଡରେ ତାକୁ ପ୍ରହାର କରିବାରୁ ସେ ଜ୍ଵଳନ୍ତ ଶରୀରରେ ଚିତ୍କାର କରି କରି ନିକଟବର୍ତ୍ତୀ ଅଶ୍ୱଶାଳାରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କଲା । ସେଠାରେ ସେ ତୃଣପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଭୂମିରେ ଲୋଟିବାରୁ ସର୍ବତ୍ର ଏପରି ଅଗ୍ନିଶିଖା ଉଠିଲା ଯେ କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ଵ ଚକ୍ଷୁ ହରାଇ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ପଡ଼ିଲେ । କେତେକ ଅଶ୍ବ ବନ୍ଧନ ଛିନ୍ନକରି ଅର୍ଦ୍ଧଦଗ୍ଧ ଶରୀରରେ ବ୍ରେଷାରାବ କରି ଏଣେତେଣେ ଧାଇଁବାକୁ ଲାଗିଲେ । ଏହାଫଳରେ ଲୋକମାନେ ବ୍ୟାକୁଳ ହୋଇପଡ଼ିଲେ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ଗତେଽନ୍ୟ ସ୍ମିନ୍ନହନି = ଗତେ + ଅନ୍ୟସ୍ଥିନ୍ + ଅହନି । ନାନ୍ୟତ୍ = ନ + ଅନ୍ୟତ୍ । ତାବଦର୍ଧଜ୍ଜ୍ବଳିତକାଷ୍ଟେନ = ତାବତ୍ + ଅର୍ଧଜ୍ବଳିତକାଷ୍ଟେନ । ଶବ୍ଦାୟମାନୋଽଶ୍ଵକୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ = ଶବ୍ଦାୟମାନଃ + ଅଶ୍ଵକୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ । ପ୍ରତ୍ୟାସନ୍ନବର୍ଲିନ୍ୟାମ୍ = ପ୍ରତି + ଆସନ୍ନବର୍ଷିନ୍ୟାମ୍ । ସର୍ବତ୍ରାପି = ସର୍ବତ୍ର + ଅପି । ବହ୍ନିଜ୍ଵାଳାସ୍ତଥା = ବହ୍ନିଜ୍ୱାଳା + ତଥା । କେଚିଦଶଃ = କେଚିତ୍ + ଅଶ୍ୱ । ଇତଶ୍ଵେତଶ୍ଚ = ଇତଃ + ଚ + ଇତଃ + ଚ । ସର୍ବମପି = ସର୍ବମ୍ + ଅପି । ଜନସମୂହମାକୁଳୀଚତୁଃ = ଜନସମୂହମ୍ + ଆକୁଳୀଚତୁଃ ।

ସମାସ – ସୂପକାରେଣ = ସୂପିଂ କରୋତି ଇତି, ତେନ (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ଅଶ୍ଵକୁଟ୍ୟାମ୍ = ଅଶ୍ୱସ୍ୟ କୁଟୀ, ତସ୍ୟାମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ବହ୍ନିଜ୍ୱାଳା = ବହିଃ ଜ୍ଵାଳା (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ଜନସମୂହମ୍ = ଜନାନାଂ ସମୂହଃ, ତମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ସ୍ୱ, ମେଷ, ଅଶ୍ଳୀ, ସ୍ଫୁଟିତଲୋଚନା, ଅର୍ଦ୍ଧଦଗ୍ଧଶରୀରା, ଶ୍ଳେଷାୟମାଣା, ଧାବମାନଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ତାତ୍ସ୍ୟମାନଃ, ଜାଜ୍ୱଲ୍ୟମାନଶରୀରଃ = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧ ମା । ସୂପକାରେଣ, ଅର୍ଧଜ୍ବଳିତକାଷ୍ଟେନ = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । ପଞ୍ଚତ୍ୱ, ଜନସମୂହଂ, ବନ୍ଧନାନି = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ପ୍ରଭୁପତଃ = ଅପାଦାନେ ୫ମୀ । ତସ୍ୟ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ତସ୍ମିନ୍, ଗତେ = ଭାବେ ୭ମୀ । ଅନ୍ୟସ୍ମିନ୍, ଅହନି, ମହାନସେ, ଅଶ୍ବକୁଟିଂ, ଆସନ୍ନବର୍ଷିନ୍ୟା, ତୃଣପ୍ରାଚୁର୍ଯ୍ୟଯୁକ୍ତାୟାଂ, କ୍ଷିତୌ = ଅଧ୍ଵରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତି ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟ = ପ୍ର + ବିଶ୍ + କ୍ତ । ସମାସାଦିତମ୍ = ସମ୍ + ଆ + ସଦ୍ + ଣିଚ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଗତଃ = ଗମ୍ + କ୍ତ । ତ୍ରୋଟୟିତ୍ୱ = ତ୍ରୁଟ୍ + ଣିଚ୍ + କ୍ସାଚ୍ । ଧାବମାନଃ = ଧାବ୍ + ଶାନଚ୍ ।

Text – 11

अत्रान्तरे राजा ……………………………….. शालिहोत्रेण यत्-

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଅଶ୍ରାନ୍ତରେ = ଏହାପରେ । ସବିଷାଦଃ = ଦୁଃଖପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ । ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରଜ୍ଞାନ୍ = ଘୋଡ଼ାମାନଙ୍କର ଚିକିତ୍ସକମାନଙ୍କୁ । ଆହୂୟ = ଡାକି । ପ୍ରୋଚ୍ୟତାମ୍ = କୁହନ୍ତୁ । ଉପାୟ = କୌଶଳ । ତେ = ସେମାନେ । ଅପି = ମଧ୍ୟ । ବିଲୋକ୍ୟ = ଦେଖ୍ । ଅତ୍ର = ଏଠାରେ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏହି ଅବସରରେ ରାଜା ବିଷଣ୍ଣ ହୋଇ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରଶାସ୍ତ୍ରଜ୍ଞ ବୈଦ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କୁ ଡକାଇ କହିଲେ – ଆହେ ! ଏହି ଅଶ୍ଵମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ବ୍ୟଥାର ଉପଶମ ପାଇଁ କୌଣସି ଉପାୟ କୁହ । ସେମାନେ ମଧ୍ୟ ଶାସ୍ତ୍ରମାନ ଦେଖୁ କହିଲେ – ହେ ମହାରାଜ ! ଏ ବିଷୟରେ ଭଗବାନ୍ ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ର କହିଅଛନ୍ତି ଯେ –

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ଅତ୍ରାନ୍ତରେ = ଅତ୍ର + ଅନ୍ତରେ । ବୈଦ୍ୟାନାହ୍ୟ = ବୈଦ୍ୟାନ୍ + ଆହୂୟ । ପ୍ରୋଚ୍ୟତାମେଷାମଶ୍ଵାନାମ୍ = ପ୍ରୋଚ୍ୟତାମ୍ + ଏଷାମ୍ + ଅଶ୍ବିନାମ୍ । କଣ୍ଟିଦ୍ଦାହୋପଶ୍ଚିମନୋପାୟଃ = କଶ୍ଚିତ୍ + ଦାହ + ଉପଶମନ + ଉପାୟ । ତେଽପି = ତେ + ଅପି । ପ୍ରୋକ୍ତମତ୍ର = ପ୍ରୋକ୍ତମ୍ + ଅତ୍ର ।

ସମାସ – ସବିଷାଦଃ = ବିଷାଦେନ ସହ ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନଃ (ସହାର୍ଥ ବହୁବ୍ରୀହିଃ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ରାଜା, ତେ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ଭୋ !, ଦେବ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରଜ୍ଞାନ୍, ବୈଦ୍ୟାନ୍, ଶାସ୍ତ୍ରାଣି = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଭଗବତା, ଶାଳିହୋତ୍ରେଣ = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । ଏଷାମ୍, ଅଶ୍ଵାନାମ୍ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ବିଷୟ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ବିଷାଦ = ବି + ଷଦ୍ + ଘଞ୍ଜ୍ । ବିଲୋକ୍ୟ = ବି + ଲୋକ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ପ୍ରୋକ୍ତମ୍ = ପ୍ର + ବଚ୍ + କ୍ତ ।

Text – 12

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

कपीनां मेदसा दोषो वह्निदाहसमुद्भवः।

अश्वानां नाशमभ्येति तमः सूर्य्योदये यथा ॥ ६ ॥

କପୀନାଂ ମେଦସା ଦୋଷେ ବହ୍ନିଦାହସମୁଦ୍ଭବାଃ ।

ଅଶ୍ଵାନାଂ ନାଶମସ୍ତେତି ତମଃ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟେ ଯଥା || ୬ ||

ଅନ୍ବୟ – ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟେ ଯଥା ତମ ନାଶମ୍ ଅଭ୍ୟତି, (ତଥା) କପୀନାଂ ମେଦସା ଅଶ୍ଵାନାଂ ବହ୍ନିଦାହସମୁଦ୍ଭବାଃ ଦୋଷ ନାଶମ୍ ଅଜ୍ୟୋତି ।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଯଥା = ଯେପରି । ତମଃ = ଅନ୍ଧକାର । ନାଶମ୍ = ନଷ୍ଟ । ଅଭ୍ୟତି = ହୋଇଥାଏ । କପୀନାମ୍ = ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ମାନଙ୍କର । ମେଦସା = ମେଦଦ୍ୱାରା ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ହେଲେ ଅନ୍ଧକାର ଯେପରି ଦୂର ହୋଇଥାଏ, ବାନରମାନଙ୍କର ମେଦଦ୍ଵାରା ଅଶୁମାନଙ୍କର ଦାହଜନିତ ରୋଗ ସେହିପରି ବିନଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇଥାଏ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ନାଶମଜ୍ୟୋତି = ନାଶମ୍ + ଅଭ୍ୟତି ।

ସମାସ – ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟେ = ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟସ୍ୟ ଉଦୟଃ, ତସ୍ମିନ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁରଃ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ବହ୍ନିଦାହସମୁଦ୍ଭବାଃ, ଦୋଷୀ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ମେଦସା = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ଅଶ୍ୱିନାଂ, କପୀନାମ୍ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟେ = ଅଧୀକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଦୋଷୀ = ଦୁଷ୍ + ଘଞ୍ଚ।

Text – 13

तत्क्रियताम् ……………………………….. व्यापादिता इति।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଦ୍ରାଗ୍ = ଶୀଘ୍ର । ଆକର୍ୟ୍ଯ = ଶୁଣି । ଆଦିଷ୍ଟବାନ୍ = ଆଦେଶ ଦେଲେ । ଲଗୁଡ଼ = ବାଡ଼ି । ପାଷାଣ = ପଥର । ବ୍ୟାପାଦିତା = ମରିଗଲେ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ତେଣୁ ଅତିଶୀଘ୍ର ଏହି ଚିକିତ୍ସା କରାଯାଉ, ଯେପରିକି ଅଶୁମାନେ ଅଗ୍ନିଦାହ ଯୋଗୁଁ ମୃତ୍ୟୁମୁଖରେ ନ ପଡ଼ନ୍ତି । ସେ ମଧ୍ୟ ତାହା ଶୁଣି ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରମାନଙ୍କୁ ମାରିବାପାଇଁ ଆଦେଶ ଦେଲେ । ଅଧୂକ କହିବା ନିଷ୍ପ୍ରୟୋଜନ । ସେ ସମସ୍ତ ବାନରମାନେ ମଧ୍ୟ ବିଭିନ୍ନ ଅସ୍ତ୍ର, ବାଡ଼ି, ପଥରାଦିଦ୍ୱାରା ନିହତ ହେଲେ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ତକ୍ରିୟତାମେତଚିକିତ୍ସିତମ୍ = ତତ୍ + କ୍ରିୟତାମ୍ + ଏତତ୍ + ଚିକିତ୍ସିତମ୍ । ଯାବନୈତେ = ଯାବତ୍ + ନ + ଏତେ । ସୋଽପି = ଡଃ + ଅପି । ତଦାକର୍ୟ୍ଯ ତତ୍ + ଆକର୍ୟ୍ୟ । ସର୍ବେଽପି = ସର୍ବେ + ଅପି । ବିବିଧାୟୁଧଲଗୁଡ଼ପାଷାଣାଦିଭିବ୍ୟାପାଦିତା = ବିବଧ + ଆୟୁଧଲଗୁଡ଼ପାଷାଣ + ଆଦିଭଃ + ବ୍ୟାପାଦିତା ।

ସମାସ – ଦାହଦୋଷେଣ = ଦାହଜନିତ ଦୋଷୀ, ତେନ (ମଧ୍ୟପଦଲୋପୀ କର୍ମଧାରୟ) । ବାନରବଧମ୍ = ବାନରାମାଂ ବଧମ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ଏତେ, ବାନରାଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ସ୍ୱ, ସର୍ବେ = ଅପି ଅବ୍ୟୟ ଯୋଗେ ୧ମା । ବଧମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଦାହଦୋଷଣ, ବିବିଧାୟୁଧଲଗୁଡ଼ପାଷାଣାଦିଭି, ଅଟବ୍ୟାମ୍ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଆକର୍ୟ୍ଯ = ଆ + କଣ୍ଠ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ଆଦିଷ୍ଟବାନ୍ = ଆ + ଦିଶ୍ + କ୍ତବତୁ । ବ୍ୟାପାଦିତଃ = ବି + ଆ + ପଦ୍ + ଣିଚ୍ + କ୍ତ ।

Text – 14

अथ सोऽपि ………………………………. करिष्यामि? उक्तंच-

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଅଥ = ଏହାପରେ । ଅପି = ମଧ୍ୟ । ସୁତ = ପୁତ୍ର । ସଂକ୍ଷୟମ୍ = ମୃତ୍ୟୁ । ବିଷାଦମ୍ = ଦୁଃଖକୁ । ବନାଦ୍ : ବଣରୁ । ପର୍ଯ୍ୟଟତି = ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିଛି । ଅପସଦସ୍ୟ = ଅଧମର । ଅପକୃତ୍ୟମ୍ = ଅନିଷ୍ଟକୁ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏହାପରେ ସେ ବାନରଦଳପତି ମଧ୍ୟ ସେହି ପୁଅ, ନାତି, ଭାଇର ପୁଅ, ଭଉଣୀ ପୁଅ ଆଦିଙ୍କର ନିଧନକୁ ଜାଣି ଅତ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଦୁଃଖୁତ ହେଲା । ସେ ଆହାର ତ୍ୟାଗକରି ବଣରୁ ବଣକୁ ବୁଲିଛି ଓ ଚିନ୍ତା କରିଛି, କିପରି ମୁଁ ସେହି ଅଧମ ରାଜାର ପ୍ରତିଶୋଧ ନେଇ ତା’ର ଅନିଷ୍ଟ ସାଧନ କରିବି ? କୁହାଯାଇଛି –

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ସୋଽପି = ନଃ + ଅପି । ବାନରଯୂଥପସ୍ତମ୍ଭ = ବାନରଯୂଥପଃ + ତମ୍ । ବିଷାଦମୁପାଗତଃ = ବିଷାଦମ୍ + ଉପାଗତଃ । ତ୍ୟକ୍ତାହାରକ୍ରିୟ = ତ୍ୟକ୍ତ + ଆହାରକ୍ରିୟା । ବନାଦ୍ନମ୍ = ବନାତ୍ + ବନମ୍ । ଅଚିନ୍ତୟଜ = ଅଚିନ୍ତୟତ୍ + ଚ । କଥମହମ୍ = କଥମ୍ + ଅହମ୍ । ନୃପାପସଦସ୍ୟାମୃଣତାକୃତ୍ୟେନାପକୃତ୍ୟମ୍ ନୃପ + ଅପସଦସ୍ୟ + ଅନ୍ଧଣତା + ଅକୃତ୍ୟେନ + ଅପକ୍ବତ୍ୟମ୍ ।

ସର୍ମାସ – ବାନରଯୂଥପଃ = ବାନରାଣା ପୃଥୀ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ), ତଂ ପାତି ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ତ୍ୟକ୍ତାହାରକ୍ରିୟଃ = ତ୍ୟକ୍ତା ଆହାରକ୍ରିୟା ଯେନ ଡଃ (ବହୁବ୍ରୀହିଃ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ବାନରଯୂଥପଃ, ସ୍ୱ, ତ୍ୟକ୍ତଆହାରକ୍ରିୟା, ଅହମ୍ = କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ତଂ, ସଂକ୍ଷୟଂ, ବିଷାଦଂ, ବନଂ, ଅପକୃତ୍ୟମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ବନାତ୍ = ଅପାଦାନେ ୫ମୀ । ତସ୍ୟ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଜ୍ଞାତ୍ମା = ଜ୍ଞା + ସ୍କାଚ୍ । ତ୍ୟକ୍ତା = ତ୍ୟଜ୍ + କ୍ତ ।

Text – 15

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

मर्षयेद्धर्षणां योऽत्र वंशजां परनिर्मिताम्।

भयद्वा यदि वा कामात् स ज्ञेयः पुरुषाधमः ॥ ७ ॥

ମର୍ଷୟେଦ୍ଧର୍ଷଣଂ ଯୋଽତ୍ରବଂଶଂ ପରନିର୍ମିତାମ୍ ।

ଭୟଦ୍ ଯଦି ବା କାମାତ୍ ସ ଜ୍ଞେୟଃ ପୁରୁଷାଧମଃ ॥ ୭॥

ଅନ୍ୱୟ – ଅତ୍ର ଯଃ ଭୟାତ୍ ବା କାମାତ୍ ବା ଯଦି ବଂଶଜା ପରନିର୍ମିତାଂ ଧର୍ଷଣା ମର୍ଷୟେତ୍ ଡଃ ପୁରୁଷାଧମଃ ଜ୍ଞେୟଃ । ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଅତ୍ର = ଏଠାରେ (ସଂସାରରେ) । ଭୟାତ୍ = ଭୟ ହେତୁରୁ । କାମାତ୍ = କାମ ହେତୁରୁ । ବଂଶଜାମ୍ = ନିଜର ବଂଶଜମାନଙ୍କର । ପର = ଶତ୍ରୁ । ଧର୍ଷଣାମ୍ = ଅତ୍ୟାଚାରକୁ । ମର୍ଷୟେତ୍ = ସହିଯାଇପାରେ । ଜ୍ଞେୟଃ = ବୋଲାଏ ବା ଜଣାପଡ଼େ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏ ସଂସାରରେ ଯେଉଁ ଲୋକ ଭୟ ହେତୁରୁ ଅଥବା ଲୋଭ ହେତୁରୁ ନିଜ ନିଜ କୁଳ ପ୍ରତି ଶତ୍ରୁର ଅତ୍ୟାଚାରକୁ ସହିଯାଏ, ସେ ପୁରୁଷମାନଙ୍କ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ନିତାନ୍ତ ଅଧମରୂପେ ପରିଗଣିତ ହୁଏ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ମର୍ଷୟେଦ୍ଧର୍ଷଣାମ୍ = ମର୍ଷୟେତ୍ + ଧର୍ଷଣାମ୍ । ଯୋଽତ୍ର = ଯଃ + ଅତ୍ର । ଭୟାଦ୍ବା = ଭୟାତ୍ + ବା । ପୁରୁଷାଧମଃ = ପୁରୁଷ + ଅଧମଃ ।

ସମାସ – ପରନିର୍ମିତାମ୍ = ପରଃ ନିର୍ମିତଃ, ତେଷାମ୍ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ଯଃ, ସ୍ୱ, ପୁରୁଷାଧମଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ଭୟାତ୍, କାମାତ୍ = ହେତୌ ୫ମୀ । ଧର୍ଷଣା, ବଂଶଜଂ, ପରନିର୍ମିତାମ୍ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଜ୍ଞେୟଃ = ଜ୍ଞା + ଯତ୍ !

Text – 16

अथ तेन वृद्धवानरेण ……………………… तत् कर्त्तव्यमिति।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ପିପାସା = ତୃଷା । ସରଃ = ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ । ପଦପଂକ୍ତି = ପାଦଚିହ୍ନ । ନିଷ୍କ୍ରମଣମ୍ = ଲେଉଟିବା ବା ଫେରିବା । ନୂନମ୍ = ନିଶ୍ଚୟ । ପଦ୍ମିନୀନାଳମ୍ = ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ । ନିଷ୍କ୍ରମ = ବାହାରି । ସଲିଳେ = ଜଳରେ । ମେ = ମୋର । ଧୂନଃ = ଶଠ । ତୁଷ୍ଟ = ସନ୍ତୁଷ୍ଟ । ବାଞ୍ଛମ୍ = ଇଚ୍ଛିତ । କପି = ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ । ବାହ୍ୟତଃ = ବାହାରୁ । ଆହ = କହିଲା । ବୈରମ୍ = ଶତ୍ରୁତା । ଭୂପତିମ୍ = ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ । ବାକ୍ସପ୍ରପଞ୍ଚେନ = କଥା ଛଳରେ । ଶ୍ରୁତ୍ୱା = ଶୁଣି । ଦତ୍ତା = ଦେଇ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏହାପରେ ସେହି ବାନର ତୃଷାତୁର ହୋଇ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରୁ କରୁ କମଳ ପରିପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ଏକ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ନିକଟରେ ପହଞ୍ଚିଲା । ସେ ସୂକ୍ଷ୍ମଭାବରେ ନିରୀକ୍ଷଣ କରି ଦେଖୁଲା ଯେ ବନବାସୀ ମନୁଷ୍ୟମାନଙ୍କର ସରୋବରରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବାର ପାଦଚିହ୍ନ ରହିଛି; କିନ୍ତୁ ଫେରିଆସିବାର ପାଦଚିହ୍ନ ନାହିଁ । ତେଣୁ ସେ ଚିନ୍ତାକଲା ଯେ ନିଶ୍ଚୟ ଏଠାରେ ଜଳ ମଧ୍ଯରେ ଏକ ଦୁଷ୍ଟଗ୍ରାହ ରହିଅଛି । ତେଣୁ ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ଧରି ଦୂରରୁ ରହି ଜଳପାନ କରିବି । ସେହିପରି କରନ୍ତେ ସେ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ଏକ ରାକ୍ଷସ ବାହାରି କଣ୍ଠରେ ରନ୍ଧମାଳା ଧାରଣ କରି ତାକୁ କହିଲା – ଆହେ ଏଠାରେ ଯେ ପାଣି ମଧ୍ୟରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରେ ସେ ମୋର ଭକ୍ଷଣୀୟ ହୋଇଥାଏ । କିନ୍ତୁ ଏପରି କୌଶଳୀ ଚତୁର ଲୋକ ନାହିଁ, ଯେକି ତୁମ ଭଳି ଏ ଉପାୟରେ ଜଳପାନ କରିବ, ତେଣୁ ମୁଁ ସନ୍ତୁଷ୍ଟ । ମନର ଇଚ୍ଛାନୁସାରେ ବର ପ୍ରାର୍ଥନା କର । ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ କହିଲା – ଆହେ ! ତୁମର ଭୋଜନ କରିବାର ଶକ୍ତି କେତେ ? ସେ କହିଲା ଜଳରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରୁଥିବା ଶତ, ସହସ୍ର, ଅୟୁତ, ଲକ୍ଷ ପ୍ରାଣୀଙ୍କୁ ମଧ୍ୟ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କରିପାରେ, ବାହାରୁ ଶୃଗାଳ ମଧ୍ୟ ମୋତେ ଅପମାନିତ କରିଥାଏ । ବାନର କହିଲା, ଜଣେ ରାଜା ସହିତ ମୋର ଘୋର ଶତ୍ରୁତା ରହିଛି । ଯଦି ଏହି ରମାଳାଟିକୁ ମୋତେ ପ୍ରଦାନ କରିବ ତେବେ ସପରିବାର ମଧ୍ୟ ସେହି ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ କଥାଛଳରେ ଲୋଭ ଦେଖାଇ ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ଯେପରି ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବେ ସେହିପରି କରିବି । ସେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ମଧ୍ୟ ତା’ର ଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧାପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ବଚନ ଶୁଣି ରନ୍ଥମାଳାଟି ଦେଇ କହିଲା – ହେ ମିତ୍ର ! ଯାହା ଉଚିତ ମନେକରୁଛ, ତାହା କରିବା ଉଚିତ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ପିପାସାକୁଳେନ = ପିପାସା + ଆକୁଳେନ । ତଦ୍ବସୂକ୍ଷେକ୍ଷିକୟାବଲୋକୟତି = ତତ୍ + ଯାବତ୍ + ସୂକ୍ଷ୍ମ + ଇକ୍ଷିକୟା + ଅବଲୋକୟତି । ତାବଦ୍ବନଚର = ତାବତ୍ + ବନଚର । ପଦପଂକ୍ତିପ୍ରବେଶୋଽସ୍ତି = ପଦପଂକ୍ତିପ୍ରବେଶଃ + ଅସ୍ତି । ତତଶ୍ଚିନ୍ତିତମ୍ = ତତଃ + ଚିନ୍ତିତମ୍ । ନୂନମତ୍ର = ନୂନମ୍ + ଅତ୍ର । ପଦ୍ମିନୀନାଳମାଦାୟ = ପଦ୍ମିନୀନାଳମ୍ + ଆଦାୟ । ଦୂରସ୍ପୋଽପି ଦୂରହଃ + ଅପି । ତଥାନୁଷ୍ଠିତେ = ତଥା + ଅନୁଷ୍ଠିତେ । ତନ୍ମଧ୍ୟାଦ୍ରାକ୍ଷକଃ = ତତ୍ + ମଧ୍ୟାତ୍ + ରାକ୍ଷମଃ । ରମାଳାବିଭୂଷିତକଣ୍ଠସ୍ତମୁବାଚ = ରତ୍ନମାଳାବିଭୂଷିତକଣ୍ଠ + ତମ୍ + ଉବାଚ । ତନ୍ନାସ୍ତି = ତତ୍ + ନ + ଅସ୍ଥି । ଧୂର୍ରତରତ୍ୱମୋଽନ୍ୟା = ଧୂରତରଃ + ତ୍ଵତ୍ଵସମଃ + ଅନ୍ୟ । ଯତ୍ପାନୀୟମନେନ = ଯତ୍ + ପାନୀୟମ୍ + ଅନେନ । ତତସ୍ତୁଷ୍ଟୋଽହମ୍ = ତତଃ + ତୁଷ୍ଟ + ଅହମ୍ । କପିରାହ = କପି + ଆହ । ଶୃଗାଳୋଽପି = ଶୃଗାଳ + ଅପି । ସହାତ୍ୟନ୍ତମ୍ = ସହ + ଅତ୍ୟନ୍ତମ୍ଭ । ଯଦ୍ୟନାମ୍ = ଯଦି + ଏନାମ୍ । ସୋଽପି = ପଃ + ଅପି । ବଚସ୍ତସ୍ୟ = ବତଃ + ତଥ୍ୟ । କର୍ତ୍ତବ୍ୟମିତି କର୍ତ୍ତବ୍ୟମ୍ + ଇତି ।

ସମାସ – ବୃଦ୍ଧିବାନରେଣ = ବୃଦ୍ଧ ବାନରଃ, ତେନ (କର୍ମଧାରୟ) । ପିପାସାକୁଳେନ = ପିପାସୟା ଆକୁଳ, ତେନ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ବନଚର = ବନେ ଚରତି ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ଜଳାନ୍ତେ = ଜଳସ୍ୟ ଅନ୍ତଃ, ତସ୍ମିନ୍ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତପୁରୁଷ ) । ଦୂରସ୍ଥ = ଦୂରେ ତିଷ୍ଠତି ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ପୁରୁରଃ) । ଭୂପତିନା = ଭୂନଃ ପତିଃ, ତେନ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ରନ୍ଧମାଳାମ୍ = ରନ୍ସ୍ୟ ମାଳା, ତାମ୍ ( ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ସପରିବାରମ୍ = ପରିବାରେଣ ସହ ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନମ୍ (ସହାର୍ଥ ବହୁବ୍ରୀହିଃ) । ବାକ୍ସପ୍ରପଞ୍ଚେନ = ବାସ୍ୟା ପ୍ରପଞ୍ଚମ୍, ତେନ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ପଦପଂକ୍ତିପ୍ରବେଶଃ, ରାକ୍ଷସ୍ୱ, ଯଃ, ସ୍ୱ, ଅହଂ, କପି, ଭକ୍ଷଣଶନ୍ତଃ, ବାନରଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ଭୋ !, ଭୋ ମିତ୍ର ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ପଦ୍ମିନୀଖଣ୍ଡମଣ୍ଡିତଃ, ସରଃ = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧ ମା । ଦୂରସ୍ଥ, ଶୃଗାଳୀ, ସ = ଅପି ଅବ୍ୟୟ ଯୋଗେ ୧ମା । ପଦ୍ମିନୀ ନାନଂ, ଜଳଂ, ପ୍ରବେଶଂ, ମାଂ, ଏକାଂ, ରନୁମାଳା, ତଂ, ଭୂପତଂ, ଶ୍ରଦ୍ଧେୟଂ, ବତଃ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ତେନ, ବୃଦ୍ଧବାନରେଣ = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । ପିପାସାକୁଳେନ, ଭ୍ରମତା, ଦୁଷ୍ଟଗ୍ରାହେଣ, ଅନେନ, ବିଧ, ବାକ୍ସପ୍ରପଞ୍ଚେନ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ଭୂପତିନା = ସହ ଯୋଗେ ୩ୟା । ମେ = ସଂପ୍ରଦାନେ ୪ର୍ଥୀ । ତନ୍ମଧ୍ୟାତ୍ = ଅପାଦାନେ ୫ମୀ । ମନୁଷ୍ୟାମାଂ, ତେ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ଅନୁଷ୍ଠିତେ = ଭାବେ ସପ୍ତମୀ । ଜଳାନ୍ତେ, ସଲିଳେ, ସରସି = ଅଧୂକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ସମାସାଦିତମ୍ = ସମ୍ + ଆ + ସଦ୍ + ଣିଚ୍ + କ୍ତ । ନିଷ୍କ୍ରମ୍ୟ = ନିଃ + କ୍ରମ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ପାନୀୟମ୍ = ପା + ଆନୀୟର୍ । ତୁଷ୍ଟୀ = ତ୍ରୁଷ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଶକ୍ତି = ଶକ୍ + ଭିନ୍ । ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟ = ପ୍ର + ବିଶ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଲୋଭୟିତ୍ୱ = ଲୁଭ୍ + ଣିଚ୍ + କ୍ଵାଚ୍ । ଶୁଦ୍ଧା = ଶୁ + କ୍ଵାଚ୍ । ଦତ୍ତା = ଦା + ଷ୍ଟ୍ରାଚ୍ ! କର୍ତ୍ତବ୍ୟମ୍ = କୃ + ତଥ୍ୟ।

Text – 17

वानरोऽपि …………………………….. निःसरति।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଜନଃ = ଲୋକମାନଙ୍କଦ୍ବାରା । ଯୂଥପ ! = ହେ ଦଳପତି ! କୁତ୍ର = କେଉଁଠାରେ । ଲଜ୍ଜା = ପାଇଲେ । ତିରସ୍କରୋତି = ନିନ୍ଦା କରିଥାଏ । ଗୁପ୍ତତରମ୍ = ଗୋପନୀୟ । ମହରଃ = ବଡ଼ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ । ଧନଦଃ = କୁବେର । ନିମଜ୍ଜତି = ବୁଡ଼େ ବା ଡୁବେ । ନିଃସରତି = ବାହାରେ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ବାନର ମଧ୍ଯ ରହାରରେ ନିଜର କଣ୍ଠଦେଶକୁ ସୁଶୋଭିତ କରି ବୃକ୍ଷ ଓ ରାଜପ୍ରାସାଦମାନଙ୍କ ଉପରେ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିବାରୁ ଲୋକେ ତାହାକୁ ଦେଖୁ ପଚାରିଲେ, ହେ ବାନରଯୂଥପତି ! ତୁମେ ଏତେ କାଳ ହେଲା କେଉଁଠି ଥିଲ ? ଏଡ଼େ ସୁନ୍ଦର ରନ୍ଥମାଳା କେଉଁଠୁ ପାଇଲ ? ଏହାର ତେଜ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟକିରଣକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ତିରସ୍କାର କରୁଛି । ବାନର କହିଲା – ଗୋଟିଏ ଅରଣ୍ୟ ମଧ୍ୟରେ କୁବେରଦ୍ଵାରା ନିର୍ମିତ ଏକ ଅତି ଗୁପ୍ତ ସରୋବର ଅଛି । ରବିବାର ଦିନ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ସମୟରେ ଯଦି କେହି ଉକ୍ତ ସରୋବରରେ ବୁଡ଼ ପକାଏ ତେବେ ସେ କୁବେରଙ୍କ ପ୍ରସାଦରୁ ଏହିପରି ରନ୍ମାଳାରେ କଣ୍ଠକୁ ସୁଶୋଭିତ କରି ଜଳରୁ ବାହାରି ଆସେ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ବାନରୋଽପି = ବାନରଃ + ଅପି । ଜନୈର୍ଦ୍ଧିଷ୍ଟ = ଜନିଃ + ଦୃଷ୍ଟୀ । ପୃଷ୍ଟଣ୍ଟ = ପୃଷ୍ଟୀ + ଚ। ଭବାନିୟନ୍ତମ୍ = ଭବାନ୍ + ଇୟନ୍ତମ୍ । ଭବତେଦୂଗ୍ରନ୍ଥମାଳା = ଭବତା + ଇଦୃକ୍ + ରମାଳା । ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟମପି = ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟମ୍ + ଅପି । କୁତ୍ରଚିଦରଣ୍ୟ = କୁତ୍ରଚିତ୍ + ଅରଣ୍ୟ । କଣ୍ଟିନିମମ୍ମତି = କଶ୍ଚିତ୍ + ନିମଜ୍ଜତି ।

ସମାସ – ବୃକ୍ଷପ୍ରାସାଦେଷୁ = ବୃକ୍ଷ ଚ ପ୍ରାସାଦଃ ଚ, ତେଷୁ (ଦ୍ବନ୍ଦ୍ବ) । ମହସରଃ = ମହାନ୍ ସରଃ ( କର୍ମଧାରୟ) । ଧନଦନିର୍ମିତମ୍ = ଧନଂ ଦଦାତି ଇତି, ଧନଦଃ (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ), ତେନ ନିର୍ମିତମ୍ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ରବିବାସରେ = ରବି ନାମ ବାସରଃ, ତସ୍ମିନ୍ (ମଧ୍ୟପଦଲୋପୀ କର୍ମଧାରୟ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ରମାଳାବିଭୂଷିତକଣ୍ଠ, ଭବାନ୍, ଯା, ବାନରଃ, ମହତ୍ଵରଃ, ଯଃ, କଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ମା । ଭୋ ଯୂଥପ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ବାନରଃ = ଅପି ଅବ୍ୟୟ ଯୋଗେ ୧ମା । ରନ୍ମାଳା = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧୩ । ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟ, ଗୁପ୍ତତରମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଜନୈ, ଭବତା = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । ବୃକ୍ଷପ୍ରାସାଦେଷୁ, ଦୀପ୍ତି, ଅରଣ୍ୟ, ରବିବାସରେ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ । ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟ, ଅର୍ବୋଦିତେ = ଭାବେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଭ୍ରମନ୍ = ଭ୍ରମ୍ + ଶତୃ । ଦୃଷ୍ଟି = ଦୃଶ୍ + କ୍ତ । ପୃଷ୍ଠ = ପ୍ରଚ୍ଛ + କ୍ତ । ସ୍ଥିତଃ = ସ୍ଥା + କ୍ତ । ଲଜ୍ଜା = ଲଭ୍ + ୬ + ଟାପ୍ । ନିର୍ମିତମ୍ = ନିର୍ + ମା + ଲୁ ।

Text – 18

अथ भूभुजा तदाकर्ण्य …………………………………. साध्विदमुच्यते-

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଭୂଭୁଜା = ରାଜା । ତଦାକର୍ଯ୍ୟ = ତାହା ଶୁଣି । ସମାହୂତଃ = ଡକାହେଲା । ସରଃ = ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ । କହିଃ = ମାଙ୍କଡ଼ । ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟଃ = ବିଶ୍ୱାସ । ପ୍ରେଷୟ = ପଠାଅ । ତଚ୍ଛତ୍ମା = ତାହା ଶୁଣି । ନୃପତିଃ = ରାଜା । ଆହ = କହିଲେ । ସପରିଜନଃ = ପରିବାର ସହିତ । ଏଷ୍ୟାମି = ଆସିବି । ପ୍ରଭୃତା = ପ୍ରଚୁର । ତଥାନୁଷ୍ଠିତେ = ସେପରି କରନ୍ତେ । କଳତ୍ର = ପନ୍ଥୀ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏହାପରେ ରାଜା ଏହା ଶୁଣିପାରି ସେହି ବାନରକୁ ଡାକି ପଚାରିଲେ, ହେ ଯୂଥାଧୂପ ! ଏ କଥା କ’ଣ ସତ୍ୟ ? ରନ୍ମାଳାରେ ପରିପୂର୍ଣ୍ଣ ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ କେଉଁଠାରେ ଅଛି ? ବାନର କହିଲା, ହେ ପ୍ରଭୁ ! ପ୍ରତ୍ୟକ୍ଷରେ ମୋ ଗଳାରେ ପଡ଼ିଥିବା ଏହି ରନ୍ଥମାଳା ଦେଖୁ ଆପଣଙ୍କର ବିଶ୍ଵାସ ହେବ । ତେଣୁ ଯଦି ଆପଣଙ୍କର ରନ୍ଧମାଳାର ପ୍ରୟୋଜନ ଥାଏ, ତାହାହେଲେ କାହାକୁ ମୋ ସଙ୍ଗେ ପଠାନ୍ତୁ ଯେ ଦେଖାଇଦେବି । ଏହା ଶୁଣି ରାଜା କହିଲେ, ସେପରି ହେଲେ ମୁଁ ନିଜେ ମୋର ସମସ୍ତ ପରିବାର ସହିତ ଯିବି ଯଦ୍ବାରା ଅନେକ ରନ୍ଥମାଳା ପାଇପାରିବୁ । ବାନର କହିଲା, ହେ ପ୍ରଭୁ ! ଏହିପରି କରନ୍ତୁ । ସେହିପରି କରାଯା’ନ୍ତେ ରନ୍ଗମାଳା ପାଇବା ଲୋଭରେ ରାଜାଙ୍କ ସହିତ ସମସ୍ତ ପନ୍ଥୀ ଓ ଭୃତ୍ୟ ପ୍ରଭୃତି ଚାଲିଲେ । ବାନର ମଧ୍ଯ ରାଜାଙ୍କଦ୍ୱାରା କ୍ରୋଡ଼ରେ ବସାଇ ଅତି ସୁଖରେ ପ୍ରୀତିପୂର୍ବକ ନିଆଗଲା । ଅଥବା ଯଥାର୍ଥରେ କୁହାଯାଇଛି –

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ତଦାକର୍ୟ୍ଯ = ତତ୍ + ଆକର୍ୟ୍ୟ । ପୃଷ୍ଟଶ୍ଚ = ପୃଷ୍ଟୀ + ଚ । ଯୂଥାଧୂପ = ଯୂଥ + ଅଧୂପ । ସତ୍ୟମେତତ୍ = ସତ୍ୟମ୍ + ଏତତ୍ । ସରୋଽ = ସରଃ + ଅସ୍ଥି । କ୍ଵାପି = କୃ + ଅପି । କପିରାହ = କହିଃ + ଆହ । ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟସ୍ତେ ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟଃ + ତେ । ତଦ୍ୟଦି = ତତ୍ + ଯଦି । ତନ୍ମୟା = ତତ୍ + ମୟା । କମପି = କମ୍ + ଅପି । ତଛୁଡା଼ = ତତ୍ + ଶୁଦ୍ଧା । ନୃପତିରାହ = ନୃପତିଃ + ଆହ । ଯଦେବମ୍ = ଯଦି + ଏବମ୍ । ତଦହମ୍ = ତତ୍ + ଅହମ୍ । ସ୍ବୟମେଷ୍ୟାମି = ସ୍ବୟମ୍ + ଏଷ୍ୟାମି । ତଥାନୁଷ୍ଠିତେ = ତଥା + ଅନୁଷ୍ଠିତେ । ବାନରୋଽପି = ବାନରଃ + ଅପି । ସ୍ମୋସଙ୍ଗ = ସ୍କୃ + ଉତ୍ସଙ୍ଗ । ପ୍ରୀତିପୂର୍ବମାନୀୟତେ = ପ୍ରୀତିପୂର୍ବମ୍ + ଆନୀୟତେ । ସାଧିଦମୁଚ୍ୟତେ = ସାଧୁ + ଇଦମ୍ + ଉଚ୍ୟତେ ।

ସମାସ – ଭୂଭୁଜା = ଭୁବଂ ଭୁଜନ୍ତି ଇତି, ତେନ (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ଯୂଥାଧୂପ = ପୃଥକ୍ୟ ଅଧ୍ଯ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ମତ୍କଣ୍ଠସ୍ଥିତୟା = ମମ କଣ୍ଠୀ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ), ତସ୍ମିନ୍ ସ୍ଥିତଃ, ତୟା (ସପ୍ତମୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ନୃପତିଃ = ନୃଣା ପତିଃ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ସପରିଜନଃ = ପରିଜନେନ ସହ ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନଃ (ସହାର୍ଥ ବହୁବ୍ରୀହିଃ) । ଭୂପତିନା = ଭୁବ ପତିଃ, ତେନ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ରମାଳାଲୋଭେନ = ରସ୍ୟ ମାଳା (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ), ତସ୍ୟା ଲୋଭଃ, ତେନ (ସପ୍ତମୀ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । କଳତ୍ରଭୃତି = କଳରଂ ଚ ଭୃତ୍ୟ ଚ, ତେ (ଦ୍ବନ୍ଦ୍ବ) । ସ୍ମୋସଙ୍ଗ = ସ୍ୱସ୍ୟ ଉତ୍ସଙ୍ଗ ( ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – କିଂ, ସତ୍ୟ, ଏତତ୍, ସରଃ, କପି, ଏଷ, ନୃପତିଃ, ଅହଂ, ସପରିଜନଃ, ପ୍ରଭୃତା, ରମାଳା, ବାନରଃ, ସର୍ବେ, କଳତ୍ରଭୃତ୍ୟା = କର୍ଭରି ୧ ମା । ଭୋ !, ଯୂଥାଧୂପ !, ସ୍ବାମିନ୍ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ବାନରଃ = ଅପି ଅବ୍ୟୟ ଯୋଗେ ୧ମା । ସ୍ୱ, ବାନରଃ, ସ୍ଵସ୍ଵଭଙ୍ଗ, ଆରୋପିତଃ = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧ ମା । ଭୂଭୁଜା, ରାଜ୍ଞା = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । ପ୍ରତ୍ୟକ୍ଷତୟା, ମତ୍କଣ୍ଠସ୍ଥିତୟା, ରନ୍ମାଳୟା, ରନ୍ମାଳାଲୋଭେନ, ଦୋଳାଧ୍ଵରୂଢ଼େନ, ଯେନ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ସୁଖେନ = ପ୍ରକୃତ୍ୟାଦିତ୍ୟ ଉପସଂଖ୍ୟାନମ୍ ଯୋଗେ ୩ୟା । ମୟା, ଭୂପତିନା = ସହ ଯୋଗେ ୩ୟା । ଅନୁଷ୍ଠିତେ = ଭାବେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତି ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ଆକର୍ୟ୍ଯ = ଆ + କର୍ଣ୍ଣ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ସମାହୂତଃ = ସମ୍ + ଆ + ହେ + କ୍ତ । ପୃଷ୍ଟୀ = ପ୍ରଚ୍ଛ + କ୍ତ । ସତ୍ୟମ୍ = ସତ୍ + ଯତ୍ । ଶୁଦ୍ଧା = ଶୁ + ସ୍କାଚ୍ । ଲୋଭଃ = ଲୁଭ୍ + ଘଞ୍ଚେ । ପ୍ରସ୍ଥିତଃ = ପ୍ର + ସ୍ଥା + କ୍ତ ।

Text – 19

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

तृष्णे देवि नमस्तुभ्यं यया वित्तान्विता अपि।

अकृत्येषु नियोज्यन्ते भ्राम्यन्ते दुर्गमेष्वपि ॥ ८ ॥

ତୃଷେ ଦେବି ନମସ୍ତୁଭ୍ୟ ଯୟା ବିଭାନ୍ବିତା ଅପି ।

ଅକୃତ୍ୟେଷୁ ନିୟୋଜ୍ୟନ୍ତେ ଭ୍ରାମ୍ୟନ୍ତେ ଦୁର୍ଗମେଶ୍ୱପି ॥ ୮॥

ଅନ୍ବୟ – ତୃଷେ ଦେବି ! ତୁଭ୍ୟ ନମଃ । ବିଭାନ୍ବିତା ଅପି ଯୟା ଅକୃତ୍ୟେଷୁ ନିୟୋଜ୍ୟନ୍ତେ ଦୁର୍ଗମେଷୁ ଅପି ଭ୍ରାମ୍ୟନ୍ତେ ।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ତୁଭ୍ୟମ୍ = ତୁମକୁ । ବିଭାନ୍ବିତା = ଧନବନ୍ତ ଲୋକମାନେ । ଅପି = ମଧ୍ୟ । ଯୟା = ଯାହାଦ୍ୱାରା । ଅକୃତ୍ୟେଷୁ = ଅକରଣୀୟ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟରେ । ନିୟୋଜ୍ୟନ୍ତେ = ନିଯୁକ୍ତ ହୋଇଥା’ନ୍ତି । ଦୁର୍ଗମେଷୁ = ଦୁର୍ଗମ ସ୍ଥାନରେ । ଗ୍ରାମ୍ୟନ୍ତେ = ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିଥା’ନ୍ତି ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ହେ ତୃଷ୍ଣାଦେବି ! ତୁମକୁ ନମସ୍କାର । ଯାହାଙ୍କଦ୍ୱାରା ଧନ୍ତବନ୍ତ ଲୋକମାନେ ମଧ୍ୟ ଅକରଣୀୟ କାର୍ଯ୍ୟରେ ନିୟୋଜିତ ହୋଇଥା’ନ୍ତି ଓ ଦୁର୍ଗମ ସ୍ଥାନରେ ମଧ୍ୟ ଭ୍ରମଣ କରିଥା’ନ୍ତି ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ନମସ୍ତୁଭ୍ୟମ୍ = ନମଃ + ତୁଭ୍ୟମ୍ । ବିଭାନ୍ବିତା = ବିତ୍ତ + ଅନ୍ବିତା । ଦୁର୍ଗମେଷ୍ଠପି = ଦୁର୍ଗମେଷୁ + ଅପି ।

ସମାସ – ବିଭାନ୍ବିତଃ = ବିଭେନ ଅଦ୍ଵିତଃ, ତେ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ଅକୃତ୍ୟେଷୁ = କୃତ୍ୟ, ତେଷୁ (ନଞ୍ଜ୍ ତପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ବିଭାନ୍ବିତା = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧ମା । ତୃଷେ, ଦେବି ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ତୁଭ୍ୟମ୍ = ନମଃ ଯୋଗେ ୪ର୍ଥୀ । ଅକୃତ୍ୟେଷୁ, ଦୁର୍ଗମେଷୁ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

Text – 20

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

तथाच – इच्छति शती सहस्रं सहस्री लक्षमीहते।

लक्षाधिपस्तथा राज्यं राज्यस्थः स्वर्गमीहते ॥ ९ ॥

ତଥା ଚ – ଇଚ୍ଛତି ଶତୀ ସହସ୍ର ସହସ୍ତୀ ଲକ୍ଷମୀହତେ ।

ଲକ୍ଷାଧୂପସ୍ତଥା ରାଜ୍ୟ ରାଜ୍ୟସ୍ଥ ସ୍ୱର୍ଗମୀହତେ ॥ ୯ ॥

ଅନ୍ୱୟ – ଶତୀ ସହସ୍ର ଇଚ୍ଛତି, ସହସ୍ତୀ ଲକ୍ଷମ୍ ଈହତେ ତଥା ଲକ୍ଷାଧୂପଃ ରାଜ୍ୟ (ଈହତେ), ରାଜ୍ୟସ୍ଥ ସ୍ବର୍ଗମ୍ ଈହତେ । ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଶତୀ = ଶତମୁଦ୍ରାର ଅଧିକାରୀ । ସହସ୍ରମ୍ = ହଜାରକୁ । ଇଚ୍ଛତି = ଇଚ୍ଛାକରେ । ଈହତେ = ଇଚ୍ଛାକରେ । ରାଜ୍ୟସ୍ଥ = ରାଜପଦରେ ପ୍ରତିଷ୍ଠିତ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ସେହିପରି – ଯେ ଶତମୁଦ୍ରାର ଅଧିକାରୀ, ସେ ସହସ୍ର ପାଇବାକୁ ଇଚ୍ଛାକରେ, ‘ଯାହାର ସହସ୍ର ମୁଦ୍ରା ଅଛି ସେ ଲକ୍ଷମୁଦ୍ରା କାମନା କରୁଅଛି । ପୁନଶ୍ଚ ଯେ ଲକ୍ଷାଧୂପତି ସେ ରାଜ୍ୟ ଅଭିଳାଷ କରୁଅଛି ଓ ଯେ ରାଜପଦରେ ପ୍ରତିଷ୍ଠିତ ହୋଇଅଛି ସେ ସ୍ୱର୍ଗକାମନା କରୁଅଛି ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ଲକ୍ଷମିଚ୍ଛତି = ଲକ୍ଷମ୍ + ଇଚ୍ଛତି । ଲକ୍ଷାଧ୍ଵସ୍ତଥା = ଲକ୍ଷାଧୂପଃ + ତଥା । ସ୍ୱର୍ଗମୀହତେ = ସ୍ବର୍ଗମ୍ + ଈହତେ ।

ସମାସ – ଶତୀ = ଶତମ୍ ଇଚ୍ଛତି ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ସହସ୍ତୀ = ସହସ୍ରମ୍ ଇଚ୍ଛତି ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ ) । ରାଜ୍ୟସ୍ଥ = ରାଜ୍ୟ ତିଷ୍ଠତି ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ଶତୀ, ସହସ୍ତୀ, ଲକ୍ଷାଧୂପ, ରାଜ୍ୟସ୍ଥ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ସହସ୍ର, ଲକ୍ଷମଂ, ରାଜ୍ୟ, ସ୍ଵର୍ଗମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା ।

Text – 21

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

तथा च- जीर्य्यन्ते जीर्य्यतः केशा दन्ता जीर्य्यन्ति जीर्य्यतः ।

जीर्य्यतश्चक्षुषी श्रोत्रे तृष्णेका तरुणायते ॥ १० ॥

ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତେ ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ କେଶ ଦନ୍ତା ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ ।

ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଣ୍ଢ କ୍ଷୁଷୀ ଶ୍ରୋତ୍ରେ ତୃଷ୍ଣିକା ତରୁଣାୟତେ ॥ ୧୦ ||

ଅନ୍ବୟ – ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ କେଶା ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତେ, ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ ଦନ୍ତା ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ । କୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ ଚକ୍ଷୁଷୀ (ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତେ) (ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ) ଶ୍ରୋତ୍ରେ (କୀର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତି) । ଏକା ତ୍ରିଷ୍ଣା ତରୁଣାୟତେ ।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – କୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ = ଜରାକ୍ରାନ୍ତ ବ୍ୟକ୍ତିର । କୀର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତେ = ଶୁକ୍ଳ ହୋଇଯାଏ । ତରୁଣାୟତେ ତରୁଣ ହୋଇଥାଏ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଜରାକ୍ରାନ୍ତ ବ୍ୟକ୍ତିର କେଶ ଶୁକ୍ଳ ହୋଇଯାଏ, ଦନ୍ତଗୁଡ଼ିକ ଝଡ଼ିପଡ଼ନ୍ତି, ଚକ୍ଷୁ ଦୃଷ୍ଟିଶକ୍ତି ହରାଏ, କର୍ଷ ଶୁଣିପାରେ ନାହିଁ, କିନ୍ତୁ କେବଳ ତୃଷ୍ଣା ହିଁ ତରୁଣ ହୋଇଥାଏ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଶ୍ଚକ୍ଷୁଷୀ = ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ + ଚକ୍ଷୁଷୀ । ତୃଷ୍ଣିକା = ତୃଷ୍ଣା + ଏକା ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – କେଶଃ, ଦନ୍ତା, ଏକା, ତୃଷ୍ଣା = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ଜୀର୍ଯ୍ୟତଃ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ଚକ୍ଷୁଷୀ, ଶ୍ରୋତ୍ରେ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

Text – 22

अथ तत्सरः ………………………………….. दर्शयामि।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ଅଥ = ଏହାପରେ । ସମାସାଦ୍ୟ = ନିକଟରେ ପହଞ୍ଚି । ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୁଷ = ପ୍ରଭାତ । ଉବାଚ = କହିଲା । ଅପି = ମଧ୍ୟ । ଏବ = ହିଁ । ଯେନ = ଯଦ୍ବାରା । ଆସାଦ୍ୟ = ପାଇ । ପ୍ରଭୂତଃ = ପ୍ରଚୁର ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏହାପରେ ସେହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀ ନିକଟରେ ପହଞ୍ଚି ବାନର ପ୍ରଭାତ ସମୟରେ ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ କହିଲା । ହେ ମହାରାଜ ! ଏଠାରେ ଅଧେ ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋଦୟ ହେଲାବେଳକୁ ଯେଉଁମାନେ ଏହି ପୁଷ୍କରିଣୀରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତି, ସେମାନେ ସିଦ୍ଧିଲାଭ କରନ୍ତି । ତେଣୁ ସମସ୍ତ ଲୋକ ଏକାଠି ହିଁ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରନ୍ତୁ, ପୁନଶ୍ଚ ତୁମେ ମୋ ସହିତ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିବ, ତାହାହେଲେ ମୁଁ ଆପଣଙ୍କୁ ପୂର୍ବଦୃଷ୍ଟ ସ୍ଥାନକୁ ନେଇ ପ୍ରଚୁର ରତ୍ନମାଳା ଦେଖାଇଦେବି ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ସମାସାଦ୍ୟ = ସମ୍ + ଆସାଦ୍ୟ । ରାଜାନମୁବାଚ = ରାଜାନମ୍ + ଉବାଚ । ଅର୍ଥୋଦିତେ = ଅର୍ଷ + ଉଦିତେ । ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟତ୍ର = ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟୋ + ଅତ୍ର । ସିଦ୍ଧିର୍ଭବତି = ସିଦ୍ଧି + ଭବତି । ସର୍ବୋଽପି = ସର୍ବ + ଅପି । ଏକଦୈବ = ଏକଦା + ଏବ । ପୁନର୍ମୟା = ପୁନଃ + ମୟା । ପ୍ରଭୃତ୍ୟସ୍ତେ = ପ୍ରଭୂତଃ + ତେ ।

ସମାସ – ପୂର୍ବଦୃଷ୍ଟ = ପୂର୍ବ ଦୃଷ୍ଟ (କର୍ମଧାରୟ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ସରଃ, ବାନରଃ, ସିଦ୍ଧା, ଜନଃ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ଦେବ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ସର୍ବ = ଅପି ଅବ୍ୟୟ ଯୋଗେ ୧ମା । ରାଜାନମ୍, ସ୍ଥାନମ୍, ରତ୍ନମାଳା = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ଯେନ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା । ତୃୟା = ଅନୁକ୍ତ କର୍ଜରି ୩ୟା । ମୟା = ସହ ଯୋଗେ ୩ୟା । ତେ = ସଂପ୍ରଦାନେ ୪ର୍ଥୀ । ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟାନାମ୍ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୁଷସମୟେ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ । ଅର୍ଥୋଦିତେ, ସୂର୍ଯ୍ୟ = ଭାବେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ସମାସାଦ୍ୟ = ସମ୍ + ଆ + ସଦ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ସିଦ୍ଧି = ସିଧ୍ + ଭିନ୍ । ପ୍ରବେଷ୍ଟବ୍ୟମ୍ = ପ୍ର + ବିଶ୍ + ତବ୍ୟମ୍ । ଦୃଷ୍ଟି = ଦୃଶ୍ + କ୍ତ । ସ୍ଥାନମ୍ = ସ୍ଥା + ଲୁଟ୍ ।

Text – 23

अथ प्रबिष्टास्तेः ………………………… नात्र प्रवेशितः।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ତଚ୍ଛତ୍ମା = ତାହା ଶୁଣି । ସତୁରମ୍ = ଶୀଘ୍ର । ଆରୁହ୍ୟ = ଚଢ଼ି । ପରିଜନଃ = ପରିବାର ଲୋକେ, ଆତ୍ମୀୟ ଜନ । ବୈରମ୍ = ଶତ୍ରୁ । ମତ୍ସ୍ୟ = ମନେକରି ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ଏହାପରେ (ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ) ପ୍ରବେଶ କରିଥିବା ସେହି ସମସ୍ତ ଲୋକମାନଙ୍କୁ ରାକ୍ଷସ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କଲା । ଏହାପରେ ବହୁସମୟ ପର୍ଯ୍ୟନ୍ତ ସେମାନେ ନ ଫେରିବାରୁ ରାଜା ବାନରକୁ କହିଲେ– ଆହେ ଦଳପତି ! ମୋର ଲୋକମାନେ ଏତେ ବିଳମ୍ବ କରୁଛନ୍ତି କାହିଁକି ? ତାହା ଶୁଣି ବାନର ଅତିଶୀଘ୍ର ଗଛକୁ ଚଢ଼ିଯାଇ ରାଜାଙ୍କୁ କହିଲା– ଆହେ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ରାଜା ! ରାକ୍ଷସ ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ତୁମର ସମସ୍ତ ପରିଜନଙ୍କୁ ଭକ୍ଷଣ କରିଛି, କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଜନିତ ଶତ୍ରୁତା ମୋଦ୍ଵାରା ସାଧୁତ ହୋଇଛି । ତେଣୁ ଏବେ ଯାଅ । ତୁମେ ମୋର ପ୍ରଭୁ ଅଟ ବୋଲି ତୁମକୁ ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରେ ପ୍ରବେଶ କରାଇଲି ନାହିଁ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟାସ୍ତେ = ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟା + ତେ । ବାନରମାହ = ବାନରମ୍ + ଆହ । ପୃଥାଧୂପ = ଯୂଥ + ଅଧୂପ । କିମିତି = କିମ୍ + ଇତି । ତଚ୍ଛତ୍ମା = ତତ୍ + ଶୁଦ୍ଧା । ବୃକ୍ଷମାରୁହ୍ୟ = ବୃକ୍ଷମ୍ + ଆରୁହ୍ୟ । ରାଜାନମୁବାଚ = ରାଜାନମ୍ + ଉବାଚ । ରାକ୍ଷସେନାରଃ = ରାକ୍ଷସେନ + ଅନ୍ତଃ । ଋକ୍ଷିତସ୍ତେ = ଊକ୍ଷିତଃ + ତେ । ତଦ୍ଗମ୍ୟତାମ୍ = ତତ୍ + ଗମ୍ୟତାମ୍ । ସ୍ଵାମୀତି = ସ୍ଵାମୀ + ଇତି । ନାତ୍ର = ନ + ଅତ୍ର ।

ସମାସ – ନରପତେ ! = ନରାନାଂ ପତିଃ, ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ( ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଜମ୍ = କୁଳସ୍ୟ କ୍ଷୟଂ (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ତସ୍ମିନ୍ ଜାୟତେ ଇତି (ଉପପଦ ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ରାଜା, ଜନଃ, ବାନରଃ, ତ୍ଵମ୍ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । ତେ, ଲୋକା, ସର୍ବେ, ପରିଜନଃ, କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଜମ୍, ବୈରମ୍ = ଉଲ୍ଲେ କର୍ମଣି ୧ ମା । ଭୋ ଯୂଥାଧୂପ !, ଭୋ ଦୁଷ୍ଟନରପତେ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ବାନରମ୍, ବୃକ୍ଷମ୍, ରାଜାନମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ସତ୍ଵରମ୍ = କ୍ରିୟା ବିଶେଷଣେ ୨ୟା । ରାକ୍ଷସେନ, ସଲିଳସ୍ଥିତେନ, ମୟା = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । ମେ = ସମ୍ବନ୍ଧ ୬ଷ୍ଠୀ । ତେଷୁ, ଚିରାୟମାଶେଷୁ = ଭାବେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ପ୍ରବିଷ୍ଟ = ପ୍ର + ବିଶ୍ + କ୍ତ । ଶୁଦ୍ଧା = ଶୁ + କ୍ଳାଚ୍ । ଆରୁନ୍ୟ = ଆ + ରୁହ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଦୁଷ୍ + କ୍ତ । ସାଧୁମ୍ = ସାଧ୍ + ଣିଚ୍ + କ୍ତ । ମତ୍ସ୍ୟ = ମନ୍ + ସ୍କାଚ୍ ।

Text – 24

ଶ୍ଳୋକ :

उक्तं च-

कृते प्रतिकृतिं कुर्य्यात् हिंसिते प्रतिहिंसितम्।

न तत्र दोषं पश्यामि दुष्टे दुष्टं समाचरेत् ॥ ११ ॥

କୃତେ ପ୍ରତିକୃତଂ କୁର୍ଯ୍ୟାତ୍ ହିଂସିତେ ପ୍ରତିହିଂସିତମ୍ ।

ନ ତତ୍ର ଦୋଷ ପଶ୍ୟାମି ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ସମାଚରେତ୍ || ୧୧ ||

ଅନ୍ବୟ – କୃତେ ପ୍ରତିକୃତଂ କୁର୍ଯ୍ୟାତ୍ ହିଂସିତେ ପ୍ରତିହିଂସିତଂ (କୁର୍ଯ୍ୟାତ୍) । ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ସମାଚରେତ୍ ତତ୍ର ଦୋଷ ନ ପଶ୍ୟାମି ।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – କୃତେ = ଉପକାରରେ । ପ୍ରତିକୃତିମ୍ = ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୁପକାର । କୁର୍ଯ୍ୟାତ୍ = କରିବା ଉଚିତ । ସମାଚରେତ୍ = ସମ୍ୟକ୍ ଆଚରଣ କରିବା ଉଚିତ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – କେହି ଉପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ୟୁପକାର ଓ ଅପକାର କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତ୍ୟପକାର କରିବା ଉଚିତ, କେହି ହିଂସା କଲେ ତା’ର ପ୍ରତିହିଂସା କରିବା ଉଚିତ । ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ସହିତ ଦୁଷ୍ଟ ଆଚରଣ କରିବା ଉଚିତ । ଏଥିରେ (ମୁଁ) କୌଣସି ଦୋଷ ଦେଖୁନାହିଁ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ଦୁଷ୍ଟ, ପ୍ରତିକୃତି, ପ୍ରତିହିଂସିତାଂ, ଦୋଷମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । କୃତେ, ହିଂସିତେ, ଦୁଷ୍ଟ = ଅଧିକରଣେ ୭ମୀ ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – କୃତିମ୍ = କୃ + ସ୍କ୍ରିନ୍ । ଦୋଷମ୍ = ଦୁଷ୍ + ଘଞ୍ଜ୍ । ଦୁଷ୍ଟମ୍ = ଦୁଷ୍ + କ୍ତ ।

Text – 25

तत्त्वया ……………………………. सानन्दमिदमाह-

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – କୁଳକ୍ଷୟଃ = ବଂଶନାଶ । ପୁନଃ = ପୁଣି । ଆକର୍ୟ୍ଯ = ଶୁଣି । ଶୋକାବିଷ୍ଟ = ମନଦୁଃଖରେ । ଯଥାଯାତମାର୍ଗେଣ = ଯେଉଁ ବାଟରେ ଯାଇଥିଲେ । ନିଷ୍ଠାନ୍ତଃ = ଫେରିଲେ । ତୃପ୍ତ = ଆନନ୍ଦିତ ହେଲା । ନିଷ୍କ୍ରମ = ବାହାରି । ସାନନ୍ଦମ୍ = ଆନନ୍ଦର ସହିତ । ଆହ = କହିଲା ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ତୁ ମୋର ବଂଶନାଶ କରିଥିଲୁ, ମୁଁ ସେହିପରି ତୋର ବଂଶନାଶ କଲି । ଏହା ଶୁଣି ରାଜା କୋପାବିଷ୍ଟ ହୋଇ ପାଦରେ ଚାଲି ଚାଲି ଯେଉଁ ମାର୍ଗରେ ଆସିଥିଲେ ସେହି ମାର୍ଗରେ ଫେରିଗଲେ । ରାଜା ଚାଲିଯିବା ପରେ ରାକ୍ଷସ ତୃପ୍ତ ହୋଇ ଜଳ ମଧ୍ୟରୁ ବାହାରି ଆନନ୍ଦରେ କହିଲା –

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ପୁନସ୍ତବେତି = ପୁନଃ + ତବ + ଇତି । ଅଥୈତଦାକର୍ୟ୍ଯ = ଅଥ + ଏତତ୍ + ଆକର୍ଯ୍ୟ । ଶୋକାବିଷ୍ଟ = ଶୋକ + ଆଦିଷ୍ଟ । ପଦାତିରେକାକୀ = ପଦାତିଃ + ଏକାକୀ। ରାକ୍ଷସପ୍ତା = ରାକ୍ଷତଃ + ତୃପ୍ତ । ଜଳାନିଷ୍କ୍ରମ୍ୟ ଜଳାତ୍ + ନିଷ୍କ୍ରମ । ସାନନ୍ଦମିଦମାହ = ସାନନ୍ଦମ୍ + ଇଦମ୍ + ଆହ ।

ସମାସ – କୁଳକ୍ଷୟୀ = କୁଳସ୍ୟ କ୍ଷୟଃ ( ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) । ଶୋକାବିଷ୍ଟ = ଶୋକେନ ଆବିଷ୍ଟୀ (ତୃତୀୟା ତତ୍ତ୍ଵପୁରୁଷ) । ସାନନ୍ଦମ୍ = ଆନନ୍ଦେନ ସହ ବର୍ତ୍ତମାନମ୍ ( ସହାର୍ଥ ବହୁବ୍ରୀହିଃ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ରାଜା, ଶୋକାବିଷ୍ଟ, ପଦାତିଃ, ଏକାକୀ, ରାକ୍ଷସ = କଉଁରି ୧ ମା । କୁଳକ୍ଷୟ = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧ମା । ତୃୟା, ମୟା = ଅନୁସ୍ତେ କଉଁରି ୩ୟା । ମାର୍ଗଣ = ମାର୍ଗବାଚକ ଶବ୍ଦଯୋଗେ ୩ୟା । ଜଳାତ୍ = ଅପାଦାନେ ୫ମୀ । ତସ୍ମିନ୍, ଭୂପତୌ, ଗତେ = ଭାବେ ୭ମୀ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – କୃତଃ = କୃ + କ୍ତ । ଆକର୍ୟ୍ଯ = ଆ + କର୍ଣ୍ଣ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ । ଆବିଷ୍ଟ = ଆ + ବିଶ୍ + କ୍ତ । ନିଦ୍ରାତଃ = ନିଃ + କ୍ରମ୍ + କ୍ତ । ତୃପ୍ତ = ତୃପ୍ + କ୍ତ । ନିଷ୍କ୍ରମ୍ୟ = ନିଃ + କ୍ରମ୍ + ଲ୍ୟାପ୍ ।

Text – 26

हतः शत्रुः कृतं मित्रं रत्नमाला न हारिता ।

नानास्वादितं तोयं साधु भो बटवानर ! ॥ १२ ॥

ହତଃ ଶତ୍ରୁ କୃତଂ ମିରଂ ରତ୍ନମାଳା ନ ହାରିତା ।

ନାଳେନାସ୍ୱାଦିତଂ ତୋୟଂ ସାଧୁ ଭୋ ବଟବାନର ! ॥ ୧୨ ॥

ଅନ୍ୱୟ – ଭୋ ବଟବାନର ! ସାଧୁ, ନାଳେନ ତୋୟମ୍ ଆସ୍ବାଦିତଂ, ଶତଃ ହତଃ, ମିତ୍ର କୃତମ୍, ରତ୍ନମାଳା ନ ହାରିତା (ଚ୍ଚ)।

ଶବ୍ଦାର୍ଥ – ସାଧୁ = ଉତ୍ତମ ବା ଧନ୍ୟ । ନାଳେନ = ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ଦ୍ଵାରା । ତୋୟମ୍ = ଜଳ । ଆସ୍ଵାଦିତମ୍ = ପିଇଅଛି । ହତଃ = ମରାଯାଇଛି । ନ ହାରିତା = ହରାଇ ନାହିଁ ।

ଅନୁବାଦ – ହେ ବାନର ତୁମେ ଧନ୍ୟ ! ପଦ୍ମନାଡ଼ ସାହାଯ୍ୟରେ ଜଳ ପିଇ ତୁମ ଶତ୍ରୁକୁ ବିନାଶ କରିଅଛ । ମୋତେ ମିତ୍ର କରିପାରିଛି ଓ ରତ୍ନମାଳାକୁ ମଧ୍ଯ ହରାଇ ନାହଁ ।

ବ୍ୟାକରଣ

ସନ୍ଧିବିଚ୍ଛେଦ – ନାଳେନାସ୍ୱାଦିତମ୍ = ନାଜେନାସ୍ୱାଦିତମ୍ = ନାଳେନ + ଆସ୍ଵାଦିତମ୍ ।

ସମାସ – ରତ୍ନମାଳା = ରତ୍ନସ୍ୟ ମାଳା (ଷଷ୍ଠୀ ତତ୍ପୁରୁଷ) ।

ସକାରଣବିଭକ୍ତି – ଭୋ ବଟବାନର ! , ସାଧୁ ! = ସମ୍ବୋଧନେ ୧ମା । ଶତ୍ରୁ, ମିତ୍ର, ରତ୍ନମାଳା = ଉକ୍ତ କର୍ମଣି ୧ ମା । ଆସ୍ଵାଦିତଂ, ତୋୟମ୍ = କର୍ମଣି ୨ୟା । ନାଜେନ = କରଣେ ୩ୟା ।

ପ୍ରକୃତିପ୍ରତ୍ୟୟ – ହତଃ = ହନ୍ + କ୍ତ । କୃତମ୍ = କୃ + କ୍ତ । ହାରିତା = ଦୃ + ଣିଚ୍ + କ୍ତ + ଟାପ୍ ।

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()